If you’re a parent or grandparent, you may know of the “Choose Your Own Adventure” storybook series. Written in second person, they make “you” the hero. The reader makes choices as the story unfolds, leading to one of several possible endings.

That format is disturbingly similar to a lot of economic forecasting. The economist—who of course envisions himself a hero (don’t we all, at least privately?)—chooses models or datasets that lead to places potentially quite different from those who make other choices. The differences grow wider as the stories unfold. The endings, while unique to each economist, are satisfying because they always reflect those initial choices. There’s no right or wrong ending… just the one you created.

Except…

The economy isn’t a storybook. It’s the real world and it affects everyone. Its direction depends in part on the policy choices of central bankers and government leaders. To make good choices, they need to know with reasonable confidence what proposed policies will do.

In other words, they need accurate economic forecasts. Economists aren’t very good at delivering those. But economists are very good at creating models which central bankers, government bureaucrats, and politicians prefer. Longtime readers know I believe that today’s economists serve the same function once performed by astrologers or shamans. Rather than looking at sheep entrails and telling the king what he wants to hear, they prefer the far more “scientific” method of selectively choosing data which has the wonderful ability to tell a politician his preferred policy is correct.

Do you want a model that tells you we need to raise taxes? Carefully select the correct data and your models will reflect that policy choice. You think we should cut taxes? Easy to create a model for that. Spend more on your preferred government program? Or eliminate one you dislike? Simply choose the correct data and your model will confirm your sponsor’s wisdom.

Many economists have physics envy. They want to model the economy in all its complexity, which in fact is a statistical impossibility. Every forecast (even and maybe especially mine!) should be taken with a grain of salt. And with some economists you’ll need the whole saltshaker. Maybe more than one…

And recent experience says the profession’s forecasting skills are getting worse, not better. Today we’ll talk about why this is such a problem and what, if anything, we can do about it.

Before going further, I want to be clear: Forecasting is hard. Everyone who tries to do it, no matter how thorough and sincere, makes mistakes. Economies are incredibly complex systems. To at least some degree, their direction seems purely random. Adam Smith referred to “the invisible hand” at a time when the world economy was far simpler than today’s.

And then we get unpredictable, unprecedented events which seemingly happen all the time and can change everything.

We should also note “the economy” is a misnomer. We have a bunch of different individual economies whose condition can vary wildly. You can be doing well while the national averages say the country is in recession. Or you can lose your job and go bankrupt while “the economy” is booming. It's like the old joke that says when your neighbor loses his job it's a recession. When you lose your job it's a depression.

No forecast can accurately capture everyone’s individual experience or prospects. At best, they can describe broad tendencies. And in large countries, “broad” can hide a lot of variation.

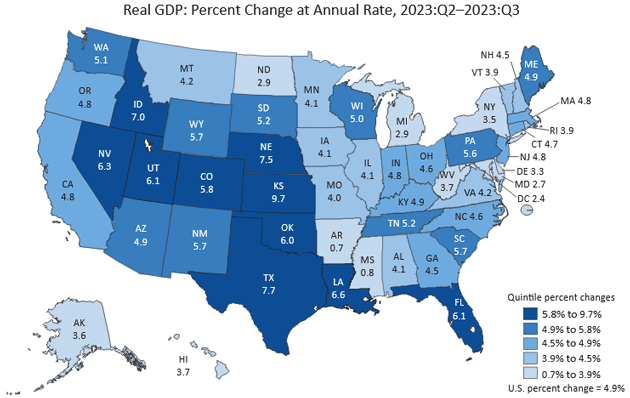

Even a forecast that nails the national picture can still have little practical bearing on your personal and regional situation. In Q3 of 2023, US real GDP grew at a 4.9% annual rate, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. BEA also breaks this down by state. Growth in that same quarter ranged from 9.7% in Kansas down to 0.7% in Arkansas. Note that there is no simple heuristic that can explain the differences. It’s not a red state/blue state thing. It is not coastal versus flyover country.

Source: BEA

A forecast that predicted strong GDP growth was right in some places and dismally wrong in others. That shouldn’t surprise us; the US is a big country with a lot of regional variation. But that variation necessarily makes forecasting difficult.

The same applies to unemployment, by the way. The headline unemployment rate was 3.7% in December 2023. By state, it varied from 1.9% in Maryland and North Dakota up to 5.4% in Nevada. Whether the labor market is tight or slipping depends on where you are. The variations become even more significant when you break it down to city and county levels. A large employer in a small county can be significant.

I mention local variation because the Federal Open Market Committee includes regional Fed presidents who are supposed to represent their region’s needs. But the data can vary, further complicating the policy choices.

Then there are models. Economists—Fed, government, and private—use models to make their forecasts. They plug in variables and examine how they affect each other. Think of a spreadsheet but vastly more complex. Yet they still can’t include the giant range of important factors.

The people who design these models, because they put a lot of effort into them, naturally want to trust the output. This leads to overconfidence. That is especially true when you get a lot of economists basically trying to achieve the same outcome using the same assumptions and theoretical philosophies.

Even if you could get Austrian and Keynesian economists to agree, the models would still depend on data developed by various government and private services, which has problems. I have often written about the vagaries of measuring inflation, unemployment, GDP, manufacturing output, and on and on. Yet lacking better choices, we still use this data and actually ascribe significance to it.

At the same time, not having models isn’t necessarily better. What’s the alternative? Subjectively looking at whatever data you think is important invites “confirmation bias.” That’s when people unconsciously pay more attention to data that confirms what they already believe. It affects almost everyone and is incredibly difficult to avoid.

Much like compound interest, all this produces compounded uncertainty. The data that goes into forecasts isn’t necessarily reliable, the models that process the data into forecasts aren’t necessarily reliable, and the policymakers who look at the forecasts are subjective humans with varying and often conflicting priorities. Getting any useful policy out of this multi-layered contraption is tough.

The flaws in forecasting were illustrated in real time in just the last few years. Admittedly, COVID and all the changes surrounding it were outside the bounds of anyone’s experience. That’s one of the problems, though. Both models and subjective forecasts look at past experiences and assume the future will resemble them. That’s not necessarily a good assumption.

When inflation began rising in 2020, it was perhaps reasonable to think the various pandemic disruptions were causing transient price increases. Government spending certainly added fuel to the fire. Larry Summers made himself persona non grata for a while by saying the last round of government stimulus money would create inflation, and he was right. (I said the same thing, but I’m not Larry Summers.) The Fed delayed responding until after the February 2022 Ukraine invasion, which sparked undeniable inflation that—to models and economists—seemed likely to last a while.

The Fed responded with a tightening campaign that past experience said would probably push the economy into recession. It didn’t, unless we count those two mildly negative GDP quarters as a “technical recession.” Unemployment and consumer spending paid no attention, either.

Maybe some model somewhere predicted this, but I’m not aware of it. The far more common reaction was aggressive pessimism. My friend Ed Yardeni took his own profession to task in a recent report he called Why Were Economists So Wrong? Here’s Ed:

“Both 2022 and 2023 were years of living dangerously. Pessimism about the economic outlook was in fashion. Most commentators on the economy concluded that the high inflation problem was persistent rather than transitory and that the Fed would have no choice but to engineer a recession to bring down inflation. A few of the naysayers anticipated that this would unleash a debt crisis that would cause a severe financial calamity and a very deep economic recession.

“Now that we have survived both years without the widely anticipated financial and economic debacle, pessimism has abated. There are still a few economic prognosticators predicting a recession in 2024, but far fewer than over the past two years. So now might be a good time to draw some lessons about the economy and the financial system from the many misleading theories and models that fueled so much pessimism.”

From there Ed went into a long litany of examples—not just economists but also fund managers, wealthy investors, and CEOs predicting imminent recession and/or financial crisis. They weren’t entirely wrong; we did have that mild technical recession and some bank failures. But many expected much worse. And the data they cited at the time fully supported that view. Yet it was wrong—or at least has been so far.

For example, here’s an October 2022 headline from The Wall Street Journal.

Source: WSJ

These forecasts could not possibly have been more wrong. The “Next Year” (meaning 2023) brought neither recession nor significant job losses. Now we’re in early 2024 and still wondering when the Fed will cut rates.

The article’s text is more specific but still no better:

“The US is forecast to enter a recession in the coming 12 months as the Federal Reserve battles to bring down persistently high inflation, the economy contracts and employers cut jobs in response, according to The Wall Street Journal’s latest survey of economists.

“On average, economists put the probability of a recession in the next 12 months at 63%, up from 49% in July’s survey. It is the first time the survey pegged the probability above 50% since July 2020, in the wake of the last short but sharp recession.

“Their forecasts for 2023 are increasingly gloomy. Economists now expect gross domestic product to contract in the first two quarters of the year, a downgrade from the last quarterly survey, whereby they penciled in mild growth.

“On average, the economists now predict GDP will contract at a 0.2% annual rate in the first quarter of 2023 and shrink 0.1% in the second quarter. In July’s survey, they expected a 0.8% growth rate in the first quarter and 1% growth in the second.

“Employers are expected to respond to lower growth and weaker profits by cutting jobs in the second and third quarters. Economists believe that nonfarm payrolls will decline by 34,000 a month on average in the second quarter and 38,000 in the third quarter. According to the last survey, they expected employers to add about 65,000 jobs a month in those two quarters.”

The 66 economists in WSJ’s survey included a wide variety of backgrounds, philosophies, and methodologies, and none was remotely close to correct. They should ask themselves why.

Prior to the last few years, blue chip economists almost without fail never predicted a recession, often when we were already in one. This time they predicted recessions that didn’t happen. So far, at least, their record is still something like 0 for 300.

I’m sure these economists want to do better. The rest of us would certainly benefit from reliable forecasts, even imperfect ones. So, it’s worth asking what they missed.

Ed Yardeni listed 10 misconceptions that helped produce these poor forecasts. I’ll list some of them and add my comments.

Misconception #1: Tight monetary policies always cause recessions.

That’s how it should work. Tightening rates weakens demand by making major purchases more expensive to finance. This leads to layoffs which further reduce demand as unemployed workers cut their spending. Producers have to cut prices, bringing inflation back down.

That’s a tried-and-true formula. This time it didn’t work that way. Why not? I think the main reason is that the private sector is much less leveraged than it used to be. The economy has a lot of debt, but it’s highly concentrated in the federal government. Raising rates affects spending decisions only to the extent the higher rates affect the borrower’s cash flow. Across the economy, this was minimal except to the Treasury.

Misconception #3: Consumers are running out of excess savings.

The various COVID stimulus programs gave households a lot of money while the uncertain situation made people cautious to spend. They have been slowly working through their savings, though, and the theory was that this drawdown would reduce aggregate consumer demand, possibly causing recession.

That hasn’t happened. Yardeni says the reason is that consumers have other sources of purchasing power because the tight labor market has pushed wages higher, even after inflation. Moreover, the wage increases have been strongest for front-line service workers who have a higher propensity to spend.

At the same time, the rapidly retiring Baby Boom generation is spending more on restaurants, vacations, and healthcare. This raises demand for workers in those industries, which have to respond with yet higher wages.

Misconception #5: Inverted yield curves predict recessions.

The 3M/10Y yield curve inverted in November 2022, which historically should have meant a recession about 13 months later on average. It’s now been 15 months and a recession hasn’t started yet, nor does one appear imminent. (I know, I just jinxed us!)

My friend Campbell Harvey, who pioneered this indicator, said in a recent report (which Over My Shoulder members can read here) a soft landing is still possible if the Fed aggressively cuts rates soon. That also doesn’t seem likely, which in Dr. Harvey’s view makes recession more likely. But in any case, this cycle seems to be stretching the inversion indicator well past average. Yardeni thinks this is because the Fed has learned to rapidly launch new credit facilities in response to events like the Silicon Valley Bank failure.

Misconception #9: The rest of the world doesn’t matter much.

This hasn’t been noted as much but is important. China’s real estate woes (Evergrande, etc.) slowed the Chinese economy and, most important, reduced global energy and commodity demand. This helped dampen inflation. So the lesson there is that events outside the US can matter in both directions. The war’s outbreak sparked inflation and China’s problems reduced it. The Fed had nothing to do with either.

Now ask yourself: Could any model—or for that matter, any human brain—anticipate how all these once-reasonable assumptions would fall by the wayside at once? I don’t see how.

As we approach this decade’s midpoint and the 2030s draw near, I think we should expect more and more surprising events. The “rules” we’ve all come to think are reliable will become steadily less so. Some of these surprises may be good ones, like the “no landing at all” economy. That would be nice.

My speculation, as I’ve shared with a few friends, is that the massive government debt is forming an economic black hole. As science fiction fans know, math works differently inside a black hole. The change to a different mathematics happens at something called the “event horizon.”

I think it is possible the combination of COVID and all of its ramifications, government stimulus, and even more so government debt, has created a black hole and we are approaching an event horizon where all our past observations of the economy are losing relevance. Whether or not (to use the familiar warning) past results were ever indicative of the future, they certainly aren’t now.

At the very least, we will have to get through this period with an economic navigation system that isn’t working as well as its operators think. And it wasn’t especially reliable in the first place.

This isn’t just entertainment. People who make important decisions affecting all of us are flying blind, too. This raises the risk of policy errors with potentially giant consequences.

As I’ve said in my own annual outlook letters, forecasts matter even when they’re wrong. They guide our thinking in ways that can either help or hurt. And if I’m right about the coming cyclical crises, it will be a very bumpy ride.

San Francisco, Florida, and Cape Town

I will be spending 8 days in San Francisco, where I have an opportunity to work with a doctor in San Francisco for a series of therapies that research suggests has remarkable effects on longevity and health span. I've been watching this space for some time and finally decided to pull the trigger. It is not cheap and is time consuming, but the anecdotal evidence from people who have gone through the procedures, in addition to the actual research, convinced me to give this a shot. We will know how it works out in a few months. If it's positive, I will let you know. And vice versa.

Sometime next month I will be in Florida looking at yet another longevity drug (for the second time). And as I've written, Shane and I will be in Cape Town in June.

The entire Mauldin Economics team is getting focused on the 20th annual Strategic Investment Conference, coming up in late April. This will undoubtedly be the best conference I’ve ever done. We are still finalizing some last-minute special guests. SIC will have deep dives into AI, geopolitics, and all things economic. You won’t want to miss this. More information coming soon.

With that, it's time to hit the send button. You have a great week! And don't forget to follow me on X!

Your frustrated with forecasts analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price.

Click here to learn more.