Years of neglecting its critical metal supplies is catching up with the United States, as demand for the raw materials needed to build a new green economy that rejects fossil fuels gears up.

US President Joe Biden just announced a $2.3 trillion infrastructure spending package aimed partially at shifting the US transportation system from gas and diesel-based to battery-powered, and more support for renewable energies such as wind and solar over carbon-based sources like natural gas.

The plan is big on promises and appears to benefit many sectors, but details are scant on how the country will source the metals needed for repairing and replacing traditional “blacktop” infrastructure, and minerals that will feed a brand new “mine to battery” supply chain.

This article takes a deep dive into the US metals problem and how it might work with its northern neighbor to address it.

$2.3 trillion for infrastructure

Biden’s long-anticipated infrastructure build-out finally became public knowledge this week. The $2.3 trillion spending proposal, announced Wednesday, is aimed at making the United States more productive by for example investing in public transportation to make it easier for Americans to commute to work, and rural broadband that improves workplace technology.

It focuses more on long-term goals as opposed to the recently passed $1.9 trillion covid-19 relief bill, underpinned by economic recovery, and getting people back to work. Funding will be over eight years.

Out of $621 billion allocated to transportation infrastructure, $174B will be made available for helping companies to make electric vehicles, and to build 500,000 charging stations across the country. Biden’s proposal also calls for shifting the federal fleet, including the Postal Service, to fully electric vehicles, and mandating that federal buildings only use clean energy sources.

A new “clean electricity standard” would force utilities to wean themselves entirely from carbon-emitting sources by 2035.

The plan also calls for $100 billion to improve the electrical grid system, including construction of higher voltage transmission lines, made up of copper or aluminum.

Mining over oil

What does Biden’s $2.3T infrastructure package mean for US mining? The president has said he supports domestic production of metals needed to make electric vehicles, solar panels and other green technologies, and reportedly backs bipartisan efforts to foster a domestic supply chain for lithium, copper, rare earths, nickel and other strategic materials that the US imports from China and other countries.

On the other hand, the Democratic Party has up to now been no friend to the mining industry. During his campaign for president, Biden was firmly against dropping the ban on uranium mining close the Grand Canyon, and on his first day in office, shut down the Keystone XL pipeline that, part-way through construction, was being built to send Alberta oilsands crude to US Gulf Coast refineries, thereby relieving the glut of oil in North America that has been depressing the price of Western Canadian Select. Allowing the pipeline to go ahead would have been a major boon to Canadian producers.

Will Biden take a similar approach to new mining projects that could adversely affect the environment? It seems likely the left-leaning president would defer to his environmentalist base, rather than risk losing their support, even though, ironically, the exploration for and extraction of battery and energy metals is necessary for advancing his climate agenda.

In-demand metals

More clean energy means more solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and lithium-ion batteries, both for EVs and grid-scale storage. For some materials, like silicon, supply is plentiful, but for others, such as the rare earth neodymium for wind turbines, lithium, cobalt, graphite and nickel for batteries, and copper for just about everything involved in wiring, the supply chains will need to shift.

That’s because for most of the metals used in clean energy and electrification, the United States relies on imports.

Since the days of Donald Trump’s presidency, the US has been planning to reverse its dependence on foreign rivals especially China, which currently has the largest EV market and dominates the global battery supply chain.

Under an executive order issued by Trump, a report was published by the Interior Department in 2018, highlighting 35 minerals that are critical to the US national and economic security, 14 of which are 100% dependent on imports.

The current president, too, is aware of America’s vulnerabilities. In late February, the Biden administration announced it would conduct a government review of US supply chains to seek to end the country’s reliance on China and other adversaries for crucial goods.

For example, about 85% of the world’s neodymium is concentrated in a few Chinese mines, and most of the world’s cobalt production comes from the politically unstable Democratic Republic of Congo.

This would be a natural step to take should the US wish to achieve its ambitious climate goals, and many, including those on Wall Street, are predicting that a change in US administration will finally set off a battery boom. About 30% of an electric car’s cost goes towards its battery, which requires metals such as lithium, graphite, and cobalt – all on the US critical minerals list.

A glance at the US Geological Survey’s mine production data, shows how little of these materials the United States mines.

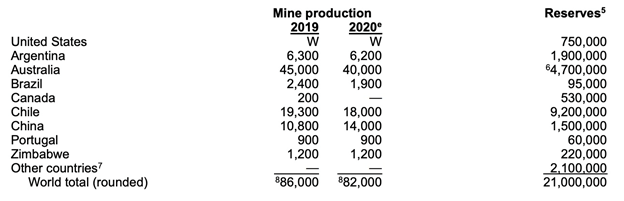

For example, in 2020 (and earlier) the only lithium production in the United States was from Albemarle’s Silver Peak brine operation in Nevada. While the actual amount was withheld by the company, it certainly comes nowhere close to the top three producers, Australia (40,000 tonnes), Chile (18,000t) and China (14,000t). As for current identified lithium resources, the USGS notes these have increased substantially due to continuing exploration, but out of the 86-million-ton total, only 7.9Mt has been found in the US, and 2.9Mt in Canada.

No natural graphite, needed to make spherical graphite used in the EV battery anode, was mined in the US in 2020. The world’s inferred resources of recoverable graphite exceed 800 million tons, but domestic sources are “relatively small,” states USGS.

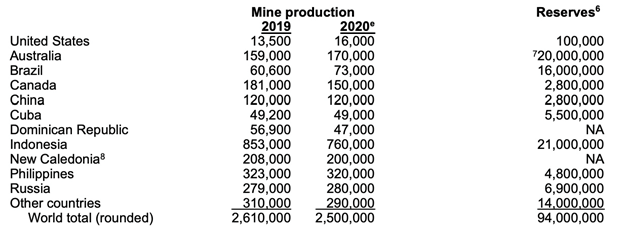

US mines only produced 16,000 tonnes of nickel last year compared to 760,000t in Indonesia, 320,000t in the Philippines, and 280,000t in Russia, the top three Ni miners. Canada managed to output 150,000 tonnes.

It’s hard to imagine the US being able to fulfill its new clean energy agenda without either a significant increase in critical metal imports that frankly may not be possible in current market conditions or executing a home-grown strategy to explore for and mine them in North America.

2020 world lithium production. Source: USGS

2020 world lithium production. Source: USGS

2020 world graphite production. Source: USGS

2020 world nickel production. Source: USGS

2020 world nickel production. Source: USGS

Copper crunch

As we at AOTH have written, among all of the metals, none is more critical than copper, even though the red metal is never categorized as such.

Mainstream media and the large mining companies are finally catching on to what we have been saying for the past two years: the copper market is heading for a severe supply shortage due to a perfect storm of under-exploration/ lack of discovery of new deposits, clashing with a huge increase in demand due to electrification and decarbonization.

Yet it appears the US did not get the memo.

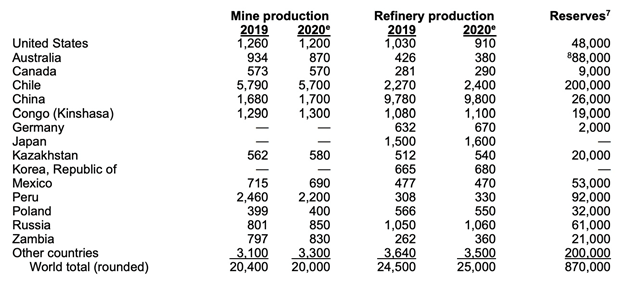

It is interesting to note that, even though in 2020 copper exports to China were surging, along with prices, as the country sopped up millions of pounds of cheap copper rendered less expensive by the pandemic, in the United States copper production actually fell. According to the USGS, output decreased by 5% to an estimated 1.2 million tons. (about a fifth the production of top producer Chile)

2020 world copper production. Source: USGS

2020 world copper production. Source: USGS

One of the problems with copper is it’s difficult to find in large enough amounts close to surface, where it’s economical to extract. It also takes many years to bring a copper deposit into production, especially in places like the United States and Canada where miners face strict permitting regulations that can cause delays. According to Bloomberg Intelligence, the average lead time from first discovery to first metal has increased by four years from previous cycles, to almost 14 years.

Recent research by BI reveals the mining industry needs 10 million tons more copper to meet much higher demand from the clean power and transportation sectors.

To do so requires spending up to $100 billion, to head off what could be an annual supply deficit of 4.7Mt by 2030, according to estimates from CRU Group. The shortfall could rise to 10Mt, per year, if no new mines are built. Closing the gap would mean the equivalent of building eight new copper mines the size of Chile’s Escondida, the biggest in the world.

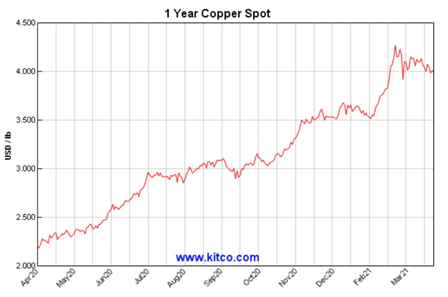

Failure will be measured in the price of copper, which is bound to go up, subject to the natural laws of supply and demand.

“Increasing technical complexity and approval delays could lead to a dearth of shovel-ready projects in 2025-30,” Bloomberg Intelligence analysts Grant Sporre and Andrew Cosgrove wrote in a report this week. The authors added:

“After China’s State Reserve Bureau mopped up all of the excess copper from 2020’s Covid-19 slowdown, the market now looks fundamentally tight, with our analysis pointing to at least two years of deficits. With these shortages, alongside investor interest in copper’s decarbonization credentials, we think a price above $8,500 a ton is well supported.”

1-year spot copper price. Source: Kitco

1-year spot copper price. Source: Kitco

Competition from China

One of the reasons Biden is so keen on a large infrastructure spend, including actions to tackle climate change, is to compete with China, whose share of spending on clean tech research and development has outpaced the US.

It’s not only R&D though, where the US trails, but in something more basic, and that is the actual building blocks of a green economy.

The world, as mentioned, is heading for a supply shortage in copper, just as the States is going to need one hell of a lot of it. Will that still be possible, with China moving to lock up supply?

We don’t know for sure, but recent developments are concerning. Data compiled by Bloomberg shows as the rest of the world went into lockdown last year, China went on a copper buying spree. Analysts say the amount of copper imported points to Beijing not only diverting the shipments to industrial use but stockpiling it.

The country imported 6.7 million tons of unwrought copper in 2020, a third more than 2019, and 1.4Mt more than the previous annual record. In fact, as Bloomberg notes, “The year-on-year increase, alone, is equivalent in scale to the entire annual copper consumption of the U.S.”

The disconnect here is astonishing. As US mines slowed their output of the red metal, largely due to crimped demand and lower prices owing to the economic slowdown, China took the opportunity to “buy low”. Traders and analysts quoted by Bloomberg reckon that China’s State Reserve Bureau bought between 300,000 and 500,000 tons during the price slump.

This is nothing new to those who have been following China’s shrewd lock-up of much of the world’s metal.

In the early 2000s, Chinese companies spent about $5 billion buying more than a dozen copper mines and deposits, from Afghanistan to Zambia. In 2007, Chinalco paid C$840 million for the mineral rights to a huge copper deposit in Peru called Toromocho, at the time said to be worth $50 billion. Building the mine meant moving the town of Morococha, pop. 5,000.

Another major Chinese copper buy happened in 2016, when Freeport McMoran agreed to sell its majority stake in the DRC’s Tenke copper project, to China Molybdenum (CMOC) for $2.65 billion — “reducing the US copper miner’s debt but handing the Chinese company one of the world’s prized copper assets,” as Reuters states.

China, of course, already has a monopoly on rare earths mining/ processing, produces the most lithium and cobalt, and dominates the graphite market.

Most observers see the US losing the EV battery race to China and Europe despite the United States making some progress in developing lithium deposits in California, Arkansas and Nevada, and new battery plants being built in Georgia, Ohio and Colorado.

According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, the country’s share of global battery production will fall from 8% currently to 6% in 2025.

This could be a problem for the litany of automakers that are switching gears, so to speak, to EVs. Relying on imported batteries could mean paying more for them, than if they were produced domestically. The logistics are also a challenge, in shipping large, heavy battery packs, which can weigh up to 1,000 pounds each.

“If we want to have a domestic supply chain for batteries in North America, now is the time you have to press the accelerator,” states Sam Jaffe, managing director of Cairn Energy Research Advisors, a consulting company in Boulder, CO. “The conversation should be ‘mine to car,’ not just ‘battery to car.’”

Instead, the Bloomberg article notes, the US has treated security of supply as a peripheral concern.

“China has been looking at vulnerabilities in its supply chain from top to bottom for a while, and growing its strategic reserves,” the news outlet quotes David Lilley, a veteran copper trader. “I don’t think the West has even begun to think about it. There is still a casualness here about raw material supply.”

Casual indeed.

CRU Group estimates a trillion dollars spending on infrastructure could necessitate an extra 6 million tons of steel, 110,000 tons of copper, and 140,000 tons of aluminum annually.

Will the US be able to magically ramp up its copper production by 10%? Or will it have to import more copper at higher prices than if it had done the smart thing and bought/ stockpiled it last year? These are the kinds of questions Washington should be asking.

Canada can help

Fortunately, there is still time, and hope, that the United States and Canada can get it together and put aside some prized metal assets of their own before China and other trade competitors — after all, the whole world is “going green” and wanting access to these commodities — gobble them all up.

In January of 2020, the Canadian and US governments announced the Joint Action Plan on Critical Mineral Collaboration. The agreement would increase production and establish supply chains for numerous critical minerals the US is dependent on for imports.

For example, according to Natural Resources Canada, the country has more than 15 million tonnes of rare earth oxides, including the generally more valuable heavy REEs, that could be developed into mines, to help meet US demand.

Ottawa recently released a critical minerals list like the list of 35 published by the US in 2017 — the difference being that Canada’s list is more like a catalogue than a wish list, of the metals it has in stock and considers essential.

The 31-metal catalogue includes not only cobalt, graphite, lithium, and rare earths, which usually appear in such lists, but copper, nickel, and zinc – base metals thought to be fundamental to building a green energy future.

Earlier this year, the governments of Ontario and Canada announced a plan to each spend $295 million to help Ford upgrade its assembly plant in Oakville to start making electric vehicles.

At the recently concluded PDAC conference in Toronto, Francois-Philippe Champagne, Canada’s minister of innovation, science and industry, told Invest in Canada’s CEO Ian McKay that Canada is uniquely positioned to be a global leader in EV manufacturing.

“Canada offers renewably generated electricity, a skilled workforce, a stable and predictable jurisdiction to operate in, the rule of law – a commodity very much in demand these days – and an abundance of the critical minerals needed for the batteries that power electric vehicles.

“People are now placing more value on supply chains, which are moving from the global to the regional and switching from efficiency to resiliency,” Champagne said. “Canada offers enormous opportunities not just for auto manufactures but the whole ecosystem, with significant investment being made by auto manufacturers and the Canadian government.”

Critics of greater collaboration between the United States and Canada would argue that all we have so far are lists of critical minerals. There is yet no government funding to support exploration. However, Canada’s minister of natural resources, Seamus O’Regan, told CIM magazine recently that establishing the list in an important step for Canada, especially as it can send a message about the country’s intentions and priorities, especially reaching net zero emissions by 2050, to investors.

O’Regan notes Canada already supplies 13 of the 35 minerals on the US list, “and we have the potential to supply more.”

PDAC President Felix Lee also weighed in, telling CIM:

“It’s important to remember that here in Canada we are an enormous country, and the mineral wealth is incredible, and a good part of it remains untapped. The critical minerals list really gives us a chance to start to focus our geoscience programs, our government geoscience programs, on those minerals and metals that count…Not only can we inform our geoscience programs, we can also further inform our land-use decisions through the use of this list. Plus, if we have an idea where certain minerals and metals exist, we can drive everything else.”

Empty platitudes? Maybe. But at least critical minerals and supply insecurity are now on the US and Canadian governments’ radar, after being off it for decades.

Our mineral exploration sector doesn’t need public money to succeed in finding new deposits that will go a long way towards addressing global supply shortages but having government on side during the often-long road from discovery to production can certainly help with permitting new mines, as demand for green energy/ transportation metals goes bonkers.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.