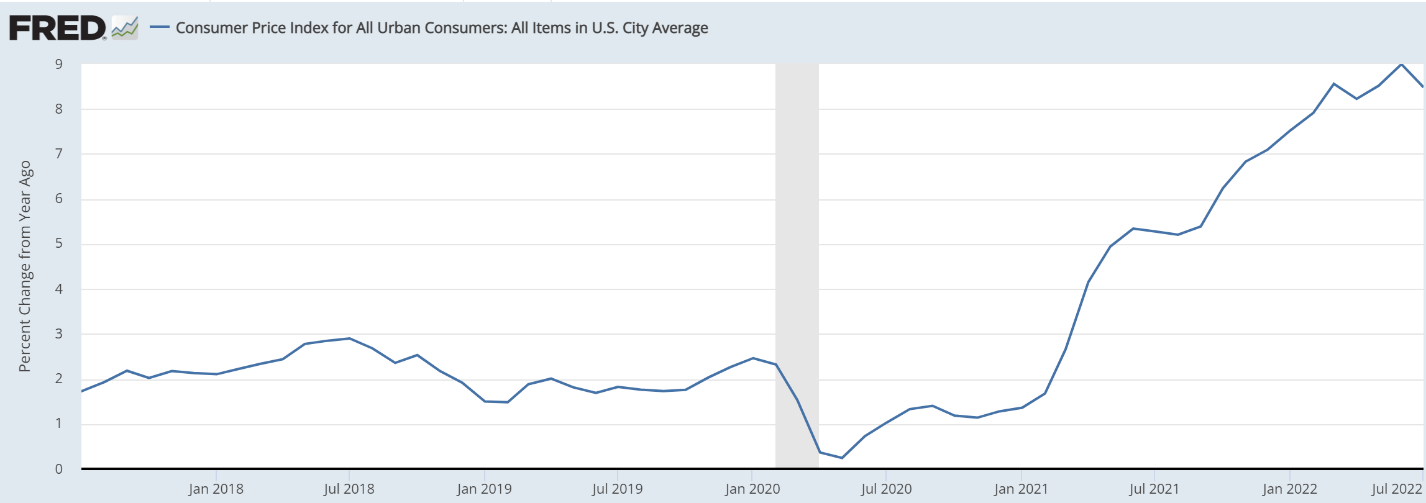

Consumer prices have been on a tear, since early last year. Right now, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is rising at more than 8% per year.

Source: St Louis Federal Reserve

Conventional thinking calls for higher interest rates. It makes this call via two channels. One is its policy prescription. The other is a theory of how market participants will behave.

There is no such thing as a good central bank policy. All central bank actions inflict harm on the people. However, if one’s sole focus were consumer prices, then one should want lower interest rates rather than higher. A falling interest rate is a rising incentive to borrow more to produce more, at lower margins. We have discussed this elsewhere, and so will not repeat our argument here.

The Bond Market is Different

Today, our focus is how market participants respond. When market participants act en masse, they are a much larger force than any central bank (just as every Governor of a Banco De Republica de Banana, to the Swiss National Bank, has learned to their chagrin).

The theory is simple. If prices go up 1%, then the dollar has lost about 1%. So why should market participants buy bonds that don’t earn more than the dollar is losing?

We see something that looks like this behavior in other markets. For example, pipe manufacturers buy copper and sell pipe. If the price of copper goes too high, then they can’t make any money. So they stop buying copper (alternatively, they could try raising their prices, but home builders will increasingly stop buying copper pipe and switch to plastic).

Another example, in the opposite direction, is what if apartment rents go too low? Then developers don’t go through all the work and expense of building more apartment units.

It seems simple enough to apply this to the bond market. Logically, if pipe makers stop buying copper when the price is too high, then for the same reason, investors will stop buying bonds if the price is too high (i.e. interest rate is too low). If pipe makers define too high as the point at which they would lose money, then logically investors should define too high in the same way. The point at which they would lose money.

One difference becomes evident immediately. In the case of copper, the pipe company is buying copper and reselling it (with some value-added work applied). To say it loses money is black-and-white math. Suppose it buys copper at $4.00 a pound, spends $1.00 forming it into pipe, and sells it for $4.50. Then it’s losing $0.50 a pound.

But the bond buyer is different. He is not buying bonds to resell. The concept of loss here does not refer to selling price minus purchase cost. It is something else.

Loss, here, refers to the loss of value of the dollar itself. We will leave aside that there are now huge nonmonetary forces driving up prices, hence there is not necessarily a corresponding loss in value of the dollar for every rise in prices. We will just accept that the dollar loses value, and this loss is incurred by bond holders.

It also incurred by non-bondholders.

There Is No Escape

No matter if you hold cash in the bank, or if you hold Treasury bonds: when the dollar loses 8% of its value, you have lost 8% of your savings. You suffer the same loss either way.

The bondholder’s decision to buy a bond is not like the manufacturer’s decision to buy copper. In the latter case, the manufacturer’s profit or loss is determined by the price it pays for copper. But in the former, the bondholder is not selling the bond at a gain or loss. He is repaid principal and interest. He has a gain of dollars (i.e. the interest paid). It’s just that the dollars he is paid are not worth the same as the dollars he paid to buy the bond in the first place.

Bonds are a different phenomenon than copper.

Still, it is tempting to assume that the same economic forces apply to the decision to buy copper and the decision to buy a bond. If that were so, then the causal mechanism would be the same. And we would observe the same result. And bonds would never be bid above the break-even price[1], as copper is not bid above the break-even price for plumbing (or wire or any of its uses).

However, different forces apply, the causal mechanism is different, and the result is different.

In the case of a commodity, the manufacturer buys for the purpose of selling it in a different market. The profit = selling price – (purchase price + other costs). The manufacturer has a choice to buy copper or not buy copper. If the selling price of pipe is less than the buy price of copper, the manufacturer is better off not buying copper.

In the case of a bond, there is always a profit (assuming interest rates are positive). There may be a debate over whether the profit is sufficient to compensate the bond buyer for the loss of the currency. However, that debate goes away when we realize that the loss of the currency also occurs if the investor does not buy the bond. That is, if he just holds cash, he suffers the same loss.

This means there is not the same kind of choice, as in copper. In copper the choice is: do the trade or not. In bonds, the choice is: do this trade or … or what?

We noted one challenge faced by any would-be bond buyer who balks at the price being too high: non-bond owners suffer the same declines in the value of the currency as bond owners do. That is, the loss of currency value is invariant, applying to both alternatives. And is therefore not a consideration in the decision.

All Roads Lead to the Bond

Another challenge is that there is no way to hold a money[2] balance, without financing the government bond. In fact, there are four ways to hold dollars: (1) paper dollar bills, (2) a bank balance, (3) reserves held at the Federal Reserve, or (4) short-dated Treasury bonds (often called “bills”—throughout this article, when we say Treasurys we refer to the short-dated bills). Let’s look at each.

If you have $100, you can hold it via paper notes in your pocket. But bank notes are the liability of the Fed. The Fed issues its liabilities, to fund its portfolio of assets. Which is mostly Treasury bonds. To hold paper bank notes, therefore, is to fund Treasury bonds! You own Treasurys, indirectly, through the Fed.

Owning paper notes becomes impractical (not to mention risky) for larger amounts. If you have $100,000, you can’t hold it in your pocket, but you can deposit it in a bank. Now, your dollar balance is not a liability of the Fed. It is a liability of the bank, which the bank uses to fund its portfolio of assets. Which includes a large component of Treasury bonds. You have not avoided buying Treasury bonds, you have simple obscured it behind a bank’s balance sheet.

If you are a bank, yourself, then you don’t want to hold balances at other banks. However, you have an option not available to the little people: you can hold a balance at the Fed. As with the little guy who has five twenty-dollar bills in his pocket, the bank is funding the Fed’s portfolio of Treasury bonds. The Fed gets trillions of dollars this way, and it owns trillions worth of Treasurys.

Finally, you can own Treasurys directly. Even small, retail investors can buy short-dated Treasurys in a brokerage account. We include this in the list of ways to hold a money balance, because Treasurys are the root of the dollar system (see the description of Fed issuance of dollars, above). Treasurys are guaranteed by the government to return dollars invested at par plus interest. Short-dated Treasurys have little price risk, even when the interest rate moves.

There is no way to protest too-high Treasury prices (i.e. too-low interest rates). You have no way to avoid buying Treasurys, or at least funding a bank or the Fed to buy them. Unlike the preference of the pipe manufacturer, the preference of the investor has no teeth.

The Death of the Bond Vigilante

This is the logical consequence of a regime of irredeemable currency. Everyone is forced to be a creditor, and those who need to hold a money balance must be a creditor to the government. Whether they would or not. The people are disenfranchised. There is no such thing as a “bond vigilante”. The preferences of the savers have no teeth. We have been stripped of our choice by President Roosevelt’s fateful policy in 1933.

The savers do not set a floor under the interest rate, as they would in a free market. Indeed, there is no floor. Look at years of negative interest rates on Swiss, German, UK, and Japanese government bonds.

The savers are utterly impotent to move interest rates up, no matter their preferences and no matter how fast consumer prices are rising.

Rates can rise, and sometimes do. And we will discuss the process below. But first, we want to address other investments.

Obviously, if you don’t like the interest rate on Treasurys, you can buy other assets (we are certainly in favor of everyone buying some gold). However, these other assets are not a money balance. They are, well, other assets. And they come with price risk. If you trade $1,000 dollars for an asset, and later must sell it, you may get only $500.

It is not so simple to advise people to buy other assets, as a solution to the problem of too-low yields on Treasurys. The risk of capital losses is a powerful disincentive for many investors.

And anyway, it has no effect on the interest rate on Treasurys. This is because the seller of the asset gets the dollars paid by the buyer. He finds he is restricted to the same few choices that the buyer had. He can buy another asset, but that just puts the seller of that asset in the same trap. And so on.

There can be some gyrations, if lots of people sell Treasurys, as the cash ends up in banks, and the banks end up buying the same Treasurys in the market. But no durable fall in Treasury prices.

FDR is starting to look like an (evil) genius.

Interest rates shot up from just after WII until 1981. Much of that was during the last vestiges of the broken gold standard. But after 1971, we had the same irredeemable currency as now.

Some prominent voices in the gold community now say that we are again facing the same economic circumstances. Is this true? Will the force that drove the Fed Funds Rate from under 1% to 19%, cause a similar moon shot any time soon?

No.

Interest rates do not go up because savers want them to. Or because doom prognosticators fear they will. Or because the Fed promises to make them do.

Interest rates can rise only if there is rising demand for credit—i.e. increasing issuance of new bonds (plus some other conditions described by Keith in his theory of interest and prices). For rates to keep rising, there must be increasing new issuance despite—or because—of rising interest rates. That is, someone wants to borrow more, the more the cost of borrowing goes up.

(yes this is perverse)

The 1970’s vs Today

Back in the 1970’s, consumers were hoarding consumer goods such as canned food and paper towels. Corporations got in on the act, hoarding raw materials and even partially-completed work-in-progress. The difference between corporations and consumers is that corporations borrow—i.e. issue bonds—to finance their inventory hoards.

The more they did this, the more that both prices and interest rates went up.

In other words, it cost more to do it again, but the profits from the previous round increased, and hence the profit on offer to do it again is increased.

As rates go up, it affects corporations similar to the rising price of copper. A pipe maker cannot buy copper at $5.00, to sell pipe for $4.50. For the same reason, a corporation cannot borrow at 10% to earn an 8% return on capital.

The more the rate rose in the 1970’s (or any time), the more productive corporations normally cease to be borrowers. They cannot profitably borrow at the higher rates. So the game increasingly shifts to borrowing to finance inventory. The profit is not really coming from producing, but from inflation. Which squeezes out producers who had been borrowing to finance production. Which means less production. Which means reduced supply. Which means higher consumer prices. Which means greater profits to companies that borrowed to finance growing inventory hoards.

Smaug the dragon: 1. Dwarves of Erebor (toymakers): 0.

Do the conditions exist to enable this, today?

Corporations work for much lower returns than back in those days. And they are already loaded up with great debt burdens. Many are “zombies”—their gross profit < interest expense. We have linked before to the Bank for International Settlements paper, showing zombies reaching around 16% by 2018 (and rising, even pre-lockdown). This recent article claims 10% of US public companies are zombies, which is remarkable because public companies generally have options that their smaller, private competitors do not.

Is it true that lockdown, and subsequent whiplash, has caused supply chain and logistics snarls that persist even today 2 ½ years after the onset of Covid. Is it true that various other bad government policies, especially trade war and tariffs, have exacerbated this problem? Is it true that corporations have been forced to order in bigger batches, in order to remain operating? Yes, to all of these.

An Insatiable Appetite for Lowering Rates

But do they have appetite to keep on borrowing more, the more that they drive up interest and prices?

We phrase the question this way, throughout this part of the discussion, to emphasize that there is a dynamic involving interest, prices, and return on capital. It is impossible to grasp in terms of simple, linear, static quantities, such as comparing quantity of money to supply of goods. Or even change in quantity of money to supply of goods.

One has to think of the rate of change of appetite for something increasing as the cost of satiating that appetite increases. This is counterintuitive. And, as noted above, quite perverse. Yet it is inherent in the regime of irredeemable currency.

The answer is: no. No, they don’t have appetite (or capacity). There will not be endless waves of increased demand for borrowing, regardless of interest rates, to finance endless waves of hoarding of raw materials.

The demand for credit remains weak, except on a downtick of rates.

If this ever changes, then watch out for rates.

© Monetary Metals 2022

[1] The bond price and interest rate are a strict mathematical inverse. Like a seesaw, if the price goes up then that means the interest rate goes down. Thus we can say a bond price is above breakeven, to describe when the interest rate is below a threshold (e.g. the rate of CPI increases).

[2] Here, we use the mainstream notion of money