Don’t Tax You. Don’t Tax Me. Tax That Fellow Behind the Tree

- Attributed to Senator Russell B. Long, Louisiana ~1930s

One thing you learn when writing about the debt problem, as I have been in recent weeks, is that many people think it’s not a problem at all. They believe we could easily balance the budget by (insert simplistic idea here).

It’s scary to think some problems are so big we can’t even understand them, much less solve them. Convincing ourselves the solutions exist but are being ignored provides some mental comfort. It lets us blame some nebulous “they” instead of taking responsibility for our own part of the problem.

In my October 27 Debt Catharsis letter, I talked about the difficulty of balancing the federal budget with only spending cuts or only tax increases. Those paths are closed now. That’s one consequence of waiting too long; the available options grow narrower and more difficult.

Yet people continue to say we could balance the budget and pay down the debt by (for instance) “making the rich pay their fair share.” I wish it were that easy. I really do. But sadly, as I’ll show you today, it’s not.

Part of the problem is we have to define what it is to be “rich” and then what is “fair share.” As it turns out, that is not easy.

The US income tax system is designed to be progressive, meaning the percentage owed rises as income rises. For a long time, it was so progressive that only the very wealthy paid anything at all. That’s not the case now, but the wealthy still pay higher percentages of their income.

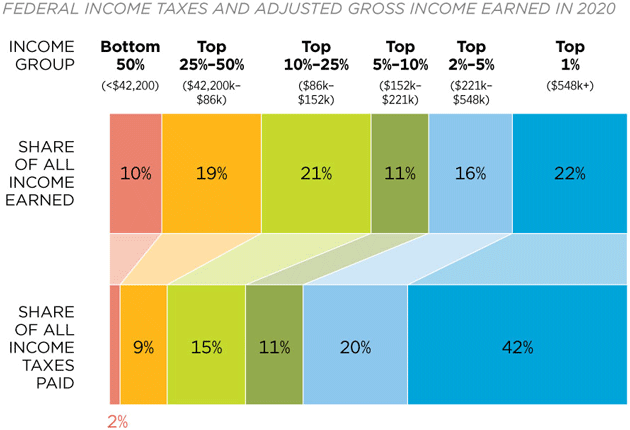

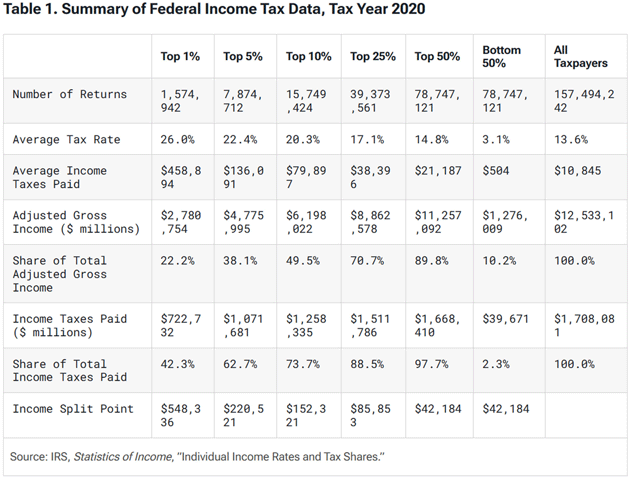

That’s the case not just individually but across the population. The IRS publishes distributional data on this. Here’s how it looked in 2020 (latest available).

Source: Heritage Foundation

In this year (which is typical), the top 1% of taxpayers collectively earned 22% of the total adjusted gross income and paid 42% of the total taxes. The next 4% had 16% of AGI and paid 20% of the taxes. Below that, tax paid is proportionately the same or less than earnings.

If the goal is for the wealthy to pay the most, that’s what is happening. The top 5% pay a larger share of the taxes than their share of income—almost twice as much for the top group. Meanwhile the reverse is true for the bottom half: Their tax liability is half or less than their share of income.

Combining the top three tiers, we see households representing 49% of the income bear 73% of the tax burden. These are averages so of course you can find exceptions. Personal situations vary, as do tax consequences. But the tax system remains quite progressive, as it was designed to be.

For those who think the wealthy should pay more, I invite you to get specific. Should the top 10% of taxpayers bear 80% of the tax burden? 90%? 100%? If the current 73% isn’t fair, what would be?

But let’s set aside fairness. Would raising the high-income rates actually produce more revenue? That is not at all clear. People, particularly wealthy people, respond to financial incentives. Raising taxes enough to significantly change this distribution wouldn’t necessarily have the desired result.

If we want to balance the budget, whether by spending cuts or tax increases, we first need to know the target. How big is the gap? It’s not an easy question, first because the federal government is so huge and second because its finances are a moving target. The Congressional Budget Office projections assume all current policies will remain in place, which of course they won’t.

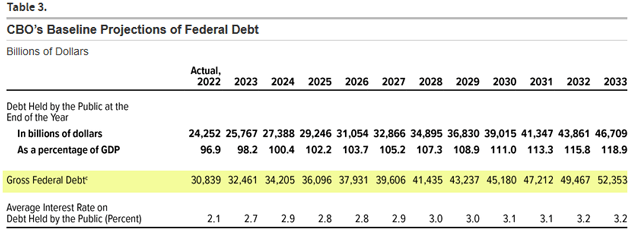

Rather than the annual deficits, which are subject to various manipulations, I prefer to look at the increase in debt. Here are the numbers as of a May 2023 CBO budget update. They are already outdated but close enough for our purposes.

Source: CBO

I highlighted “Gross Federal Debt” because this is the full amount, including money the Treasury owes to governmental trust funds, etc. It is presently around $32 trillion and CBO projects it to reach the $52 trillion area by 2033. That’s almost certainly low, but let’s go with it for now. It means the debt will rise by an average of about $2 trillion yearly for the next decade.

That’s our bogey, then. We need some combination of lower spending and higher revenue adding up to $2 trillion per year… if we start right away. And we’re not, so the target will grow more distant the longer we wait (as I said back in the early part of this century). But for simplicity, let’s stick with $2 trillion. Can we raise it from revenue alone?

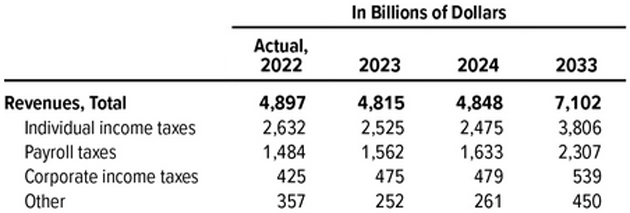

Here is the revenue breakdown from that same CBO report.

Source: CBO

Focusing on 2024, we see individual income tax is about half of total revenues. Payroll taxes are another third. Corporate income taxes and “Other” (import tariffs, excise taxes, etc) are relatively small.

To find an additional $2 trillion in tax revenue, we’d need to increase revenue (i.e., raise taxes) by about 41%. Want to put it all on corporations? Ok, go ahead and quadruple business taxes. Let me know how that affects the economy and especially the unemployment rate.

The amount of revenue needed to balance the budget without spending cuts is so vast, it’s feasible only if spread over a wide base. That means individual income tax and possibly payroll taxes as well. But exactly how it’s done matters.

In that October letter mentioned above, I used a simulation from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget to identify possible tax increases. When I simply checked off every revenue-raising tax change they listed, the result was a $13.7 trillion debt reduction over 10 years, or an average $1.37 trillion per year. That’s still short of our $2 trillion target despite including some giant new taxes: a wealth tax, a carbon tax, a value-added tax, and a bunch more. The whole package would affect everyone, not just the wealthy.

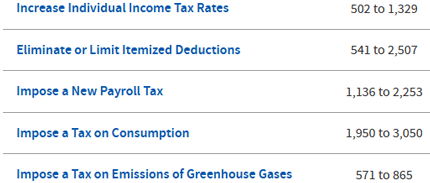

We can also look at official sources. The CBO periodically issues a list of budget options intended to “help inform federal lawmakers” about policy choices that might reduce the debt. These are not recommendations because that’s not CBO’s role. They are things Congress could conceivably do that might reduce the debt. The last edition is from December 2022, just a year ago.

It’s an interesting list—or two lists, actually. CBO publishes it as Volume 1: Larger Reductions and Volume II: Smaller Reductions. Follow those links and you can click on each line item for further explanation. Many have multiple options, so the budgetary effects are often shown as a range. The amount of debt reduction varies depending on the details.

The “Larger Reduction” list includes five possible tax changes.

Source: CBO

Those numbers are billions of dollars in debt reduction over 10 years. If you add up the lower end of the range, it is $4.7 trillion. The combined upper ends are $10 trillion. (These are CBO estimates, which I’m sure the wonks calculate as best they can, but of course no one knows the future. And anything Congress passed would likely differ from these ideas.)

The “Smaller Reductions” report has 23 more ideas which, if all became law and produced savings at the upper end of CBO’s estimates, would contribute an additional $2.8 trillion in debt reduction over 10 years.

In budgetary terms, the best case outcome of Congress passing every single tax increase CBO considers feasible would reduce the debt by $12.8 trillion over 10 years vs. current law. That’s far short of the amount needed to balance the budget. And keep in mind, simply balancing isn’t enough. We’ll need years of surpluses to bring down the existing debt load. Or an inordinate amount of revenue-producing economic growth, which hasn’t happened in any extended manner in this century.

Moreover, these tax increases, if passed, would certainly put millions of voters in a pitchfork-wielding mood. It would mean, for instance, adding a 5% national VAT on almost all goods and services, on top of existing sales taxes in most states. I’ve talked about a VAT as a possible alternative to income tax, or a supplement to allow lower income taxes. That’s not the idea CBO presents here. This would add a VAT and raise income tax rates while eliminating many deductions. Oh, and also raising payroll taxes by two percentage points.

Follow the links above and you can read the ugly details for yourself. Implementing all this would have major side effects and still wouldn’t solve the problem.

When you face a seemingly unsolvable problem, one option is to redefine it. Our appetite for federal spending has now grown so large, and our options to pay for it so limited, that the idea of a “balanced budget” seems increasingly quaint. This has always been the case in the MMT camp, which argues the debt simply doesn’t matter. But a growing number of fiscal hawks are also deciding the goalposts have to move.

For example, the aforementioned CRFB is about as dedicated to fiscal rectitude as any organization in Washington. Its bipartisan board includes names like Erskine Bowles, John Kasich, Alan Simpson, and David Stockman. This is a serious group that knows the stakes. Yet earlier this year, CRFB published what I can only call a note of frustration.

“Balancing the budget has become increasingly challenging over the past 15 years. Efforts to show balance too often rely on unrealistically aggressive cuts, unspecified savings, rosy economic assumptions, and other budget gimmicks as a result. Successful budget actions in recent years have come mainly from more targeted deficit reduction efforts than from trying to meet overly aggressive fiscal goals.

“And with deficits on course to reach $2.4 trillion (6.6 percent of GDP), balancing the budget is now harder than it has ever been…

“[A]achieving balance within a decade is incredibly challenging. Enacting the $7 trillion CRFB Fiscal Blueprint, which puts all parts of the budget and taxes on the table, would reduce the 2032 deficit to 2.9 percent of GDP (down from 6.6 percent) when incorporating stronger economic growth effects – still far short of balance.

“Instead of shooting for balance within 10 years, it would be wise to select a different target or timeline, such as:

-

-

- Balancing the primary (non-interest) budget;

- Reducing or stabilizing debt as a share of the economy;

- Setting a 10-year savings target, such as $7 trillion in deficit reduction or $4 trillion of non-interest spending cuts; or

- Setting a longer time period than 10 years.

-

“Wanting to balance the budget is an admirable and desirable goal. However, the path to get to balance within 10 years is likely infeasible, and it is virtually impossible if major parts of the budget and tax code are exempt from change. Policymakers should set aggressive but realistic fiscal goals, should keep all areas of the budget on the table, and should put forward policies to begin reducing deficits.

“The first step, of course, is to avoid actions that would worsen our already unsustainable fiscal situation. Policymakers should agree not to pass legislation that calls for any new borrowing. We commend the adoption of a specific and realistic fiscal target.”

Again, this is a group of well-informed budget hawks concluding that a balanced budget within 10 years is practically impossible. They aren’t giving up on the goal. They’re rightly recognizing it is an incredibly tough problem that gimmicks and rosy assumptions won’t solve.

I keep saying that balancing the budget with just tax increases won’t work, but let's assume that Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are right: The rich don't pay their fair share. So, let's double down on that. Raise income tax on “the rich” by 50%. How much would that help erase the deficit?

That would mean the top tax rate going from 37.5% to 55.25%. plus state and local income taxes, plus Medicare at almost 4%. In some states the combined top rate would be roughly 73%. How much would that raise?

It turns out those helpful people at the Tax Foundation, using data from the IRS in 2020, can make some close approximations. Look at this table then we will go into details.

It turns out the top 1% paid $722 billion in taxes. Raising that by 50% would give us another ~$361 billion, give or take. That only gets us 18% of the way there. By the way, under this definition you would be rich if you made over $548,000 a year.

Let's expand it to the top 5%, who paid $1.07 trillion. Raising that by 50% would give us an extra $500 billion, which sadly only gets us to 25% of the goal. And that defines everybody who makes over $220,000 a year as “the rich.”

But let's press on. We need more money so let's define rich as the top 10%. Now we are talking about everybody who makes over $152,000. The top 10% pay ~$1.25 trillion. That would give us an extra $625 billion, or roughly a third of the way there. We still need another $1.3 trillion.

In fact, if we raised taxes about 50% on everybody, from the bottom 1% to the top 1%, it would only get us $850 billion or a little less than halfway there. Yes, Virginia, we have dug a pretty deep hole for ourselves. And there is no Santa Claus.

Now, it is true wealthy people have ways to shelter income and tend to have a lot of capital gains, so their actual paid tax rates can be lower than the income tax rates. This is where it gets a little tricky. I can search on “What do the rich actually pay in taxes?” and get a multitude of answers, generally running from about 20% to a little over 30%, depending on who is counting and what models they use. But no matter how you slice and dice it, increasing taxes on the rich will not get us anywhere close to a balanced budget.

Further, it will distort the system in ways that we can't predict. Thomas Piketty, the French economist, argues that the rate of capital return in developed countries is persistently greater than the rate of economic growth, and that this will cause wealth inequality to increase in the future. In general, that is correct. He sees that as a bug in the system. I would argue it is a feature, not a bug. We want to encourage investment and entrepreneurship, as they increase the general welfare for everyone.

Buried in Piketty’s book is a table on how much taxes individuals pay. It generally follows GDP growth, with the exception of 1986, where there was a large uptick in the amount of income that individuals earned. A very large uptick. What happened? Prior to 1986, the top rate on corporate taxes was significantly below the top personal tax rate. A tax bill flipped that. So almost overnight, private companies went from being schedule C corporations to schedule Sub-S corporations. This allowed the income to pass directly through to the individual at the new, lower rates. There was in fact no explosive growth in business or income, it was simply an accounting change.

I know, because I was one of those entrepreneurs that changed my corporation from a schedule C to schedule Sub-S.

(Sidebar: In an era of high personal tax rates (prior to 1986), I don't think I ever paid more than about a 10% effective tax rate other than Social Security. That was because we got so many write offs and ways to deduct things. Ah, the good old days. Part of the tradeoff that Reagan did with O'Neill was to get rid of all those loopholes. So, anyone arguing that we lived through 70% or 90% tax rates and the world was just fine didn't actually live back then and understood how business operated. NOBODY actually paid that top tax rate, unless they were clumsy and had bad accounting advice.)

You cannot argue that the world has not been made better by business and entrepreneurs and be taken seriously. Moses argued the principle that “muzzle not the ox that treaded out the corn.” Entrepreneurs and investors do not risk their capital without some expectation of an above-GDP-market return. Otherwise, they would just invest in government bonds and go on down the road.

Can anyone seriously argue that a 50% tax increase on whatever you call the rich would not be a significant deterrent to growth and investment? What about 25%? 15%? It might make somebody feel good that we are taxing people more, that person behind the tree, but it will seriously slow growth down. See for reference pretty much all of Europe.

Let me just finish by saying the situation is desperate, but not hopeless. We will still need a crisis to actually force the difficult choices, but they can be made. Though at this point it will be at a significant cost to future GDP growth for a period of time. The optimists among us hope that technology of all stripes can overcome that drag.

Shane and I will be staying in Dorado Beach, Puerto Rico, for the holidays. We will be throwing our annual New Year's Day party with black eyed peas and Texas chili, with ~100‒150 of our friends and neighbors. It will be a lot of fun.

I rarely mention anything political because I have readers of all persuasions. My beat is economics and finance, not politics, though most people understand where I reside. But I have been a little bit more active on X (formerly Twitter), and some of that is because of my frustration around the whole Israeli/Hamas situation. I particularly find it distressing that so many students and universities think it is permissible to call for genocide of our friends of a Jewish persuasion and that university officials will tolerate it.

Schools like Penn or Harvard enforce the correct use of pronouns because it is considered abuse to not use the proper pronoun that a person wants to be referred to but cannot articulate in a congressional hearing why calling for genocide, which is what they are saying whether they realize it or not, is somehow acceptable depending on “context.” When Jewish students aren’t safe at our elite schools, then what good are those schools?

I have never met him, but I particularly find Bill Ackman and others like him, who are calling these universities out, reflect my sense of outrage. I would encourage you to read Peggy Noonan’s latest Wall Street Journal column where she wonders why the women's movement has not protested the outright sexual assault and depredation of young girls by Hamas. This wasn't one or two individuals. It was planned from the beginning.

When women's groups aren't outraged by sexual assault and mutilation, when they defend Hamas, they are no longer speaking out for women but have clearly chosen a team and that team doesn't include Jewish women. There is no “context” to justify that. Shame on them!

And with that sober thought, it is time to hit the send button. Enjoy the holidays and don't forget to follow me on X.

Your worried about the future for my grandkids analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.