Could arguably the world’s worst currency become its best?

If Zimbabwe follows through and embraces a plan to back the Zimbabwe dollar with gold, it just might.

Last week, Zimbabwe President Emmerson Mnangagwa said officials were exploring ways to introduce a "structured currency,” but he didn’t explain what that meant. On Monday (Feb. 12), Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube shed some light on the plan, saying the goal was to “manage the growth of liquidity which has a high correlation to money supply growth and inflation.”

The way to do that is to link the exchange rate to some hard asset such as gold. To do that you have to have some sort of currency board type system in place where the growth of the domestic liquidity is constrained by the value of the asset that is backing the currency.

The Zimbabwe dollar has lost more than 40 percent of its value just since the start of the year.

Consumer prices in Zimbabwe rose 34.8 percent in January on an annual basis. That was up from 26.5 percent in December, according to data released by the Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency.

Those numbers don’t reflect the full extent of Zimbabwe's currency devaluation since about 80 percent of transactions occur in U.S. dollars. The government changed its CPI calculation last fall to better reflect the presence of the dollar in the economy. In other words, it "updated" its inflation formula to hide the extent of the problem. The U.S. government did the same thing in the 1990s.

This isn’t Zimbabwe’s first foray into the world of inflation. As Business Insider Africa put it, “Zimbabwe continues to bear the scars of hyperinflation endured during the extended leadership of Robert Mugabe.”

Hyperinflation wiped out the value of the Zimbabwe dollar in the early 00s. In 2009, the government simply abandoned its own currency and adopted foreign currencies – primarily the U.S. dollar (or, more accurately, the Federal Reserve Note).

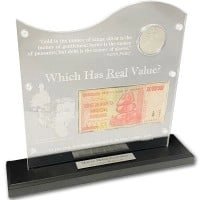

Silver versus Zimbabwe Dollar Display

The African nation reintroduced the Zimbabwe dollar in 2019. But the government apparently didn’t learn its lessons and the currency quickly devalued again. By mid-July 2019, price inflation had increased to 175 percent.

As economist Milton Friedman once said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

In other words, if a country is experiencing price inflation and currency devaluation, it is ultimately the government’s fault. Price inflation is a symptom of monetary inflation – government creating more and more currency to prop up spending.

During Zimbabwe's first round of hyperinflation, the government was printing money to finance Mugabe’s military involvement in the Congo. It was also allegedly creating currency to pay for government corruption and to fill the pockets of politicians and their buddies.

More recently, Al Jazeera reported, “The printing of new money by the central bank has also worsened the situation, reversing gains made in the past two years that saw inflation decrease from a peak of 800 percent in 2020 to 60 percent in January [2023].”

The Zimbabwe government has already taken some steps attempting to stabilize its currency and limit its dependence on the Federal Reserve note dollar.

Last summer, Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe Governor John Mangudya announced Fidelity Gold Refineries (Private) Limited would mint gold coins and make them available to the public through the country’s banking institutions.

The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) resolved to introduce gold coins into the market as an instrument that will enable investors to store value.

The central bank owns Fidelity Gold Refineries (Private) Limited. It operates as the only gold-buying and refining entity in the southern African country.

In October, the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe launched a digital payment system backed by physical gold.

The digital tokens called Zimbabwe Gold (ZiG) can be stored in a digital e-gold wallet or on e-gold cards. An equivalent amount of physical gold held in the RBZ’s reserves backs each digital token. Individuals and businesses can use ZiG in business transactions and can share the gold-backed tokens peer-to-peer. In practice, this gold-backed digital currency makes it possible to do everyday business in gold.

The hope was this gold-backed payment system would ease the pressure on the country's limited supply of dollars (and create of flow of dollars into government vaults.)

Putting the Zimbabwe dollar on a gold standard would slam the door on the Zimbabwe government’s inflationary policies. Backing currency with a hard asset limits money creation. The government can’t create more dollars unless it gets more gold. A gold standard puts a natural brake on monetary expansion.

This would benefit Zimbabweans who would enjoy a stable currency and could maintain their purchasing power over time.

Of course, that requires fiscal discipline on the part of the government. It can’t rely on money printing to support its spending. Therein lies the rub. Government people tend to quickly abandon any pretense of linking the currency to gold when they discover it puts the kibosh on expanding their power.

With this in mind, I’m skeptical that Zimbabwe will follow through with reforms. As Money Metals Exchange President Stefan Gleason put it, “Sadly, total catastrophe may be the most likely path to reform. The only danger is that with the wrong people in place, the catastrophe could lead to a lurch towards tyranny.”