FED BALANCE SHEET

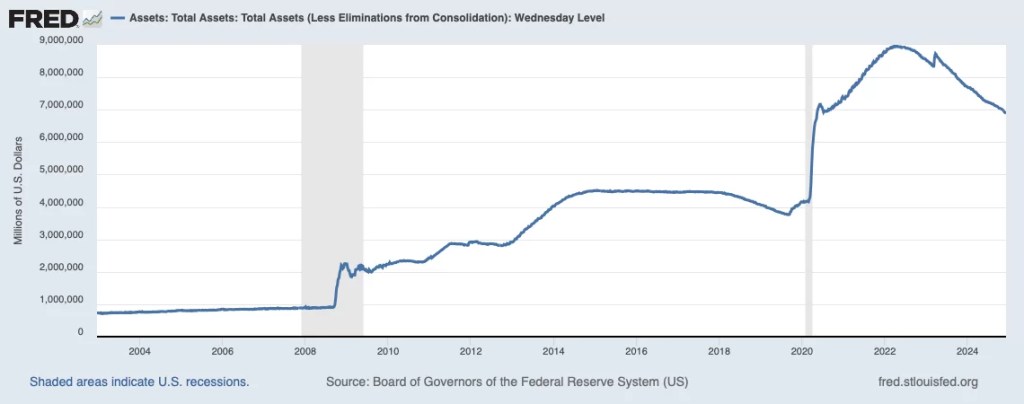

Below is a chart posted and updated regularly by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis…

As can be seen in the above chart, the total assets of the Federal Reserve Bank have declined by 22 percent since peaking in March 2022. The aforementioned peak was nearly simultaneous with the announcement by the Fed in March 2022 of a change in Fed interest rate policy.

As can be seen in the above chart, the total assets of the Federal Reserve Bank have declined by 22 percent since peaking in March 2022. The aforementioned peak was nearly simultaneous with the announcement by the Fed in March 2022 of a change in Fed interest rate policy.

Total assets include U.S. Treasury securities, debt issued by federal agencies, and mortgage-backed securities. The 22 percent decline is significant. Prior to the decline, however, the Fed’s total assets had increased more than nine-fold since 2008 from just under $1 trillion to almost $9 trillion.

An immediate Fed response to the credit crisis in 2008 was to buy up huge amounts of credit at severely discounted prices in order to stabilize a credit market that had literally collapsed. The action propelled the Fed into the prominent role of ‘buyer of last resort” and resulted in more than doubling the size of its balance sheet from less than $1 trillion to $2.25 trillion.

The increase was more astounding because it happened over three short months between September 8th and December 8th of 2008.

SOME ADDITIONAL HISTORY

After 2008, the Fed’s balance sheet continued to increase in size for the next six years, reaching $4.5 trillion before leveling off at that number for several more years. By the end of 2019, the total had dropped to $3.7 trillion.

Previously announced intentions to allow the balance to shrink in a passive way as various obligations matured were underway when the Covid-19 pandemic arrived. Government at all levels seemed to lose any vestige of common sense in their reactions to the potential health issues. A government-imposed shutdown of the economy followed by fantastically flawed financial largesse resulted in phenomenally large purchases of Treasury securities by the Federal Reserve.

From $3.7 trillion in September 2019, the Fed’s balance sheet grew to $8.7 trillion by December 2021. The peak at $8.95 trillion followed shortly.

We referred earlier to the current decline in Fed assets as significant, but that requires elaboration; or rather, putting that decline in proper context.

QUANTITATIVE TIGHTENING

“QT” or quantitative tightening, has been a relatively passive effort insofar as it pertains to shrinking the Fed’s swollen balance sheet. Rather than sell the debt securities in the open market, they are allowed to mature. The supply is simply too large and would have a negative impact on the credit markets should the Fed try to liquidate them by selling into existing markets. There may be selective opportunities to sell specific issues openly, but allowing the maturation process to unfold is a more benign way to shrink the balance sheet.

INFLATION OR DEFLATION?

Large increases in the Fed’s balance sheet are an indication of Fed actions to counter gaps in demand for Treasury securities primarily, and liquidity problems associated with credit crises in general. This is what happened in 2008 and in 2020. Looking beyond the immediate liquidity concerns, the Fed’s active purchase of debt securities in such huge quantities is inflationary.

The money advanced by the Fed to purchase debt securities which it holds on its balance sheet becomes part of the money supply and is available to lend or hold as reserves with the Fed. Once the money is lent out, it can be used again and again. Economists call this the “money-multiplier effect”. It came about because of the practice of fractional reserve banking. The turnover of the same original deposit of funds used to be somewhat limited because of the requirement that banks could lend out 90% of their deposits and must keep 10% in reserve for liquidity purposes and day-to-day demand by customers.

There is no longer a fractional reserve requirement for banks, though. The 10% reserve requirement was reduced to zero in March 2020. As a result, we now have ‘NO-RESERVE” banking. Banks are the most notoriously illiquid in modern banking history.

If the huge increases in the Fed balance sheet result in inflation, can the recent 22% decline be seen as an indication of deflation? Or, is it just non-inflationary?

FED BALANCE SHEET DECLINE IN PROPER CONTEXT

The significance of the ongoing decline in the Fed’s balance sheet might not mean much. This is especially true when consideration is given to the passive QT policy of letting credit obligations mature on their own.

Also, the Fed’s balance sheet is overwhelmingly dominated by holdings of U.S. Treasury securities which are held on the books at face value. So the recent decline is not a market-oriented drop in prices such as has been experienced in the bond market by all participants in all issues as a result of the “higher for longer” interest rate policy in effect which parallels the drop in Fed holdings on their balance sheet.

Until a few months ago, the total money supply (currency in circulation and reserve balances of member banks) had been shrinking concurrent to the decline in the Fed’s balance sheet. The decline in the money supply appears to have stopped, though; at least for now. (see Money Supply Continues To Fall, Economy Worsens – Investors Don’t Care)

Thus, we are left with a Fed balance sheet that continues to decline in size, and a money supply that is no longer shrinking – both in the face of potentially lower interest rates. It is a somewhat contradictory situation.

CONCLUSION

The sizable decline in the Fed’s balance sheet is not inflationary. An increase, though, would be inflationary, as we experienced post-2008 and post-2020.

By itself, the decline is also not deflationary. There have been no attempts to sell large quantities at a market which could trigger events and circumstances that could lead to deflation, especially if that supply were to come on the market in the current interest rate environment. This assumes there are no other extenuating circumstances that remain unknown.

The more probable explanation is that the Fed’s balance sheet continues to shrink on its own as various securities mature.

It should be noted, however, that the decline, while significant in percentage terms compared to its recent peak, still leaves the Fed balance sheet seven times larger at $6.9 trillion than in 2008 at less than $1 trillion. Compared to September 2019, shortly before the onset of the Covid pandemic, the Fed balance sheet is larger by 86 percent.

The vulnerability should not go unnoticed. Another crisis similar to 2008 or 2020 could possibly cripple the Fed. What help can you expect from the Fed when it is already burdened with staggering debt holdings prior to the beginning of another credit collapse? (also see Credit Collapse Is Deflationary)

Kelsey Williams is the author of two books: INFLATION, WHAT IT IS, WHAT IT ISN’T, AND WHO’S RESPONSIBLE FOR IT and ALL HAIL THE FED