You know I’m highly concerned about government debt in the developed world, particularly the US. I’ve said for years a crisis is coming. We’ve blown right past all our chances to avoid it. Now all we can do is imagine what the crisis will look like… and how much it will hurt.

This is necessarily speculative, and even more so because the details matter. It’s not just monetary policy that is “path dependent.” The coming crisis is also path dependent with a million ways to reach the same ugly place. And the actual details of the crisis are also unclear. Each step forward changes the available choices.

Most of the country, investors, politicians, and the general public assume that the fabled bond vigilantes us old folks talk about are really and truly dead, if they think about it at all. When the people find out that they are indeed not dead, it will be the most startling resurrection in 2,000 years.

All that said, I’m feeling a little more clarity thanks to a new report by old friend and fishing buddy Martin Barnes, longtime chief economist of The Bank Credit Analyst. Martin retired a few years ago but the new editors occasionally ask him to share his insights. His new special report, Revisiting the Debt Supercycle, describes with terrifying simplicity how this debt situation developed and where it’s going.

I first began reading the BCA in the 1990s. My late partner Gary Halbert was a fan and we pored over each month's letter. It was my first exposure to high-quality economic analysis. They were just so continually spot on. Martin, first through the letter and then through our relationship, has been one of my main mentors in my understanding of economics in general and monetary policy specifically. BCA is still part of my monthly analysis, these 30 years later. I highly recommend it.

BCA is usually reluctant to let me share or even quote their work. This report, however, is so important Martin is allowing me to excerpt portions of it in today’s letter. The full report is 17 pages so I’m still barely scratching the surface. But just this small part will give you a lot to chew on.

The Solution Created the Problem

Martin along with 1970s predecessors at BCA developed a theory they call the Debt Supercycle. The original idea was to describe how private sector debt soared in the post-World War II period. We now think of those years as a golden era, and in many ways, they were. But that time was also a key step toward our current predicament.

I’ll let Martin explain more.

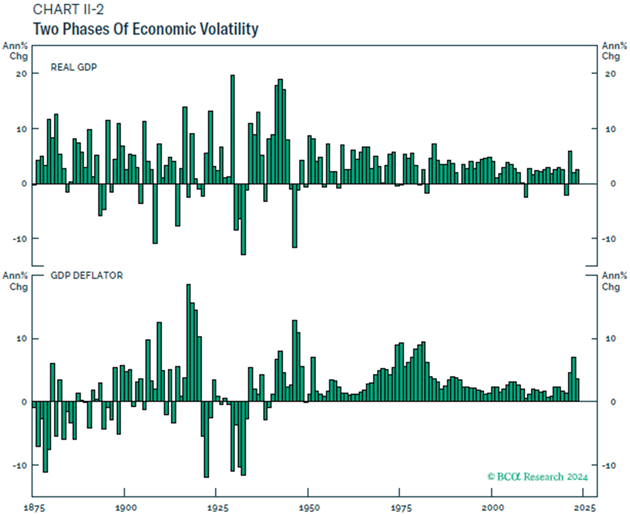

“Before going forward, we must first go back, because it is important to understand how we landed in the current situation. Chart II-2 shows 150 years of US economic history with economic growth and inflation back to 1875. One thing stands out quite clearly: Economic life was a lot more volatile in the first half of the period than in the second half. The post-WWII period has been a lot calmer on both fronts. The severe economic and financial crisis of 2007‒09 was the worst economic recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s yet it does not look like much of a downturn compared to some of the declines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Source: BCA Research

“It truly was an unfettered laissez faire economic world back then. Booms and busts in the economy and the markets tended to be violent because there was not much in the way of government interference. Human nature being what it is, the booms were associated with all kinds of excesses just as they are in modern times. However, these excesses tended to get completely washed out in the downturns. Debtors went bust, banks failed, and balance sheets were cleansed.

“Things changed dramatically after the 1930s’ Great Depression when the government decided that it could not let such a severe contraction happen again. It marked the start of government involvement to try and smooth out business cycles. Deposit insurance was created to try and prevent runs on banks, unemployment insurance provided a safety net to those who lost their jobs, and the government boosted spending on public projects. And the theories of John Maynard Keynes gave legitimacy to these policies by explaining how governments could and should use fiscal policy to counter the swings in the economy. This kind of thinking quickly became the new orthodoxy and established firm roots as the welfare state expanded.

“So far so good—it all worked very well, as highlighted by the more stable pattern of growth. After WWII, the economy no longer suffered frequent collapses—there were recessions of course, but not mini-depressions. However, there was a problem.

“As noted earlier, in the old days, the excesses built up during booms were washed out during the downturns. This meant that each new upturn began with relatively clean balance sheets. That no longer happened once governments intervened to smooth out business cycles. The excesses built up as usual but did not get fully cleansed in the recessions. Thus, each upturn began with debt and imbalances higher than in the previous cycle, and so began the steady rise in private sector indebtedness. Moreover, governments did not follow Keynes’s recommendation to run budget surpluses during good times in order to fund deficits during recessions. Instead, government deficits became the norm, regardless of the economy’s condition.”

John here again. It’s important not to sugarcoat the past as somehow ideal. Before modern central banks, the economy resolved imbalances with financial panics, bank runs, and depressions. The Fed and other institutions like the FDIC were founded to soften these wild swings, and they succeeded. But it’s now clear this stability has a cost. In trying to smooth the cycle with ever easier monetary conditions, the “solutions” allowed enormously destabilizing debt to build. Now the bill is coming due.

Macroeconomic charts typically separate debt into three categories: household debt, corporate debt, and government debt. Historically, problems usually began with excess household debt. The Great Financial Crisis of 2007‒2009 marked an important yet under-noticed shift in this balance. Here’s Martin again.

“Consumers took on an extraordinary amount of mortgage debt between 2000 and 2007 on the mistaken and naive assumption that house prices would keep rising. The inevitable bust in house prices was brutal for over-indebted homeowners and over-exposed lenders. As the collateral for debt evaporated, loan delinquencies and foreclosures soared.

“The Fed responded to the crisis by slashing interest rates and pumping massive amounts of liquidity into the financial system. Yet, extraordinarily low interest rates did not persuade consumers to take on more debt. The crisis fundamentally altered consumer attitudes toward debt, much as the 1930s’ Great Depression caused a generation of householders to shun borrowing for the rest of their lives. At the same time, an inevitable tightening in lending standards constrained credit growth from the supply side.

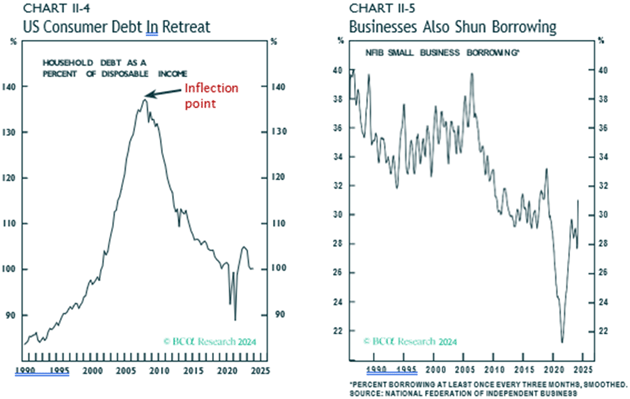

Source: BCA Research

“The failure of extreme policy reflation to encourage consumers to take on more leverage marked a critical event in the life of the Debt Supercycle. In 2014, BCA effectively pronounced the end of the Debt Supercycle in its previous form on the assumption that policy stimulus could no longer be guaranteed to encourage the private sector to take on more leverage.

“Subsequent trends have supported that thesis. The Fed kept interest rates at close to zero between 2009 and 2017 yet the ratio of household debt to income continued to decline (Chart II-4). And it has not recovered since, even though the COVID pandemic led to massive new monetary and fiscal stimulus. Corporate sector borrowing has increased as a share of income, but much of that was to finance share buybacks and mergers and acquisitions rather than to boost capital spending. The share of small businesses that borrow has continued to drop to new lows (Chart II-5).

“In sum, the data show that the Debt Supercycle in its previous form reached a major turning point 15 years ago. However, it simply transitioned from the private sector to the government sector. If consumers would not borrow and spend, then the government would step in and do it for them.”

John here. Going deeper, it’s quite insidious how what would once have been private debt is now government debt. Mortgages are probably the best example. Federal loan programs (Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, VA, etc.) either directly own or guarantee most mortgage debt. The credit risk ultimately falls on taxpayers, not the original lenders.

But that’s not all. Think about the COVID relief programs. Small businesses were allowed to use some of their Paycheck Protection Program funds for debt payments, which were then forgiven. The debt was simply transferred from the businesses to the taxpayers. Ditto for student loan forgiveness and assorted other programs.

In all these cases, the private lenders got paid, the private borrowers no longer owed those amounts, and the government’s debt grew accordingly.

We saw it again just last year in the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failures. Remember bank “deposits” are actually loans from you to the bank. The decision to pay off depositors in full including big businesses who kept accounts far above the FDIC limits was really a kind of loan forgiveness. Everyone got bailed out of what should have been losses.

In all these cases and more, large amounts of previously private debt became government debt. You can spot the point in 2009 on Martin’s chart where households began shedding debt relative to income. Much of that debt still exists; it was recategorized, not repaid.

This is a key reason government debt ballooned so much in recent years. I’ll use an ugly word here but it’s accurate: We have socialized trillions in private debt, relieving households and businesses from liability and adding it to the Treasury.

Except the private sector isn’t fully off the hook. Many who got various kinds of loan forgiveness will end up paying in other ways.

Martin went on to explain how government debt is quite different from private debt. Governments have unique powers; they can raise taxes, force financial institutions to buy government bonds, and use central banks to absorb whatever is left. They can engineer inflation and manipulate currencies. They have a big toolbox—but they can’t do magic. Limits still exist.

Here’s Martin again.

“The limit to government debt is reached when investors will no longer purchase a country’s bonds at yields that the economy can tolerate or when debt servicing costs crowd out other critical spending. There are several examples of developed economies that have hit such a debt wall such as New Zealand in the mid-1980s, Canada [and Sweden—JM] in the early 1990s and Greece in the years after 2009.

“The US clearly is not at that point yet. Long-term Treasury yields around 4% have not been high enough to significantly damage growth and interest costs, currently at 15% of federal revenues, have been manageable. However, CBO projections show that interest costs will absorb an unacceptable level of around a third of revenues by 2050…

“The bond vigilantes are well aware of US fiscal trends but have yet to take fright. Treasury yields have moved higher but that reflects tighter monetary policy, not a rise in the fiscal risk premium. This most likely will show up in a widening of spreads at the longer end of the yield curve and that has not yet happened.

“In the event of a bond-buyers strike, a crisis can be delayed by central bank bond purchases (quantitative easing), but that is not a sustainable strategy. Eventually, inflation would become a problem and it is doubtful that central bank purchases could offset a stampede out of bonds and out of the dollar if private investors completely lost confidence in government policy. There is a good chance that bond investors will lose patience if the next administration fails to restore some discipline to fiscal finances.”

That last sentence is why I am sure a crisis is coming. There is very little real chance the next administration will restore fiscal discipline, no matter how the election goes, because the American people don’t want fiscal discipline. Sure, many say they do. But that changes as soon as specific tax or spending policies enter the conversation. There’s just no constituency for reform of the scale needed to solve this. Everybody wants the other guy to have to deal with the problems of austerity. “It's not my fault we've built up this debt. It's their fault and they should suffer the consequences.” We’ve dug the hole too deep.

Could economic growth save the day? It would help, but Martin Barnes sees limits there, too. Many American consumers have decided we like our minimal-leverage lifestyles and have little interest in taking on more debt. It’s Keynes’s Paradox of Savings writ large.

“Consumers must be willing as well as able to take on more debt and that is going to be a problem. The economy and asset prices have done surprisingly well in the past year in the face of higher interest rates. Yet consumer confidence has remained muted. Inflation concerns are partly to blame but political uncertainty and geopolitical tensions may also have played a role. Public polling suggests a high percentage of Americans feel the economy is in a bad place, are concerned about government deficits and debt, and have little faith in politicians to make things better.

“Demographic trends also argue against a major new leverage cycle in the household sector. The population continues to age and younger generations do not appear to be overly interested in taking on a lot of debt. The Debt Supercycle in the private sector coincided with two important trends: the move of the Baby Boom generation into their prime earning years and a superb environment for asset prices. While asset prices have been buoyant recently, recent trends are not sustainable. Equity prices are highly valued and real home prices are far above the levels reached during the 1990s’ housing bubble.

“In sum, the conditions for the resumption of a major new leverage cycle in the household sector are not great. And it is hard to see why businesses should start to embrace more debt in an environment where future economic growth is likely to be mediocre and corporate tax rates are more likely to rise than fall.”

Martin concludes, as I do, the Debt Supercycle can only end in crisis. He thinks this crisis will bring “severe fiscal restraint.” Yet we know Americans aren’t keen on austerity… to say the least.

I was doing an interview with a financial magazine this morning, and I made the point that there will be no resolution of the government debt and deficit problem without a crisis. And I think Martin is an optimist. Interest as a percentage of government revenues will likely reach 30% by 2034 or sooner. In a budding bond crisis, interest rates will rise faster than we can imagine.

I try to imagine what kind of crisis it would take to change this, and it’s hard to see how that happens without truly massive disruptions—certainly massive protests and clashes at a minimum. Ray Dalio is now saying he sees a 40% chance of violence and civil war. None of us want that. But what are the alternatives?

Compromise on a Herculean scale is the best we can hope for. And we better hope that happens before it gets really ugly and forces a delayed compromise that will be even harder.

Anybody want to be president during that crisis?

British Columbia and NYC Inflation

I am finishing this letter in my hotel room in NYC. It has been a very productive trip meeting with my partners David Bahnsen and Brian Szytel at The Bahnsen Group. I am just so happy with what they are doing for my readers and clients. My next planned trip is late August to British Columbia where I will salmon fish with 30 of my friends and readers. And I promised to take Shane to island hop in the Caribbean later this summer.

The cost of food and everything in NYC seems up way more than 20% from a few years ago. But then again, so is Puerto Rico. I love NYC but gee whiz… Then again, the ticket to South Africa (client paid) was $16,000! I originally negotiated two tickets thinking Shane and I could stop off in Europe but that added another $30,000. Okay, it is first class, but still. We would be better off pricewise to start from PR and then to Europe. Weird.

And with that, it’s time to hit the send button. I so appreciate your comments and letters, almost as much as your time and attention. I would just remind new readers I do make a lot of tongue-in-cheek comments. Stick with me. I know my sense of humor is questionable at times. Often people don’t see the humor or think I am serious. But I never know. I gotta be me! That may be why I love longtime readers so much! They either get it or tolerate it. Have a great week!

Your needing some major back therapy after so many plane hours analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price.

Click here to learn more.