The Pentagon will become the largest shareholder in MP Materials, the only rare earths miner in the United States, after agreeing to buy $400 million of its preferred stock, the company said on July 10th.

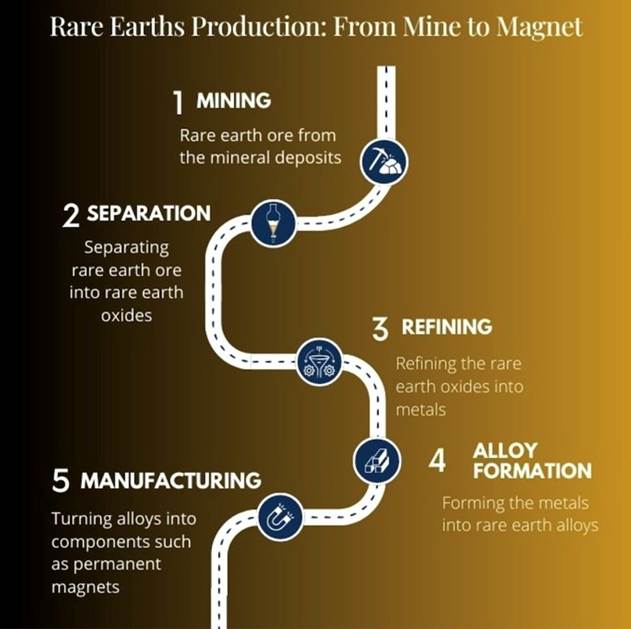

Proceeds from the investment will be used to expand MP’s rare earths processing capacity and permanent magnet production.

Until recently, MP Materials dug up predominantly light rare earth elements from Mountain Pass and sent them to China for processing — leading to accusations that the company was “owned” by China and did nothing to transform the United States from a rare earth miner to a rare earth refiner and permanent magnets producer.

The company is owned by US hedge funds JHL Capital Group and QVT Financial LP, along with its CEO, James Litinsky, who collectively hold a 51.8% stake. Shenghe Resources, a Chinese company with partial state ownership, holds an 8% stake.

Shenghe was the company doing the processing; however, this stopped in April 2025, when MP Materials ceased shipping rare earth concentrate to China following China’s imposition of rare earth export controls and retaliatory tariffs.

In January of this year, the company commenced commercial production of neodymium-praseodymium (NdPr) metal and trial production of automotive-grade, sintered neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets at its Independence facility in Fort Worth, Texas.

According to the company, NdFeB magnets are “the world’s most powerful and efficient permanent magnets — essential components in vehicles, drones, robotics, electronics, and aerospace and defense systems.”

The facility will supply NdFeB magnets to General Motors and other auto manufacturers, sourcing its raw materials from Mountain Pass.

The Pentagon deal

The Pentagon clearly sees rare earths as important. A CNBC article on the Pentagon-MP Materials deal says that, according to the Defense Department, Rare earths are used in magnets that are key components in a range of military weapons systems, including the F-35 warplane, drones, and submarines.

The U.S. was almost entirely dependent on foreign countries for rare earths in 2023, with China representing about 70% of imports, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Rare earths have been a central point of contention in recent trade disputes between the U.S. and China.

In early April, China imposed export controls on seven rare earth elements (REEs) and related permanent magnets, citing national security concerns and US tariffs. The targeted REEs were samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, scandium, and yttrium.

On June 11, US and Chinese officials finalized a new trade framework following two days of negotiations in London. According to the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), the agreement includes a commitment from Beijing to resume exports of rare earth elements and magnets to the United States, following two months of severe export restrictions that disrupted key inputs for the automotive, robotics, and defense sectors.

Now comes the Pentagon-MP Materials deal. As stated by CNBC:

MP Materials CEO James Litinsky described the Pentagon investment as a public-private partnership that will speed the buildout of an end-to-end rare earth magnet supply chain in the U.S…

The Pentagon is buying a newly created class of preferred shares convertible into MP Materials’ common stock, in addition to a warrant convertible at $30.03 a share for 10 years that allows the U.S. to buy additional common stock.

Exercising the convertible preferred shares and the warrant would leave the Pentagon holding about a 15% stake in MP Materials as of July 9, nearly twice the 8.61% held by Litinsky and the 8.27% held by BlackRock Fund Advisors, according to FactSet data.

Aside from taking a 15% stake in MP Materials, another important aspect of the agreement is a plan for MP to build a second magnet manufacturing facility in the US. While the location was not disclosed, CNBC says the facility is expected to be commissioned in 2028 and bring MP’s magnet capacity to 10,000 tonnes annually, from an initial 1,000 tonnes at Independence.

The Pentagon has agreed to buy all of the magnets made at the facility called 10X for a decade after the plant is built. It is also guaranteeing a minimum price of $110 per kilogram for neodymium-praseodymium oxide (NdPr), which is used to make the permanent magnets.

MP Materials also expects to receive a $150 million loan in 30 days from the Pentagon to expand its rare earth separation capabilities at Mountain Pass, CNBC states.

The $400 million Pentagon-MP Materials deal got me thinking. The Defense Department and the Pentagon obviously see rare earths as among the most highly ranked critical minerals, due to their civilian and military applications. But there is another critical mineral that is also crucial to military and non-military uses — graphite. REEs and graphite share other similarities, which we get into below.

In this article, we are defending the position: Graphite is at least as critical, if not more critical, than rare earth elements.

The next big thing

As far back as 2012, rare metals expert Jack Lifton said he sees graphite as “the next big thing” following the lithium and rare earths craze of the early 000’s.

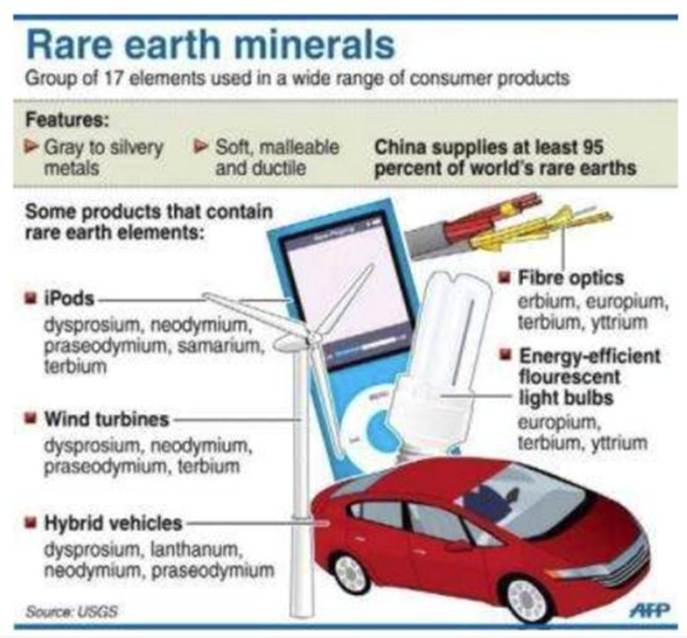

In an interview with The Critical Metals Report, Lifton said, “Graphite has traditionally been considered a boring, mundane industrial mineral, evoking thoughts of pencils, golf clubs, and tennis racquets. Investors should think again. Traditional demand for graphite in the steel and automotive industries is growing 5% annually, and graphite prices have tripled. New applications such as heat sinks in computers, lithium-ion batteries, fuel cells, and nuclear and solar power are all big users of graphite. These consumers are beginning to place substantial demands on existing production, and over 70% of that production is from China, which is no longer selling this resource cheaply to the rest of the world as the country’s easy-to-mine, near-surface deposits are becoming exhausted.”

“Graphite’s criticality and potential scarcity have been recognized by both the United States and the European Union, which have each declared graphite a supply-critical mineral. Recently, the British Geological Survey ranked graphite right behind the rare earths and substantially ahead of lithium in terms of supply criticality. Clearly, there is much more to graphite than pencils.”

Lifton noted that graphite has a two-dimensional flake crystal structure and that the material is a very good conductor of heat and electricity. Graphite is used in the anodes of lithium-ion batteries, and each battery contains nearly four times more graphite than lithium.

Other future uses of graphite include:

- Fuel cells, where the proton exchange membrane fuel cells are being developed for use in cars, would require 100 pounds of graphite per vehicle.

- Next-generation nuclear reactors, which are expected to reach temperatures of 1,000 degrees Celsius — triple the temperature inside today’s commercial reactors. Graphite is one of the few substances that can resist such heat, and

- The vanadium redox battery, which offers great potential for storing excess energy generated by renewable energy sources like wind turbines and solar cells, is another notable emerging technology that would require significant amounts of graphite to produce. These batteries, which offer significant storage capacity, long life, low maintenance requirements, and a nominal environmental footprint, require some 300 tons of flake graphite per 1,000 megawatt of storage capacity.

Everything Lifton says is still relevant.

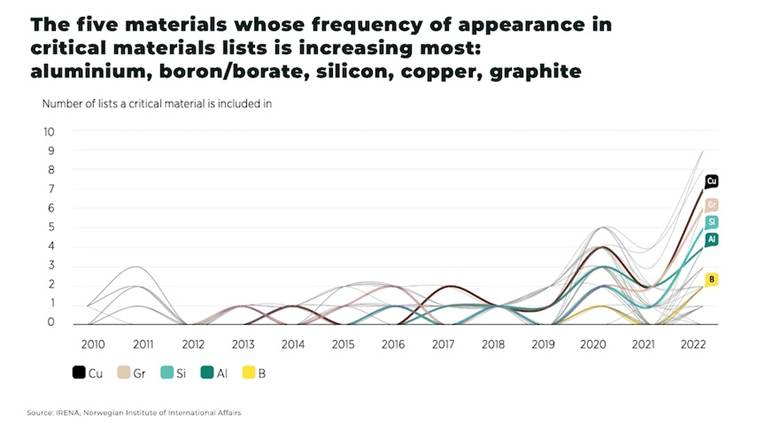

The Oregon Group quotes a 2024 report by the International Renewable Energy Agency that ranked the following metals as “most critical” for the transition to renewable energy:

- lithium

- cobalt

- gallium

- rare earth elements (REEs)

- neodymium

- indium

- platinum group metals (PGMs)

- dysprosium

- nickel

- tellurium

- praseodymium

- graphite

- manganese

- copper

- germanium

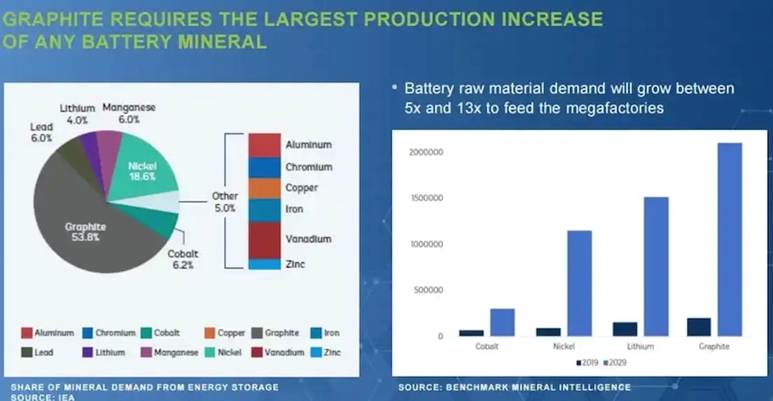

Investor News reported in 2023 that graphite requires the largest production increase of any battery mineral to meet forecast demand — 53.8% compared to just 4% for lithium, 6.2% for cobalt, 6% for lead and manganese, and 18.6% for nickel.

Military uses

Rare earths

Neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets, or just neodymium magnets, are critical for electric vehicles, robots and wind turbines. They are also used in defense applications. A paper titled ‘America’s Dependence On and Need to Secure Its Supply of Permanent Magnets’ by USAF Lieutenant Colonel Justin Davey states that “Neodymium and samarium… have a disproportionate influence on all high technology businesses, especially the defense industry.”

They combine with other elements (specifically iron, boron, and cobalt) to make exceptional permanent magnets. Samarium-cobalt (SmCo) magnets have the highest known resistance to demagnetization. This capability, meaning the magnet has higher coercivity, allows them to function in high-temperature environments without losing magnetic strength — an essential attribute for most military applications.

Samarium-cobalt magnets were first introduced in the 1970s. They are stronger than alnico or ceramic material and offer the best heat resistance of all the permanent magnet types, with the ability to withstand temperatures up to 300 degrees C. However, due to their higher cost, they are less popular than the most common rare earth magnet, NdFeB. Samarium-cobalt magnets are highly resistant to rusting, but they are also brittle and may fracture when extreme heat causes them to expand.

Terbium and dysprosium are sometimes added to NdFeB magnets to allow them to tolerate even higher temperatures.

“Miniature high-temperature resistant permanent magnets are a key factor in developing state-of-the-art military technology,” Lieutenant Colonel Davey’s paper continues. “They pervade the equipment and function of all service branches, starting with commercial computer hard drives containing NdFeB magnets that sit on nearly every Department of Defense (DOD) employee’s desk.”

Precision-guided munitions depend on SmCo magnets as part of the motors that manipulate their flight control surfaces. Without these advanced tiny magnets, the motors in “smart bombs,” like the joint direct attack munition (JDAM), would require a hydraulic system that is more expensive and three times as large.

The generators that produce power for aircraft electrical systems also rely on samarium-cobalt magnets, as does the stealth technology used to mask the sound of helicopter rotor blades by generating white-noise concealment. Other permanent magnet applications include “jet engines and other aircraft components, electronic countermeasures, underwater mine detection, antimissile defense, range finding, and space-based satellite power and communications systems,” according to the USGS.

The Army relies on REE magnets for the navigation systems in its M1A2 Abrams battle tank and the Navy is developing a similarly dependent electric drive to conserve fuel for its Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. The Air Force’s F-22 fighter uses miniaturized permanent magnet motors to run its tail fins and rudder.

According to the US Department of Defense,

Since 2020, DOD has awarded more than $439 million to establish domestic rare earth element supply chains. This includes separating and refining rare earth elements mined in the U.S., as well as developing downstream stateside processes needed to convert those refined materials into metals and then magnets.

In addition to the F-35, Virginia and Columbia class submarines, magnets produced from rare earth elements are used in systems such as Tomahawk missiles, a variety of radar systems, Predator unmanned aerial vehicles, and the Joint Direct Attack Munition series of smart bombs. The F-35, for instance, requires more than 900 pounds of rare earth elements. Each Arleigh Burke DDG-51 destroyer requires 5,200 pounds, and a Virginia-class submarine needs 9,200 pounds.

Anti-ballistic missiles like Israel’s “Iron Dome” use samarium-cobalt and neodymium magnets for various functions within the missile’s guidance and control systems.

Rare earths are central to the whole spectrum of defense technologies that are vital to every military. Without them, countries would be unable to produce much of the military hardware and equipment required for national defense. In most cases, there are no substitutes.

Moreover, switching from current suppliers (i.e., China) would cause major disruptions to supply chains. According to the US Government Accountability Office, it would take 15 years to overhaul the defence supply chain, meaning any changes to it need considerable lead time.

Apart from permanent magnets, of which the US military is an important buyer, other applications of rare earth elements include:

- Radar and sonar are used to prevent collisions, for surveillance, and as navigational aids. The Patriot Missile Air Defense System employs radio frequency circulators to magnetically control the flow of electronic signals in the radar and missiles. Rare earths required: gadolinium, samarium, yttrium.

- Communications and displays required by soldiers, sailors, and airmen to see analog and digital data. Examples are lasers that help line-of-sight communication links in satellite and ground-based systems; old and new computer monitors; and avionics terminals. Rare earths required: dysprosium, erbium, europium, neodymium, praseodymium, terbium, and yttrium.

- Lasers are employed on vehicle-mounted systems like tanks and armored vehicles. They can identify enemy targets up to 22 miles. According to DefenseMediaNetwork, “The laser-equipped computer main gun sight on the Abrams M1A/2 tank combines a Raytheon rangefinder and integrated designator targeting system used to obtain a high-probability first hit.” Rare earths required: europium, neodymium, terbium, and yttrium.

- Precision-guided munitions (PGMs) include a number of missile classes, including cruise, anti-ship (ASM), and surface-to-air (SAM), as well as bunker busters. The heat-seeking AIM-9 Sidewinder missile has four fins on its fuselage that use rare-earth magnets to control its flight trajectory. Rare earths required: dysprosium, neodymium, praseodymium, samarium, and terbium.

- Guidance and control systems that steer missiles and bombs towards their targets. Rare earths required: terbium, dysprosium, samarium, praseodymium, and neodymium.

- Electronic warfare refers to a range of equipment that includes high-capacity power sources, storage batteries, and electronic jamming devices. Rare earths required: yttrium-iron-garnet.

- Jet engines. The rare earth element erbium is added to vanadium to make it more malleable for use in vanadium-infused steel that goes into jet engines. While not specifically a rare earth element, the rare element rhenium is alloyed with molybdenum and tungsten. The F-22 Raptor and the F-35 Lightning II stealth fighter reportedly use 6% rhenium in their engines. The electrical systems in aircraft employ samarium-cobalt permanent magnets to generate power.

Graphite

Graphite is the ideal material for defense purposes thanks to its unique properties, i.e., it is able to withstand very high temperatures with a high melting point; it is stable at these high temperatures; it is lightweight and easy to machine; and it is corrosion-resistant.

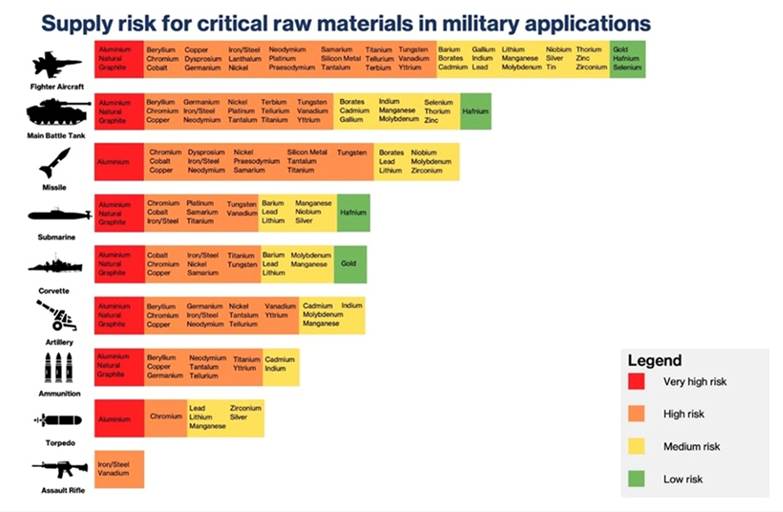

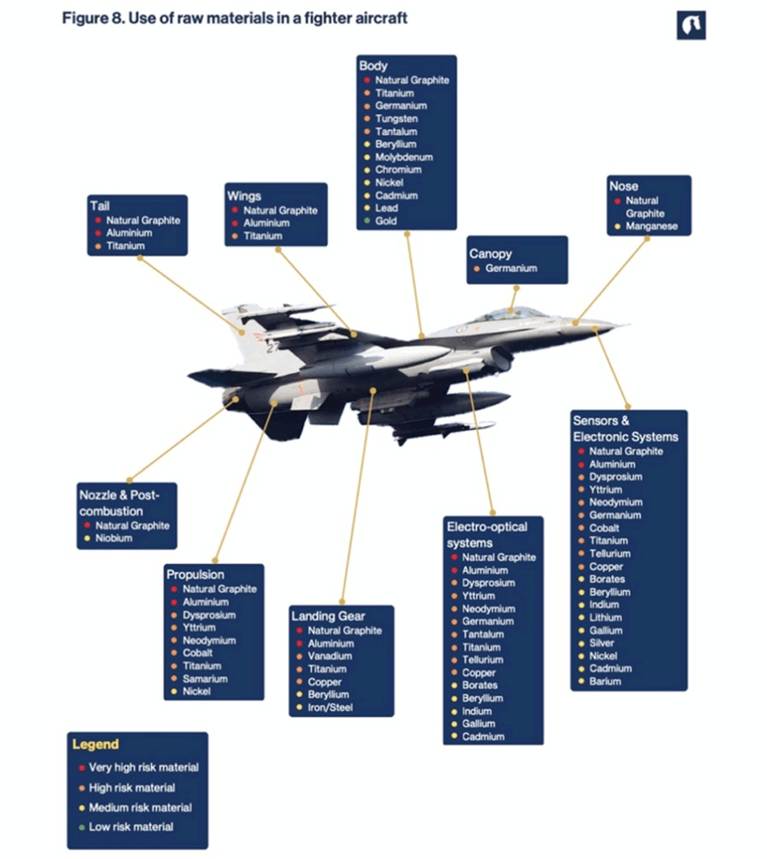

A recent report from the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies found that natural graphite and aluminium are the materials most commonly used across military applications and are also subject to considerable supply security risks that stem from the lack of suppliers’ diversification and the instability associated with supplying countries.

The report assessed the degree of criticality for each of 40 materials deemed critical or soon to be critical. Natural graphite was rated “very high-risk” for air applications, and “high-risk” for sea applications.

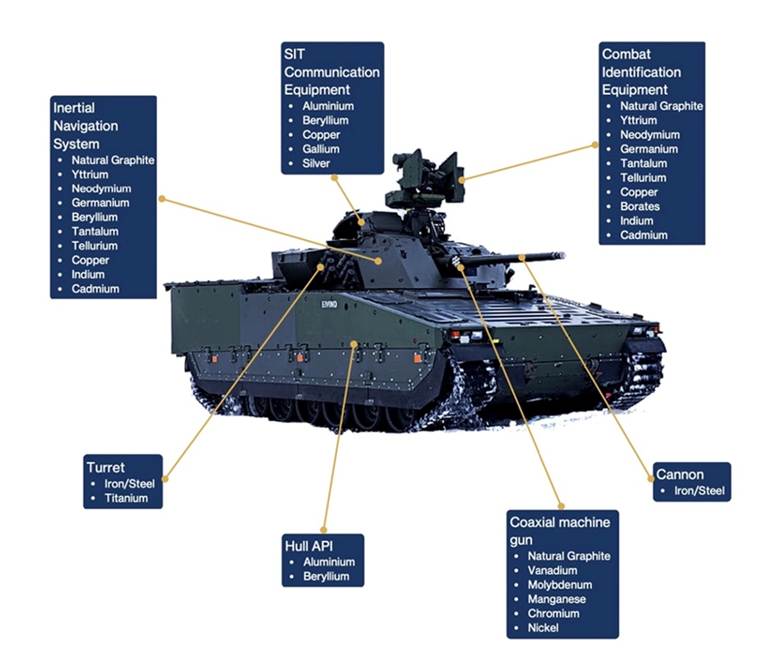

In the table below, natural graphite is rated red, very high risk, for its use in fighter aircraft, main battle tanks, submarines, corvettes, artillery, and ammunition. Aluminum, used in fighters, tanks, missiles, submarines, corvettes, artillery, ammunition, and torpedoes, was also rated a very high-risk material.

The report says aluminum and natural graphite are the two most used materials in the defence industry and can be found in aircrafts (fighter, transport, maritime patrol, and unmanned), helicopters (combat and multi-role), aircraft and helicopter carriers, amphibious assault ships, corvettes, offshore patrol vessels, frigates, submarines, tanks, infantry fighter vehicles, artillery, and missiles. These materials are used in components such as airframes and propulsion systems of helicopters and aircraft, as well as onboard electronics of aircraft carriers, corvettes, submarines, tanks, and infantry fighter vehicles. The impact of supply security disruption would hence be very significant, given the multiplicity of aluminum and natural graphite’s applications.

In the fighter plane graphic below, notice the use of natural graphite (red dots) in almost every part of the plane, including the body, wings, tail, nose, nozzle, propulsion system, landing gear, electro-optical systems, and sensors and electronic systems.

According to the report, the most used of the 40 materials across the air domain are aluminum, natural graphite, copper, and titanium:

These materials have several applications in aeronautics. In aircraft (fighter, transport, maritime patrol, and unmanned) and helicopters (combat and multi-role), aluminium, natural graphite, and titanium find their main application in the airframe, where they are used in the body, wings, tail, nose, and axis of the aircraft. They are also employed in the production of propulsion systems’ components such as combustors, nozzles, drive shafts, and propellers, as well as in landing gears, connectors, and electronic systems.

A second graphic of a tank shows natural graphite in the inertial navigation system, combat identification equipment, and a coaxial machine gun.

According to the report, for the construction of tank guns, Howitzer machine guns in infantry fighter vehicles, and GPS/SAL guidance systems in ammunition, natural graphite is found in combination with other materials to construct these components.

Graphite’s war-fighting capabilities – Richard Mills

Civilian uses

Rare earths

Rare earth permanent magnets are not only essential components in a range of defense capabilities, but also a critical part of commercial applications. They are also used to generate electricity for electronic systems in aircraft and focus microwave energy in radar systems, according to the Department of Defense.

Neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets are incredibly strong — the most powerful commercial magnet available. Compared to an equal mass of traditional ferrite magnet, an NdFeB magnet has over 10 times the magnetic energy product. Accordingly, a much smaller amount of magnet is required for any particular application. This attribute makes them ideal for the miniaturization of motors, electronics, and electrical components.

Neodymium-iron-boron magnets have similar properties to their samarium-cobalt cousins, except they are less resistant to oxidation, needing a surface treatment, and can’t withstand such high temperatures.

Many rare earth applications are highly specific, and substitutes are inferior or unknown:

- Color cathode-ray tubes and liquid-crystal displays used in computer monitors and televisions employ europium as the red phosphor.

- Terbium is used to make green phosphors for flat-panel TVs and lasers.

- Lanthanum is critical to the oil refining industry, which uses it to make a fluid cracking catalyst that translates into a 7% efficiency gain in converting crude oil into refined gasoline.

- Rechargeable batteries

- Automotive pollution control catalysts

- Neodymium is key to the high-strength permanent magnets used to make high-efficiency electric motors. Two other REE minerals – terbium and dysprosium – are added to neodymium to allow it to remain magnetic at high temperatures.

- Fiber-optic cables can transmit signals over long distances because they incorporate periodically spaced lengths of erbium-doped fiber that function as laser amplifiers.

- Cerium oxide is used as a polishing agent for glass. Virtually all polished glass products, from ordinary mirrors and eyeglasses to precision lenses, are finished with CeO2.

- Gadolinium is used in solid-state lasers, computer memory chips, high-temperature refractories, and cryogenic refrigerants used to improve high-temperature characteristics of iron, chromium, and related alloys.

- Y, La, Ce, Eu, Gd, and Tb are used in energy-efficient fluorescent lamps. These light bulbs are 70% cooler in terms of the heat they generate and are 70% more efficient in their use of electricity.

- REEs are used in metallurgy as an alloying agent to desulfurize steels, as a nodularizing agent in ductile iron, as lighter flints, and as alloying agents to improve the properties of superalloys and alloys of magnesium, aluminium, and titanium.

- Rare earth elements are used in the nuclear industry in control rods, as dilutants, and in shielding, detectors, and counters.

- Rare metals lower the friction on power lines, thus cutting electricity leakage.

Graphite

Graphite is found in a wide range of consumer devices, including smartphones, laptops, tablets, and other wireless devices, earbuds, and headsets.

The electrification of the global transportation system doesn’t happen without graphite.

That’s because the lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles are composed of an anode (negative) on one side and a cathode (positive) on the other. Graphite is used in the anode.

The cathode is where metals like lithium, nickel, manganese, and cobalt are used, and depending on the battery chemistry, there are different options available to battery makers. Not so for graphite, a material for which there are no substitutes.

Graphite is the largest component in batteries by weight, constituting 45% or more of the cell. Nearly four times more graphite feedstock is consumed in each battery cell than lithium and nine times more cobalt.

It may surprise some to learn that graphite is found in internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles as well as EVs.

Graphite is used in lead-acid batteries, particularly in advanced lead-acid batteries used in vehicles with start-stop systems and regenerative braking. It’s also used in other automotive applications, including brake linings, gaskets, and clutch materials.

Besides being integral to lead-acid and electric car batteries (plus e-bikes and scooters), graphite is used in pencil lead, lubricants and repellants, paints, and refractories.

As mentioned near the top, future uses of graphite include fuel-cell vehicles, next-generation nuclear reactors, and batteries that store intermittent renewable energies like wind and solar.

Multiplier effects

Rare earths are great multipliers; they are used in making everything from computer monitors and permanent magnets to lasers, guidance control systems, and jet engines.

The “multiplier effect” on rare earth elements refers to the significant impact their use has across various industries, particularly in clean energy technologies, electronics, and defense, leading to a ripple effect of economic activity.

For example, the global dysprosium market was valued at $5.59 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach $8.82 billion by 2032, driven by increasing demand in sectors like electric vehicles and wind turbines.

The global wind turbine market was roughly $98.6 billion in 2020, and is forecast to reach $144B by 2027. At a CAGR of 5.6%, this would put the value at $116.1B in 2023. Dysprosium has a multiplier effect of 20.7 for wind turbines.

In 2023, the global electric vehicle market was valued at $500 billion. Dysprosium’s multiplier for EVs is 89.5.

Dysprosium is required for electric motors to operate at high temperatures.

The global scandium market was estimated at $591.5 million in 2024. One of the biggest uses of scandium is in aluminum-scandium alloys used in the aerospace industry. The global aerospace market was valued at around $346 billion, giving scandium a multiplier of 584.

While not a rare earth element, tungsten gets an honorable mention.

The tungsten market was valued at $4.75 billion in 2023. Tungsten is used to make ammunition. The global ammunition market, which includes bullets and other types of ammunition, was valued at around $28.10 billion in 2023, giving tungsten a multiplier of 5.9.

The multiplier effect for graphite refers to the increased demand for graphite and related industries due to its crucial role in clean energy technologies, particularly batteries, EVs, and energy storage systems. The result is increased economic activity, job creation, and investment in these industries.

For example, the battery sector’s demand for graphite is forecast to rise by over 1,400% between 2020 and 2050. By the end of that period, total graphite demand could be three times the 2021 supply level. Growth is primarily driven by the expanding EV market and the need for energy storage to support renewable energy sources.

Mordor Intelligence says the North American battery market is expected to grow from $16.1 billion in 2024 to $68.9B in 2029, a CAGR of 33.7%

A report by Polaris Research valued the global anode market at $11.5 billion in 2023. By 2032, revenues should reach $123.7B, with the industry growing at a CAGR of 30.9%.

Controlled by China

Rare earths

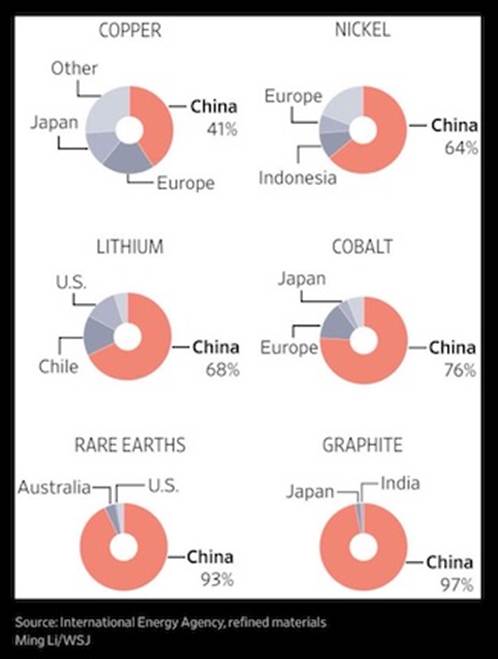

China has a tight grip on processing critical minerals, meaning it can weaponize them during conflicts with its adversaries, as it has done before with Japan (rare earths), and the United States with export controls on gallium, germanium, graphite, antimony, and rare earths.

In December 2023, China banned the export of technology to make rare earth magnets.

As mentioned, on April 4th, 2025, China imposed controls on the export of seven rare-earth minerals to the US: scandium, samarium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, lutetium, and yttrium.

China weaponizes rare earths in retaliation for escalated US tariffs — Richard Mills

For decades, China has dominated critical minerals, with Canada and the US, among other nations, all too willing to let Beijing do the mining and/ or processing and sell the end products, such as rare earth magnets, back to us.

Thanks to its technological prowess in refining and its willingness to forgo all environmental safeguards, China has established itself as the across-the-board leader in the rare earth/ critical mineral processing business.

Graphite

As shown in the graphic below, China’s global graphite dominance is higher than its dominance of rare earths.

China is by far the biggest graphite producer at about 80% of global production. It also controls almost all graphite processing, establishing itself as a dominant player in every stage of the supply chain.

China accounts for 98% of announced anode manufacturing capacity expansions through 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.

The Asian nation also controls 80% of synthetic graphite production, which currently dominates the market over natural graphite. Synthetic graphite’s primary application is in the graphite electrodes used for electric arc furnace steelmaking, which accounts for 70-80% of graphite electrode consumption.

China has imposed restrictions on Chinese graphite exports. Exporters must apply for permits to ship synthetic and natural flake graphite. Note that while export restrictions have been eased by China on rare earths, they remain in place for graphite.

The United States currently produces no graphite and therefore must rely solely on imports to satisfy domestic demand. Primary sources are China, Mexico and Canada.

Government funding and building supply chains

Rare earths

The Department of Defense (DOD), in its 2024 National Defense Industrial Strategy, set a target to establish a fully integrated mine-to-magnet rare earth supply chain capable of meeting all US defense requirements by 2027. Since 2020, the DOD has invested over $439 million to strengthen domestic supply chains. This includes a $9.6 million award to MP Materials in 2020 under the DPA Title III program to develop a light rare earth separation facility at Mountain Pass, California, followed by a $35 million award in 2022 for a heavy rare earth processing facility.

According to Bloomberg, Officials are discussing using the Defense Production Act to tap financing, loans, and other means for rare earths element-related projects, including mining, processing, and other downstream technologies to bolster the US’s capability to build a domestic supply chain, the people said…

The US currently lacks the so-called mine-to-magnet capability at scale, and invoking the emergency authority will give the Defense Department and other agencies tools to speed up sourcing that severely lags China’s dominance in the industry. The urgency has only increased since Beijing flexed its rare earths capacity as leverage in trade talks with Washington over the past month.

While short on details, the article says that MP Materials, operator of Mountain Pass and the only current domestic producer of rare earths, “would be a prime beneficiary.”

Of course, we now have the Pentagon paying $400 million to take a 15% stake in MP Materials.

Graphite

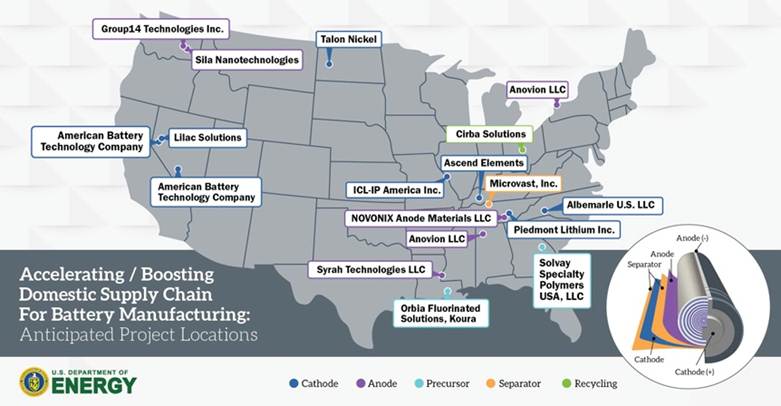

In 2022, the Biden administration announced $2.8 billion in Department of Energy funding through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The projects, states the DoE, “will support new and expanded commercial-scale domestic facilities to process lithium, graphite and other battery materials, manufacture components, and demonstrate new approaches, including manufacturing components from recycled materials.” The release named 21 applicants; 18 are on the map below.

In October 2022, DoE awarded $486 million to three graphite projects that will produce about 110,000 metric tons per year of anode-grade material. Unfortunately, the projects weren’t named.

One company that has been attracting a lot of attention from government funders, officials and investors is Graphite One (TSXV:GPH, OTCQX:GPHOF).

Graphite One (TSXV:GPH, OTCQX:GPHOF)

The Vancouver-based company plans to invest $435 million to build a graphite anode manufacturing plant in Trumbull County, Ohio, between Cleveland and Pittsburgh.

As Graphite One builds its anode active materials (AAM) production plant, first to accommodate synthetic graphite, then natural graphite from the Graphite Creek mine, the company has the opportunity to make other graphite products. Two possibilities are silicon-blend graphite, where silicon is embedded within a graphite matrix in the anode, and hard carbon, which improves ionic flow and provides higher power densities in batteries.

On July 25, 2024, G1 announced it has entered into a non-binding Supply Agreement with Lucid Group, Inc. (NASDAQ: LCID), a California-based electric vehicle manufacturer, for synthetic graphite (SG) AAM used in EV batteries.

“This is a historic moment for Graphite One, Lucid, and North America: the first synthetic graphite Supply Agreement between a U.S. graphite developer anda U.S. EV company,” said Anthony Huston, Graphite One’s president and CEO.

“G1 is excited to continue pushing forward, developing our 100% U.S. domestic supply chain. We appreciate the support from our investors and the grant from the Department of Defense,” Huston continued. “Subject to project financing required to build the AAM facility, the Supply Agreement with Lucid puts G1 on the path to produce revenue in 2027, and that’s just the beginning for Graphite One as work to meet market demands and create a secure 100% U.S.-based supply chain for natural and synthetic graphite for U.S. industry and national security.”

The Supply Agreement follows Graphite One’s selection in March 2024 of a site for the company’s proposed AAM facility in Warren, Ohio.

Through its wholly owned subsidiary, Graphite One Alaska, GPH chose Ohio’s Voltage Valley, entering into a 50-year land-lease agreement on 85 acres. The deal also contains an option to purchase the property, once known as the Warren Depot, part of the National Defense Stockpile infrastructure, until the brownfield site was processed through the Ohio EPA Voluntary Action program a decade ago, certifying that the land does not need further cleanup.

Construction is slated to start within the next two years. According to Graphite One, the Voltage Valley site is in the heart of the automobile industry, with ample low-cost electricity produced from renewable energy sources. It is accessible by road and rail, with nearby barging facilities. Existing power lines are sufficient for Graphite One’s Phase 1 production target of 25,000 tonnes per year of battery-ready anode material. Land is available for follow-on phases to ramp up to 100,000 tpy of production.

The five-year, non-binding Supply Agreement provides for 5,000 tpa of synthetic graphite. Sales are based on an agreed price formula linked to future market pricing, as well as satisfying base-case pricing agreeable to both parties.

The Ohio facility represents the second link in Graphite One’s graphite materials supply chain; the first link is Graphite One’s Graphite Creek mine in Alaska.

Subject to financing, the plant will manufacture synthetic graphite until natural graphite becomes available from the company’s Graphite Creek mine, located near Nome, Alaska, according to the March 20th news release.

The plan also includes a recycling facility to reclaim graphite and other battery materials, to be co-located at the Ohio site, which is the third link in Graphite One’s circular economy strategy.

FAST-41

Graphite One in June reached a major milestone on the road to production at its Graphite Creek mine.

The company announced on June 3 that the Graphite Creek project in Alaska — the upstream anchor for Graphite One’s complete US-based graphite supply chain — has been accepted as a “covered project” on the US government’s “FAST-41 Permitting Dashboard”.

Graphite Creek is the first Alaskan mining project to be listed on the dashboard.

“The approval of Graphite Creek as FAST-41’s first Alaskan mining project is a major step for G1 and our complete U.S.-based supply chain strategy,” Huston said in the June 3 news release. “With President Trump’s Critical Mineral and Alaska Executive Orders, Graphite One is positioned at the leading edge of a domestic Critical Mineral renaissance that will power transformational applications from energy and transportation to AI infrastructure and national defense.”

FAST-41 streamlines the permitting process by providing improved timeliness and predictability by establishing publicly posted timelines and procedures for federal agencies, reducing unpredictability in the permitting process. FAST-41 also provides issue resolution mechanisms, while the federal permitting dashboard allows all project stakeholders and the general public to track a project’s progress, including periods for public comment.

The Graphite Creek project is found on page 2 of the FAST-41 Covered Projects, which are listed in alphabetical order. The Department of Defense and the US Army Corps of Engineers are listed as the agencies responsible for the project, which has a status of “Planned”.

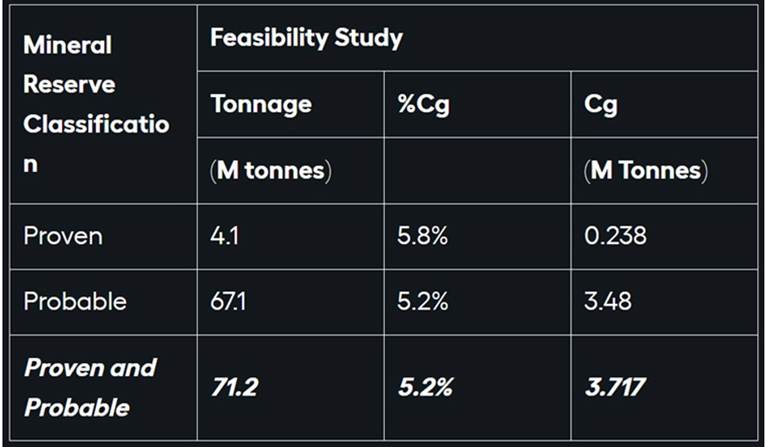

Feasibility Study

FAST-41 status follows publication of Graphite One’s Feasibility Study (FS) on April 23, which, with the support of the Department of Defense Production Act award ($37.5 million), was completed 15 months ahead of schedule. Annual graphite concentrate capacity of the Graphite Creek mine in the FS was increased from that in the 2022 Prefeasibility Study (PFS) from 53,000 tonnes per year (tpy) to 175,000 tpy while maintaining a 20-year mine life. Measured plus Indicated Resources increased to 322% of the PFS resource estimate. The FS projects a post-tax internal rate of return of 27%, using an 8% discount rate, with a net present value of $5.03 billion and a payback period of 7.5 years.

President Trump has signed several executive orders of relevance to Graphite One and Graphite Creek.

Regarding Trump’s March 20 executive order, Graphite One said it welcomes the EO, titled “Immediate Measures to Increase American Mineral Production.”

“This new Critical Minerals Executive Order serves as the strongest signal yet that the U.S. Government has not only recognized the national security need for critical minerals, including graphite, but that there will now be a ‘whole of government’ engagement to accelerate domestic development,” Graphite One’s CEO Anthony Huston said.

The full text of the executive order can be found here, on the presidential actions page of the White House website.

The Critical Minerals EO follows three executive orders issued by President Trump on his first day in office: “Declaring a National Energy Emergency,” “Unleashing American Energy,” and “Unleashing Alaska’s Extraordinary Resource Potential,” referenced in the Jan. 23 Graphite One press release.

The EO tasks the secretaries of defense, energy, and interior with actions requiring responses within 10, 15, 30, and 45 days, and waives related legal requirements under the “national emergency” provision of the Defense Production Act (DPA).

The EO aligns with the focus on Alaska’s role in US resource development, hosting 49 of the 50 US government-designated critical minerals. As Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy noted in his 2025 State of the State address, “the Graphite One deposit, the largest in North America, north of Nome, continues to move ahead with support from a Defense Department grant. Subject to securing project financing, construction could begin by 2027, and the mine could be producing as early as 2029.”

Grants and loans

Two Department of Defense grants have been awarded to Graphite One, one for $37.5 million – paying 75% of the cost of the Feasibility Study, the other for $4.7 million — the latter to develop an alternative to the current firefighting foam used by the US military and civilian firefighting agencies, using graphite sourced from Graphite Creek.

In addition, G1 qualifies for federal loan guarantees worth $72 billion.

G1 has also received a $325 million non-binding Letter of Interest from the EXIM Bank for the construction of the company’s Ohio-based anode manufacturing plant. Both DPA and EXIM are among the agencies that will have expanded critical mineral authorities under the new EO.

Thanks to the FS, the Graphite Creek project has entered the permitting phase with a production rate triple that was projected two years ago in the PFS.

Achieving US security of supply

The US could soon have security of supply for a critical mineral that they are currently 100% reliant on China for.

As mentioned, China is by far the biggest graphite producer at about 80% of global production. It also controls almost all graphite processing, establishing itself as a dominant player in every stage of the supply chain.

China has imposed restrictions on Chinese graphite exports. Exporters must apply for permits to ship synthetic and natural flake graphite.

Up to now, the US has had no security of supply for graphite. The country has reached a point where much more graphite needs to be discovered and mined in the US.

Graphite One could take a leading role in loosening China’s tight grip on the US graphite market by mining feedstock from its Graphite Creek project in Alaska and shipping it to its planned graphite product manufacturing plant in Voltage Valley, Ohio.

Consider: In 2024, the US imported 60,000 tonnes of natural graphite, of which 87.7% was flake and high purity.

The Feasibility Study anticipates tripling the production rate envisioned in the PFS, which would be 155,439 tonnes, meaning Graphite One could have the capacity to not only meet the US’s annual graphite needs, but have extra to stockpile, in the neighborhood of 100,000 tonnes each year. This additional graphite could be put to domestic usage or built up to accommodate future demand growth.

All of this is based on the results of just 1.9 km of the 15.3-km-long geophysical anomaly. The resource remains open down dip and along strike to the east and west. Graphite Creek is now triple the size when the US Geological Survey reported three years ago that it was the largest flake graphite deposit in the US. And it could get even bigger with further exploration. We are talking about a potential life of mine (LOM) that provides all the graphite the US needs, spanning across generations.

Conclusion

Rare earths and graphite share several commonalities, which we have outlined in this article. Both metals have military and civilian applications, multiplier effects, and are controlled by China. The United States is import-dependent on both, but Washington is fighting back through executive orders and billions in government funding to help develop US “mine to magnet” and “mine to anode” supply chains.

MP Materials and Graphite One are the furthest ahead in this respect. Remember what CNBC said about the Pentagon-MP Materials deal:

MP Materials CEO James Litinsky described the Pentagon investment as a public-private partnership that will speed the buildout of an end-to-end rare earth magnet supply chain in the U.S.

Meanwhile, Graphite One’s Feasibility Study has come out during an interesting time in the graphite market. China has imposed restrictions on graphite exports. Increased usage of natural graphite is expected from non-Chinese sources, who are seeking to establish ex-China supply chains. Graphite One is at the forefront of this trend.

President Trump wants to expand production of critical minerals in America. On March 20th, he set out the boldest measures the mining industry has seen in decades, with an executive order that aims to speed up permitting, prioritize land-use for mining, and provide financial support.

The company has significant financial backing from the Department of Defense, a letter of interest from the Export-Import Bank of the United States to provide up to $325 million of debt financing, and political support from the highest levels of government, including the White House, Alaska senators, Alaska’s governor, and the Bering Straits Native Corporation.

The project isn’t near a salmon fishery, and it has the backing of local communities. Nome, Alaska, has a long history of resource extraction.

Two Department of Defense grants have been awarded to Graphite One, one for $37.5 million, paying 75% of the cost of the Feasibility Study.

The company plans to invest $435 million to build a graphite product manufacturing plant in Trumbull County, Ohio, between Cleveland and Pittsburgh. The plant will use synthetic graphite until natural graphite becomes available from Graphite Creek.

Politicians like Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski realize the benefits of mining and processing graphite domestically. Unlike current suppliers like China, which can turn off exports at the slightest provocation, and Mozambique, where civil unrest has interrupted graphite production.

The Graphite Creek mine is in the US; therefore, it faces no tariff or other trade impediments.

Anthony Huston and his team at G1 should be congratulated for single-handedly eliminating US dependence on graphite imports. This is a major accomplishment that cannot be overstated.