- Odd Outcomes

- Returning Trends

- Demand Suppression

- Playing Games with CPI

- Home Again, Warm Again

In stock investing there’s a management style called “growth at a reasonable price” or GARP. It seeks to achieve steadier results by avoiding both expensive growth stocks and beaten-down value stocks.

We can apply a similar idea to economic growth. Everyone wants the benefits of higher GDP. How much inflation, unemployment, and market losses are “reasonable” for the price? When the economy and markets are booming, most people tend not to worry about the price. And sometimes lunch really is free. Not normally and certainly not often, but occasionally the stars align.

Right now, some economists—not a majority but more than a few—think the Fed can deliver a “soft landing.” That would mean inflation drops to a more tolerable level, unemployment doesn’t rise much from today’s historic lows, and a mild recession, if one happens at all.

Possible? Yes, it’s possible, but I wouldn’t call it likely. I expect a real recession soon. It will be different and probably less painful than the Great Recession, but still hurt. And yet… I have to hesitate. So many other people have that same expectation, and I don’t like being in the crowd.

Is a soft landing more likely than most of us think? Maybe so. Today we’ll review the latest data and think about where this is all headed. First, let me again direct your attention to my longtime friend Keith Fitz-Gerald’s Morning! 5 with Fitz letter. He does a tremendous job filtering out the noise and showing his readers how to take advantage of the market as it exists, not as we want it to be.

Reading Keith has made me smarter in recent months, and I’m confident it can do the same for you. Click here to learn more about Keith’s work.

|

Inflation like we’re seeing now hasn’t burned its way through the American lifestyle in over 40 years... but smart investors are using this approach to outpace inflation and safeguard their money. |

This week’s GDP report showed 2.9% annualized real growth in Q4, about as expected. That sounds pretty good and will be good if it continues. But that’s not a sure thing.

I want to repeat a point about GDP I made back in November (see Recession Thoughts). Apart from whether the GDP numbers are right—which is another discussion—the way they’re presented can be highly misleading.

Here’s what I wrote then:

“On October 27 when the Commerce Department released the Q3 advance estimate, the headlines said GDP was growing at a 2.6% annualized rate. But using the numbers above, growth in the last year was 1.8% (from $19.673T to $20.022T est.). What happened?

“The answer is that headline GDP is reported as the current quarter’s growth, annualized (and seasonally adjusted, but we’ll ignore that for now). The change from the preceding quarter was 0.64%. Compound that to four quarters and you get 2.6%. But that is not what actually happened.

“On the surface, you might look at the 2.6% and think 2022 could still be pretty good. It won’t be.

“This year’s first three quarters saw real GDP grow from $20.006T to $20.022T, a difference of 0.08%. If the Q3 estimate holds up and Q4 is about the same, we are looking at something like a 0.7% year. Maybe 1% if we’re lucky. That’s not recession territory, but it’s hardly a boom.”

Applying subsequent revisions, the latest data (which will be revised) shows real GDP growth from Q4 2021 to Q4 2022 was 0.96%, a bit more than I expected. We got lucky. But remember, inflation depressed this number. Nominal GDP rose 7.3% in 2022. Inflation had a giant impact.

(Note: The GDP inflation adjustment isn’t any of the standard benchmarks. It’s something else used for this purpose due to technical reasons we need not explore. Not a conspiracy, just math.)

This distinction between real and nominal GDP will be important this year because inflation has been swinging around so much. If, hypothetically, economic growth holds exactly at the current rate while inflation falls, real GDP could improve a lot even with no additional growth.

Other odd outcomes are possible, too. Falling inflation could mask weaker GDP growth that might otherwise point to recession. Or—more likely, in my view—inflation will fall but growth will fall even more. That gap could easily turn negative and eventually signal recession. But as I have written several times over the past year, it will be a weird recession. GDP, consumer spending, etc., will be suppressed if not negative while I expect unemployment to remain relatively benign compared to past recessions, for reasons I've explained.

The Federal Reserve’s policymakers might actually celebrate that outcome. Remember what they’re doing, and why. The goal is to reduce inflation. The tools are higher interest rates and quantitative tightening, which raise the cost of capital, eventually suppressing aggregate demand and bringing inflated prices back down.

That’s the theory and it usually worked in the past—though not quickly. Waiting to start the process, as happened in the 1970s and again in 2021‒2022, doesn’t help. This cycle is also different because it sprang from a pandemic and then a war, neither of which the Fed is equipped to control.

Fed policy is definitely having effects. But larger forces are at work, too, and many of them aren’t new.

As Over My Shoulder members (whom you should join, by the way) often see in the charts and other analysis we send, “return to pre-COVID trend” has been a common observation lately. All kinds of indicators had huge swings in 2020, spent a couple of years recovering, and are now back where the previous trajectory would have put them without the COVID interruption.

In one sense, that’s good. It shows how the global economy can repair itself even after such unprecedented havoc. But many of those previous trends weren’t going in helpful directions.

Entering 2020—I know, seems like ancient history now—we were looking at stagnant growth, policy confusion, a labor shortage, excessive public and private debt, and rising international trade barriers. All those are back, some never left and, in various ways, all are getting worse. Add inflation and it’s hard to say we are in better shape now. At best, we have returned to conditions that weren’t great.

Having said that, the economy as of January 2020 wasn’t collapsing, either. We were sort of gradually sliding downhill, which at the time I expected would continue. I wrote a two-part letter that month called “Decade of Living Dangerously” (Part 1, Part 2). I didn’t anticipate COVID or the Ukraine War, but rereading those letters now, they hold up quite well.

In sum, I expected a decade of mild but generally positive growth, interrupted by occasional recessions. Three years into it, that’s exactly what we’ve had. Real GDP rose a total (not annualized) 5.1% in 2020‒2022, including wild swings in both directions and one deep but mercifully quick recession.

The core problem is still the same: Our entire economy is built on staggering amounts of debt. Debt isn’t always bad. It can even be wise when used to create new productive capacity. But even then, there are limits to what we can sustain. Lacy Hunt tracks what he calls the “marginal revenue product of debt,” basically the amount of GDP generated by each new dollar of debt. It’s been falling steadily, which is why we keep needing more debt to produce the same amount of growth.

Needless to say, this isn’t sustainable. We’re going to have a giant debt reckoning at some point. I think it is already beginning. Much of the 2021‒2022 “growth” was really just debt expansion: government debt distributed in various benefit programs, corporate debt subsidized by low interest rates, mortgage debt the Fed took onto its own balance sheet.

These weren’t free lunches. The bill will come before we finish digesting the meal.

I noted above the Fed is using higher interest rates to suppress aggregate demand. I regret to inform you: It’s working. To understand how, let’s follow the process.

“Demand” ultimately means consumer spending. The average person doesn’t buy whole factories or fleets of trucks. But the trucks and factories are links in the chain that ends with a regular person buying a good or service.

That means anything which reduces consumer spending is a problem for the entire economy. Or, more happily, anything that enables consumer spending is good for the entire economy. Sending every household sizable stimulus payments had that effect in 2020 and 2021. Both political parties wanted to boost consumer spending, and they got it. Assorted other fiscal programs helped, too, as did the Fed.

Ever see one of those pictures of a python with a giant bulge as its most recent meal travels downstream? That’s kind of what we did to the economy after COVID. We were in a situation not unlike the hungry snake, who might not really want the whole pig but has no better choices. The stomachache is preferable to going hungry.

Now the economy is reaching the stomachache phase. We’d like to eat more but we just can’t right now, thank you. That’s a problem for those with products to sell, particularly when they borrowed money to make those products. A problem for their lenders, too.

But that’s just the beginning. A substantial part of consumer spending is debt-financed. It’s not just the folks who use payday loans to buy groceries and liquor. The far bigger issue is the people, often well-paid professionals, who incur large amounts of debt to buy expensive cars and homes. Rising rates make this more difficult.

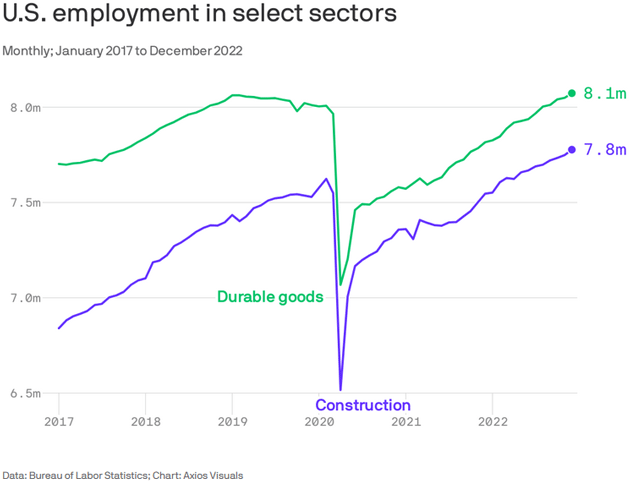

And yet, I have to admit the effect is unfolding more slowly than I would have guessed. Here’s a chart showing US employment in durable goods and construction—both sectors whose customers usually finance their purchases. If higher rates are going to suppress demand, we should see it here first. So far, we don’t.

Source: Axios Macro

The actual number of jobs here is less important than the fact the numbers are still growing. That says employers in these sectors continue seeing plenty of demand despite the Fed’s best efforts to kill it.

Yet like that python, the Fed can keep squeezing until it achieves the desired result. Many analysts expect it to slow the pace again with “only” a quarter-point hike next week. Powell’s team is pretty adept at signaling these moves, so I won’t disagree. I will, however, question whether it means what many think.

I get tired of saying this, but someone obviously needs to:

- “Hiking at a slower pace” is not the same as “pausing.”

- “Pausing” is not the same as “cutting.”

Higher interest rates keep working even after they stop rising. The longer they stay high, the more economic activity they suppress, the more loans get reset at less manageable levels, and the more cash that would have gone into consumer spending goes toward debt service instead. All this adds up and will keep adding up for a long time—possibly years.

This should be obvious but I think it is not sinking in for many investors. Say fed funds reaches 5-5½% this spring, and then stays there for the rest of the year. Then what? What is the effect on consumer spending, corporate earnings, and stock prices? (Hint: not good.)

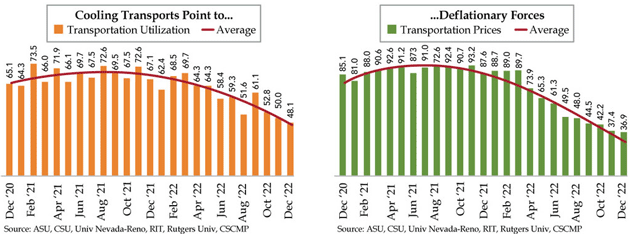

It is already in progress, slowly but surely. Check out these charts from Danielle DiMartino-Booth’s Quill Intelligence letter.

Source: Quill Intelligence

The left chart shows an index of transportation capacity utilization, and the right one transportation prices. Both peaked in mid-2021 and are now considerably lower.

As their headline says, this points to deflationary forces beginning to rise. At some point it should reduce inflation enough to let the Fed cut rates again. How long will that take? We don’t know, nor do Fed leaders. They’re “data dependent,” as they frequently remind us.

This brings us back to that balance between GDP growth and inflation. Both are moving targets. The transport data suggests less stuff is being shipped, which would point to lower growth and, in due course, lower inflation. But inflation depends on other things, too, like energy prices.

If we get in a situation where consumers are paying more to borrow money and paying more to fuel their vehicles and heat their homes, will it be recession? Officially, maybe not. But it certainly won’t be comfortable.

I was surprised this morning to read from my friend Peter Boockvar that he is now going to favor PCE over CPI as an inflation measure. Having had dozens of conversations along this line with Peter that was quite an abrupt shift. Then the explanation follows:

“My readers know I've always preferred the CPI over the PCE, in contrast to the Fed, in giving a more accurate measure of inflation because of the higher allocation to housing that matches reality and healthcare costs that are not price fixed by Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates. Well, for the next 12 months that is going in reverse because of what the BLS announced a few weeks ago with CPI. Beginning with the January print seen in February, the ‘BLS plans to update the spending weights in the calculation of the CPI every year instead of every 2 years. Spending weights indicate what share of total expenditures each item represents.’ They claim that ‘This change will improve the relevance of CPI spending weights by using the most recent consumer spending information. By improving the relevance of spending weights, BLS can improve the accuracy of the CPI.’

“Maybe so but because the comparisons are very high using just one year, the CPI figures over the next 12 months will come in lower than otherwise. In the press release the BLS literally said ‘we hope you will love’ the new ‘improvement’ but making this vital economic stat no longer apples to apples for the next 12 months, I don't really love it but the Fed will because it will make this inflation gauge lower than it would have been.

“So, the PCE, which the Fed in fact prefers anyway, will be the apples-to-apples inflation gauge starting with next month's print, not today's. Just an FYI.”

Without getting into the weeds, for the next year and maybe more, year-over-year comparisons on different segments of the inflation constellation are simply going to look better, or that's the theory. As Yogi Berra said, “In theory, it works. In practice it doesn't.”

Energy prices have helped reduce headline inflation recently. As readers know, I am working on a series of white papers on energy and I think those year-over-year comparisons by the time we get into the third and fourth quarter are not going to be as favorable for energy as the Fed might like. Two quick charts and some comment.

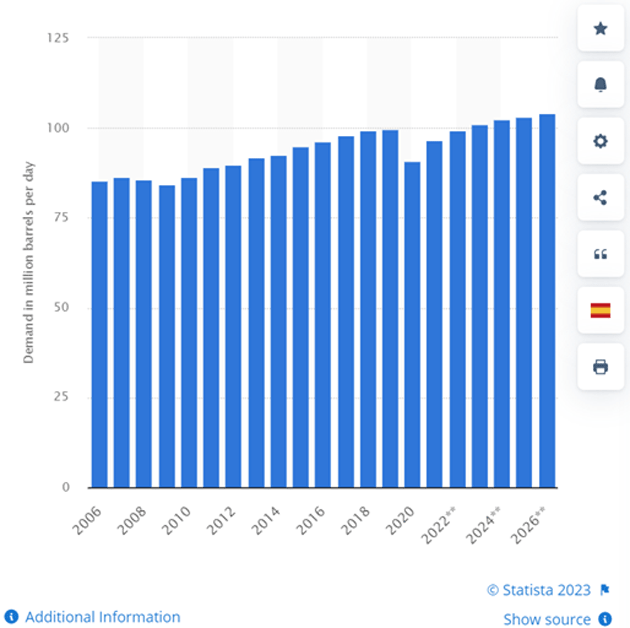

First, demand was suppressed dramatically in 2020 due to the recession. Perhaps more than in previous recent recessions, but demand has always come back and increased over time. A growing world has a growing need for more energy. So the Fed got a “two-fer.” Both demand and price went down for a period of time, even with the Ukraine war.

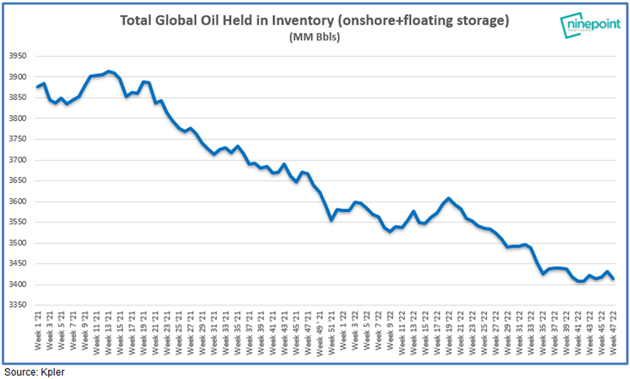

What happened? China shut down, reducing demand by over 1 million barrels a day, while the US and other countries released oil from their strategic reserves. Demand this year will be higher than it was in 2019 as China comes back online and the SPR releases are ended. Inventories are down as is production.

This chart shows daily demand for crude oil worldwide from 2006 to 2020, with a forecast until 2026 (in million barrels per day).

Source: Statista

Source: Ninepoint Partners

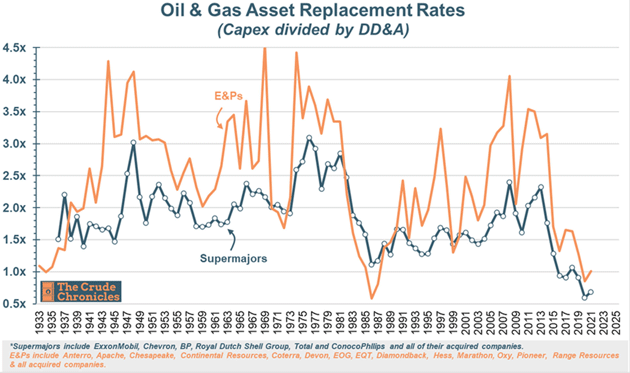

Notice in the chart below that both the oil giants (supermajors) and midsized oil and gas public companies are barely replacing their current falling production with new production, even as the Biden administration asks them to produce more oil. It's a longer story, but many public companies not only have pressure from board members and institutions to reduce production (the whole ESG/climate change environment), but for many companies the market is undervaluing any new production. If you are a CEO, the markets reward you for buying your own shares at a discount to their net NAV. Consequently, we see less projected capital expenditures for new production.

Source: The Crude Chronicles

When demand rises more than supply, prices go up. Demand is going to increase even more as China opens and even more as we get past the current recessionary period. It always does.

And while the year-over-year comparisons may be beneficial for a while, I think rising energy prices will be an inflationary force by the end of this year and into 2024. Same with transportation and other major industries. As Peter noted, markets will be expecting that “pause or pivot” sooner rather than later. I do expect a pause this year but I am not convinced that inflation is going to fall into the under-3% range giving the Fed some room to possibly cut rates.

It all falls into my “weird recession” viewpoint. The Fed is essentially being forced to raise rates in a soft economic environment in order to combat inflation, and by the time they can declare victory, the economy will be growing faster, and they will have to worry about overheating the economy and bringing back inflation if they cut rates.

That is just one potential scenario. I can posit three or four different ones, all with a different set of assumptions. My friend Dr. Ed Yardeni thinks we have been in a “rolling recession” (we had one of those in the 1980s), where different sectors experience negative growth (like housing, transportation). Consumer spending was quite soft in the 4th quarter (where was Santa Claus?) and over half of the Q4 rise in GDP was inventory building, as manufacturing and retail businesses both assumed stronger consumer spending. That inventory build will drag on growth during the rest of the year as inventories fall.

We analysts like to look at scores of data points (often as confirmation of our biases and theses), but there are really only three to watch that are important: inflation, unemployment, and credit market liquidity. Those are what the Fed is watching.

I think rates will stay higher for longer until unemployment gets over 5%. And if it doesn’t because of a relatively tight labor market? And then the recession/slowdown goes away? And the markets will ask for rate cuts during a growing economy?

Without a collapse in employment, the Fed will keep on inflation watch. Which means we might possibly get back to positive real rates and “normal” credit markets and a business environment that doesn’t rely on extremely low rates and debt (financialization) for growth. And it can’t come too soon!

I was in Dallas this last week to do a series of videos for the new oil fund we are developing, as well as finalize a lot of details. We are pioneering a new way for “retail” (as opposed to institutional) investors to benefit from tighter energy markets more directly. I am really quite excited to be involved in something that will change a portion of the energy space. We are quite close to an announcement. But it was cold, at least compared to Puerto Rico. Shane gets in tonight from Boulder, Colorado, where it has been even colder.

It was good to see Tiffani and granddaughter Lively. Lively is 12, but almost as tall as Tiffani (6 feet) and seems to add a few inches every time I see her.

When all my kids were young, we took two trips on “The Big Red Boat,” the Disney cruise. They still talk about it. Daughter Amanda and Allen took their daughters this last week, and now the other kids are clamoring for a larger family cruise trip and then a few days in Orlando. Given all the spouses and grandkids (12 and 8.5 grandkids) and looking at the higher prices, I just smiled and realized we are going to need to drill a LOT of oil to make that dream come true, LOL.

And with that it's time to hit the send button. Have a great week and spend some of it with family and friends! And don't forget to follow me on Twitter.

Your thinking we once again Muddle Through in 2023 analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.