suddenly starts pawning their assets to pay for that lifestyle. Would most people take that as a sign that the celebrity's financial position is not nearly as strong as they want the world to think?

How the Federal Reserve gets the money to fund the U.S. national debt has abruptly changed in the last few weeks. The Fed has effectively "pawned" more than a trillion dollars of its most valuable assets - its ownership of U.S. Treasury obligations - through its use of reverse repurchase agreements, pledging the Treasuries as collateral to get the cash to continue to fund the federal government.

This massive pledging of assets to raise money is occurring with unprecedented size and speed. However, as explored in my prior analysis "Counterfeiters, Con Men, Mass Illusions & Funding The National Debt" (link here), many people are unable to see what is happening because they are "watching the wrong crime drama". There is a popular but mistaken belief that the Federal Reserve is using a printing press to fund the government, with the new dollars simply being printed, or created from nothing with a few electronic keystrokes.

There is indeed an enormous "crime" underway that is being veiled by a mass illusion of sorts, but to see it we need to understand how the national debt is actually funded - which is through a form of debt-based money creation. The Federal Reserve is a bank, and it gets its cash to spend - thereby creating new money - by issuing new debt. Each dollar of growth in the Federal Reserve balance sheet, each new dollar in assets (which is primarily government debt purchased by the Fed), is being financed by the Fed itself borrowing the money and taking on another new dollar in debt, another new dollar in liabilities.

That said, not all new debt is the same. At the May workshop, I warned the participants about a potentially major danger signal to look out for, which would be the Fed moving from reserves-based money creation to using reverse repos as the primary source of borrowing for new money and spending power.

That move has been in process for the last several months. Effectively pawning the Fed's massive ownership of U.S. Treasuries via reverse repos was always the place to go if the Federal Reserve ran into trouble with its usual sources of borrowing power. The Fed had previously avoided doing that for really good reasons, but the Federal Reserve has indeed gone there, on a trillion dollar scale and in a very short period of time. The warning lights are flashing brightly, for those with the eyes to see.

This analysis is part of a series of related analyses, which support a book that is in the process of being written. Some key chapters from the book and an overview of the series are linked here.

Repurchase Agreements & Reverse Repurchase Agreements

As discussed in Chapter 18 of the free book (link here), the "repo" or repurchase agreement market is a key part of the plumbing for the U.S. financial system.

"The "repo" or repurchase agreement market is not something that most individuals are familiar with - but it underpins the U.S. financial system, and is an extremely important source of cash for many banks and institutional borrowers.

A repurchase agreement is essentially a secured loan, that is legally a sale. Collateral - generally U.S. Treasury obligations - is sold to a buyer (who is effectively a lender). There is a simultaneous agreement at the time of the sale to repurchase the collateral at an agreed upon price and time, which is usually the next day. The difference in price between the sale price and the contractual repurchase price is effectively the repo rate of interest, which is generally close to the Fed Funds rate for overnight repurchase agreements.

Institutions who need cash enter in repurchase agreements with institutions who have excess cash, and this happens behind the scenes on a massive basis everyday in the U.S., and indeed it underpins the liquidity of the U.S. financial markets and the major participants. It usually works flawlessly, and the markets - and the stability of the U.S. financial system - depend on this happening."

There are always two parties to a repurchase agreement - a borrower and a lender. While they are usually just called "repos", the lender is technically entering into a repurchase agreement, which is an asset, and the borrower is entering into a reverse repurchase agreement, which is a debt. When we look at the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve (or any other financial institution), repurchase agreements are investment assets that appear on the asset side of the balance sheet, and reverse repurchase agreements are secured debts that appear on the liability side of the balance sheet.

As explored in Chapter 18, there was a financial crisis of sorts underway in the institutional markets during the fall and winter of 2019, even before the pandemic crisis hit in early 2020. Essentially, the Federal government had been pulling so much money out of the markets in order to fund the national debt, that a cash crunch developed, and repo interest rates spiked upwards, due to a lack of investors.

The Federal Reserve intervened as a lender, using its powers of reserves-based monetary creation to raise the cash to buy repurchase agreements. In other words, the Fed borrowed new money, and then lent the money to the institutional markets, flooding the markets with cash and liquidity through purchasing repos, which were investment assets for the Fed. At the same time, the Federal Reserve began borrowing even more money to fund massive purchases of the national debt - well before the pandemic - in order to keep the funding going for the government's deficit spending.

Pawning The National Debt

For the average person, the terms "repurchase agreements" and "reverse repurchase agreements" are so arcane and technical as to be meaningless. Whether it is one or the other and what that means may seem almost incomprehensible.

Just because something seems incomprehensible however, doesn't mean that it can't change all of our lives. What the Federal Reserve has been doing in recent weeks is the direct opposite of what it was doing in 2019.

The Fed needs cash to finance its purchases of the national debt. The Federal Reserve may not have the cash - but it does have collateral, it owns about $5.2 trillion of the national debt in the form of U.S. Treasury obligations.

When the Federal Reserve enters into a reverse repurchase agreement, it puts up collateral - the U.S. Treasury obligations it owns - and then borrows against that collateral. It agrees to buy back the collateral, and to pay interest through buying back the collateral at a higher price. If the Fed were to fail to buy back the collateral, then the lender would just keep the collateral.

Now, the terminology may sound arcane, but the relationship is something that much of the American public is quite familiar with. Someone needs cash. They don't have cash, but they have something of value, whether it be tools, a musical instrument, a laptop, a TV, or gold or diamond jewelry. They pledge their asset as collateral for a loan from a pawnshop and get the cash. They usually pay the loan off and get their collateral back. If they don't - then after a certain number of days, the pawnshop owns the collateral and can sell it.

While the terminology, the transaction terms (and the dress code) are quite different, the economic relationship is the same: pledging the collateral to get the loan at an interest rate, and forfeiting the collateral if the loan isn't repaid.

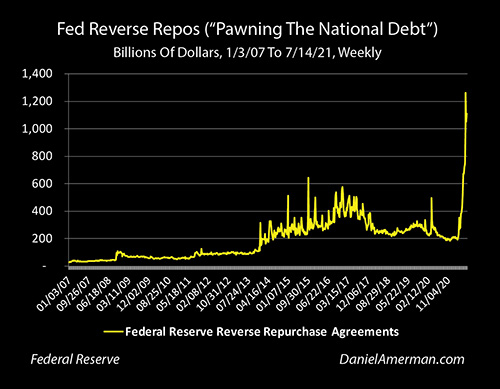

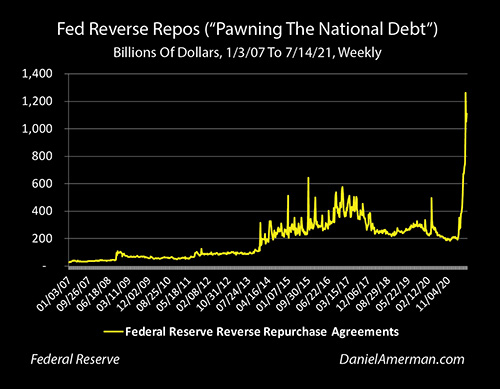

Before the Financial Crisis of 2008, when both the role of Federal Reserve and the nature of the U.S. dollar were transformed, the Fed usually had about $30 or $40 billion in reverse repos outstanding on any given day. The amount of money that the Fed borrowed on any given day pledging U.S. Treasuries as collateral grew to about $200 to $300 billion through most of the 2010s, with occasional spikes above that level.

As of the week of March 10, 2021, the Fed was borrowing about $194 billion through the use of reverse repurchase agreements. This borrowing a little more than doubled through the week of May 12th, increasing to $429 billion.

Then the Federal Reserve pledged another more than $800 billion in U.S. Treasury bond collateral over the next seven weeks, using that collateral to get more than $800 billion in new cash in just seven weeks. This was a borrowing rate of a little over $100 billion a week.

In total, the Fed "pawned" a little over $1 trillion in additional Treasuries, in order to get a little over $1 trillion in additional cash, in just 14 weeks, between the weeks of March 24th and June 30th, reaching a total of $1.26 trillion in reverse repo borrowing. This backed off very slightly the week of July 7th, and then came back up to $1.11 trillion as of July 14th, 2021.

See The Reality, See The Signal

The Federal Reserve using secured borrowings to raise cash is of course not quite the same thing as an individual with credit score problems pawning their assets to get short term cash.

The Federal Reserve is the bankers' bank for the United States, it is treated as having exceptionally high credit quality, and it’s going through the motions of pledging its assets to raise money could on the surface be called at least more a matter of convenience for the borrowers than a financial necessity for the Fed. Making secured borrowings - i.e. entering into reverse repurchase agreements - gave the Federal Reserve immediate access to an established multi trillion dollar market, with established lenders, and with an established accounting and regulatory treatment.

What really matters is that the Fed went somewhere new for new money - at least on that scale - and it did so on with massive amounts in a very short period of time. This makes no sense, or is irrelevant, if we take the highly popular but dangerously misleading approach of thinking the Fed is merely printing the money to fund the national debt. If this were actually a "counterfeiting drama", and the Federal Reserve needed an extra trillion dollars, it would merely step to the back room, flick on the printing presses (physical or electronic), print the trillion, and move on.

Crucially, there is not only no problem getting the trillion dollars with a printing press, but there is also no danger in terms of short term timing. The "problem" with this mistaken belief comes when too many dollars enter circulation, there is no risk with the inability to raise the extra trillion dollars in any given week.

The reality of debt-based money creation for banks and central banks is entirely different. Every dollar of new assets, every new dollar of Federal debt purchased, is being financed with a dollar of new debt that the Federal Reserve takes on. (Someone either understands balance sheets, or they don't.) This means there are potentially limits, every day and every week, for getting the money. The Federal Reserve had been using reserves-based money creation - the new form of money creation that first began in 2008 in the U.S. and has been the actual source of money for all the quantitative easings - but as previously reviewed, there are limits to that process.

When we switch our perspective, and look at our "crime drama" in terms of a "con job" or "shell game" (or Ponzi scheme), then the risk shifts to never running out of money, always being able to get the money from the new marks, to keep the old marks happy and the new Federal borrowings funded. If on any given day, the limits are reached, and the old lenders or the Treasury Department come to the cashier's window and want their trillion dollars and it isn't there - but the new suckers aren't there to borrow the money from - then the whole scheme can collapse on that day. (With the more likely alternative being a change to true straight up money printing on that day, as reviewed in the analysis linked here.)

When we understand that perspective and we go beneath the surface, then it is also true that if and when that day arrives when the new money isn't there, then the secured creditors of the Federal Reserve will likely be in a vastly better position than the unsecured creditors. It would therefore make sense that the closer the Fed cuts it to the edge, the more important that the ability to borrow from sophisticated investors via collateral-secured reverse repurchase agreements will become (i.e. the ability to pawn the national debt), even while the Fed would continue to publicly deny that there are any problems or that any pawning is going on.

To extend the pawnshop analogy a step further, the Fed borrowed the money to buy the collateral in the first place, call it the "guitars", and it didn't use a pawnshop, but a credit card, where it hadn't pledged the guitars as collateral. There are problems with the credit card, but the Fed still wants to keep buying guitars. So now, the Fed is pledging the guitars it had bought with the credit card, to take out new secured loans at the pawnshop, to keep the cash coming for buying still more "guitars".

Substitute "U.S. Treasury bonds and notes" for "guitars", and replace the pawnshop with the institutional fixed income marketplace, and the same financial principles apply. The Federal Reserve ran up an enormous amount of debt to increase its ownership of the national debt to over $5 trillion, at least temporary strains are developing with its unsecured borrowings, so the Fed is now taking the assets it bought with borrowed money, and pledging them as collateral to borrow the money to fund still more of the national debt.

Now, if pressed, the Fed and its enablers would strenuously deny that anything of the sort is happening. They would stress the impeccable and unquestionable credit quality of the United States government, the impeccable and unquestionable credit quality of the Federal Reserve - which by definition no serious person or expert could doubt - and then use an intentionally arcane vocabulary which the general public doesn't understand, to make clear what a ludicrous analogy the idea of pawning the national debt is. None of which would change the underlying economic essentials, which consist of borrowing the money to fund the national debt, and then taking out additional loans secured by the assets that had been bought with borrowed money, to buy still more assets and thereby fund still more of the national debt.

The Federal Reserve abruptly turning to a different market to raise the huge sums of cash needed in order to fund new Treasury purchases while paying down some other lines of credit a bit has tremendous information value when we understand that new money is created by borrowing money. This abrupt change in behavior, to seeking secured money from new borrowers on a massive scale, does mean that something major is going on.

Interpreting the information signal is a different matter than seeing the information signal. We do not know at this early point if this was a transitory move or a more permanent move when it comes to where the Fed will be getting its money from over the following months and years.

We also don't know how much of the motivation was tapping new sources of money, and how much was emergency maneuvers to try to pull money out of circulation and thereby pull down the inflation rate. The specifics of how this works may be the subject of another analysis, but reverse repos can serve a dual function for the Federal Reserve, being an emergency source of funds while also serving as an emergency inflation control measure.

Either way - the abrupt change in behavior is a powerful signal that there are major problems developing with the sources of funding for the national debt and / or rising inflation that the Fed is not willing to talk about. Actions do speak louder than words, and the actions show that beneath the Federal Reserve's projection of a calm surface, major and unprecedented actions are being taken for what are likely compelling reasons.

"Burnout" & Placing The Dollars In Perspective

The numbers involved are so vast as to seem incomprehensible, but it seems like the reaction of the average person at this point - and average investor - is to say "so what?". OK, so it was yet another trillion dollars (yawn), that came from somewhere almost no one understands - who cares?

There have been so many numbers that are so vast as to seem incomprehensible, and yet the stock and housing markets just keep setting new highs, even while businesses across the nation have difficulty finding enough employees.

It is likely just human nature to burn out, shut down and stop worrying about the vast numbers.

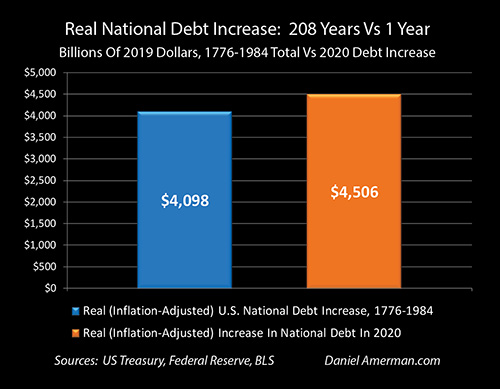

Yes, as explored in the analysis linked here, the national debt did grow by more dollars in a single year - even after adjusting for inflation - than it did in the first more than two centuries of the existence of the United States of America.

So what? The stock market is not just fine, it's great!

The balance sheet of the Federal Reserve, the sum of all of its assets, totaled less than $900 billion as of June of 2008, after the first 95 years of existence for the nation's central bank. Using an obscure borrowing method, the Fed just effectively "pawned" enough assets to raise more than $900 billion in just ten weeks. Ten weeks versus 95 years, for where the money is coming from to fund the surreal increases in the national debt.

Is anybody noticing? Does anyone care? Did you see what the housing market did last month? Let the party roll on!

The problem with living in the midst of the surreal is that it seems that reality in the normal sense of the word has been suspended. This perception then creates a paradox of sorts.

Reality is never suspended. It's there, waiting for us all, as it always has been, with the only question being the particulars of the when and the how for the reconciliation of the surreal with the real.

The paradox is that the more surreal things become - the more normal the surreal can appear to be, and the less important our former perceptions of what used to be reality can seem.

Of course, the time will come when with 20/20 hindsight it will be blindingly obvious just how crazy things got in the early 2020s. The time will come when any person with even a scrap of common sense should have seen that investment markets and currencies that are based on a central bank borrowing unprecedented - but limited - sums of money to finance unprecedented - but unlimited - increases in the national debt would turn out to be one of the worst financial mistakes of all time. It will be abundantly clear with hindsight that having all of one's retirement savings invested in assets that are dependent on the indefinite continuation of these artificial and highly elevated markets would eventually turn out to be the mistake of a lifetime.

The issue is that we aren't living in that time, we're living in the time we are in.

Human nature is that it is just really hard for the average person to go from the times we are currently in, to the place that we are likely going. Human nature and confirmation bias can make it almost impossible for an average person to see what could be called a mass financial illusion. Now, if that illusion is being very actively supported by the most powerful elements of the government and the banking system - as it is - and if it has been in place for long enough to seem normal - as it has - then piercing that facade is going to be very difficult, and therefore will not happen for most people.

An analogy for what has been explored in this analysis could be seeing a floor to ceiling crack develop on the back side of a concrete column, in the parking garage beneath a condominium complex - that hadn't been there the week before. Indeed, if we take another look at the "Fed Reverse Repos" graph, that is exactly what the recent weeks look like, an unprecedented crack leaping almost straight upwards.

The crack will not be seen by most. They may drive by it every day. Lives will be lived above it. It will seem entirely irrelevant. This could go on for quite a period of time, perhaps for years. But yet, major cracks like that shouldn't suddenly appear in a structurally sound building, and such a crack appearing has information value when it comes to the eventual future of the building.

The Federal Reserve effectively pawning about a trillion dollars of its ownership of the national debt in order to raise a trillion dollars in new money from new sources within about three months is a major new crack in the structural foundation of our financial system, that didn't exist before the spring of 2021. It simply didn't exist - but now it does. Hopefully this analysis has been useful for you when it comes to seeing the new crack, and some of the possible implications.