In economics, a “soft landing” widely refers to a moderate economic slowdown following a period of growth that manages to avoid a recession. Metaphorically it is similar to how the term is originally used in aviation — as in a pilot attempting to land an airplane smoothly without crashing.

When tasked with stopping an economy from overheating with high inflation, central banks like the US Federal Reserve typically aim to raise interest rates just enough to engineer such a slowdown (i.e. soft landing), but not enough for a severe downturn (known as “hard landing”).

While the quantifying factors to define a “soft landing” have long been debated, returning the inflation rate back or close to the 2% target without a deep surge in unemployment (preferably below 5%) is often seen as a base requirement.

The term “soft landing” first gained currency during the tenure of former Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan, who was widely credited with engineering one in 1994-1995. Current chair Jerome Powell has also suggested that the Fed achieved soft landings in both 1965 and 1984, and was on course for another one in 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic intervened.

The most impressive soft landing yet could well be the one Powell is about to pull off in combating what was the highest US inflation on record since 1981.

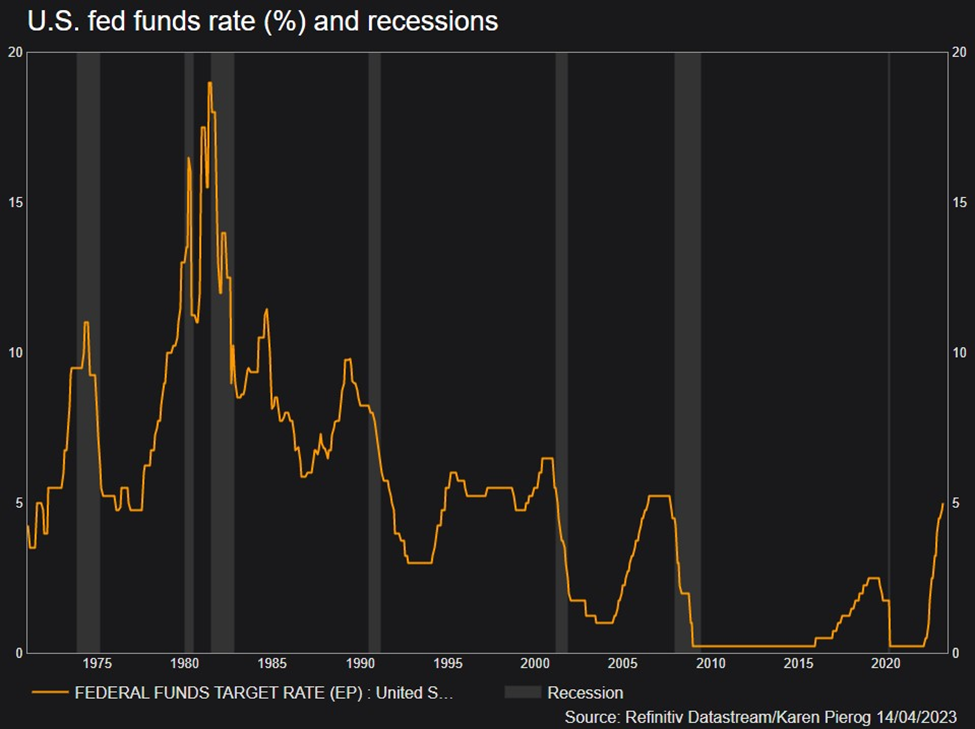

When the Fed began a series of interest rate hikes last March to kick off the current monetary tightening cycle, which, as things stand, has produced 500 basis points of rate increases, many feared that come this year, the economy could easily plunge into a recession, or at least come close to it.

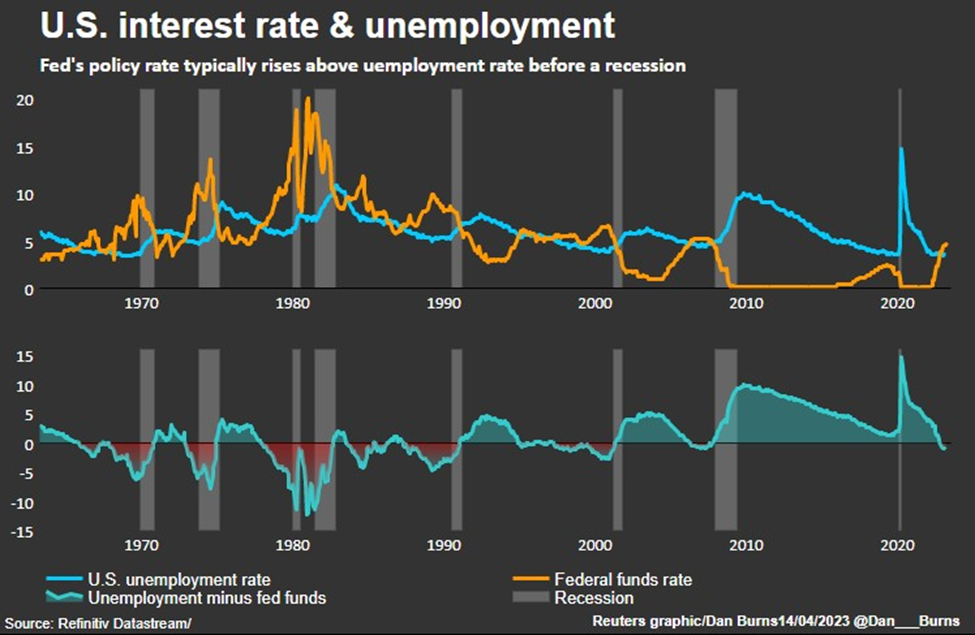

This is because aggressive interest rate hikes tend to make mortgages, auto loans, credit card borrowing, as well as business lending more and more expensive, which in turn takes a toll on the overall economy. It’s no wonder that most recessions in the US since the Great Depression have followed interest rate hikes by the Fed.

Amid the Fed’s most aggressive rate hike campaign in 40 years, it seemed like a soft landing was nearly impossible, well, at least around this time last year. In June 2022, headline inflation was 9.1%, and the thinking was the only way that was going to come down was if the unemployment rate (3.6%) shot up.

But after more than a year of rate hikes, inflation has come down to 4% and unemployment is at 3.7% — which is nearly the same. Not only that, but the US gross domestic product is still growing.

As a result, the notion that the Fed is on its way to engineering another “soft landing” has begun to gain more traction among economists and financial markets, despite months and months of recession talks.

But the question is, will it actually happen?

Soft Landing: How Hard Is It?

Conventional wisdom suggests that a Fed soft landing is quite a rare phenomenon.

Strictly speaking, the US central bank only accomplished that feat once in the last 60 years. As mentioned, this occurred in the mid-1990s under the guidance of Alan Greenspan, after the Fed doubled interest rates to 6% between February 1994 and February 1995.

A hard landing though, is much more common under such circumstances. A recession followed the last five instances when inflation peaked above 5% — in 1970, 1974, 1980, 1990 and 2008.

So to expect a soft landing following the current tightening cycle (with interest rate already gone above 5%) would be like hoping for a miracle. That is, if we’re only basing it on the textbook definition.

A more flexible perspective makes a soft landing a much more common achievement than generally believed.

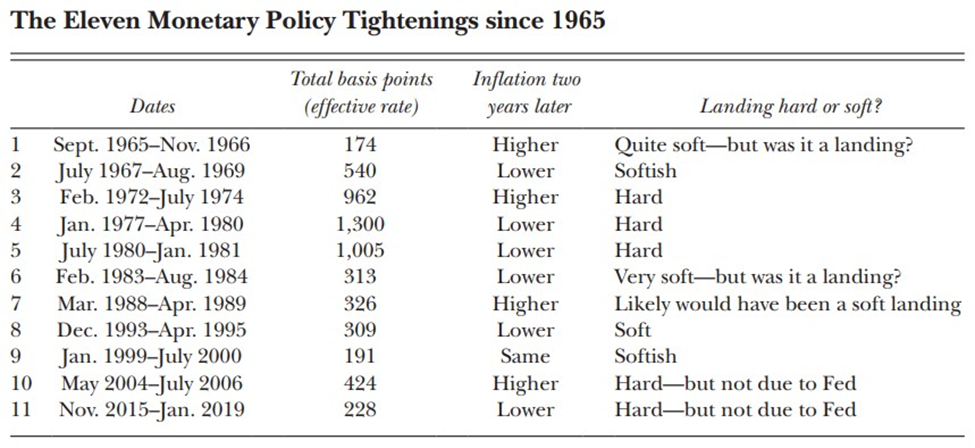

In a paper published earlier this year, former Fed Vice Chair Alan Blinder — who was in situ during that fabled 1994-95 soft landing — says that the US central bank actually has a better record than that — as long as the criteria for softness are not too stringent.

According to Blinder, it is “difficult, maybe impossible” to predict the timing of monetary policy changes on the real economy. What Milton Friedman previously called the “long and variable lags” between policy decisions and their effects on the economy can be anywhere from six months to two years. And a lot of it is really down to luck, given the external factors that are out of the Fed’s control.

Blinder posits that the soft landing parameters of avoiding recession completely are too narrow. He argues that if GDP declines by less than 1% or there is no recession determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research for at least a year after a Fed tightening cycle, that is a “softish” landing.

By this looser definition, Blinder reckons that five of the 11 Fed tightening cycles since 1965 were followed by soft landings to varying degrees, and the 1990-91 recession was due to Saddam Hussein and Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, not Greenspan’s policies.

So gives the Fed a near 50% success rate — much better right?

And of the five hard landings, two were not a result of Fed monetary policy: the Great Recession of 2008-09 was because the financial system imploded, and the 2020 recession was a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

That just leaves us with three recessions (1973-75, 1980 and 1981-82) that can fairly be considered hard landings and a direct result of high interest rates. It’s no coincidence that they followed what were by far the three most aggressive tightening cycles (see below).

Source: Reuters

Source: Reuters

As Blinder says, the landing largely depends on how high the ‘plane’ is flying before it starts its descent. To extend the analogy further, Powell and his colleagues are flying blind now, given the fog created by post-COVID pandemic supply chain disruptions, and food and energy shocks.

To achieve another soft landing under these circumstances, the Fed will have to be skillful, as well as not encounter any adverse external shocks, Blinder concludes.

2023: A Case of Success?

Even with a more lenient view on what a “soft landing” should be, the Fed’s record is mixed because it doesn’t exercise nearly the same control over the course of the economy as a pilot has over the aircraft.

The Fed’s main policy tools — interest rates and asset holdings — are simply blunt instruments not designed to account for supply chain disruptions or health crises. So, skill and luck play an important role — and also timing.

As things stand, the Fed — under the stewardship of Powell — may have a chance to steer the economy towards another soft landing, especially if we use the stretched definition: a mild technical recession while keeping jobless rates below 5% under “full employment” assumptions.

A paper published last year by the Bank for International Settlements using even looser definitions for hard and soft landings than that used by Blinder confirms that the Fed indeed has a fighting chance.

The paper analyzes 70 tightening cycles between 1980 and 2019 across 19 advanced and six emerging economies.

According to BIS, a hard landing is a recession characterized by two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth within three years of the interest rate peak; otherwise, it is a soft landing.

The tightening cycles were defined as at least three consecutive quarters, ending with the policy rate at its peak.

Of these 70 episodes, 41 ended with a hard landing and 29 with a soft landing. All else equal, larger rate hikes spread over a longer period are more likely to be associated with hard landings, and front-loaded tightening cycles tend to be followed more frequently by soft landings, the BIS found.

The Fed’s latest cycle falls under the second category.

Paul McCulley, adjunct professor at Georgetown University and former chief economist at bond giant Pimco, believes the Fed is at the end of its cycle even though inflation remains well above the central bank’s 2% target.

In a Reuters report, he draws parallels with the end of the 1994-95 hiking cycle, particularly Greenspan’s remarks in February 1995 that the US central bank could keep rates on hold or even cut them “despite adverse price data”, if there were signs that underlying inflation pressures were cooling.

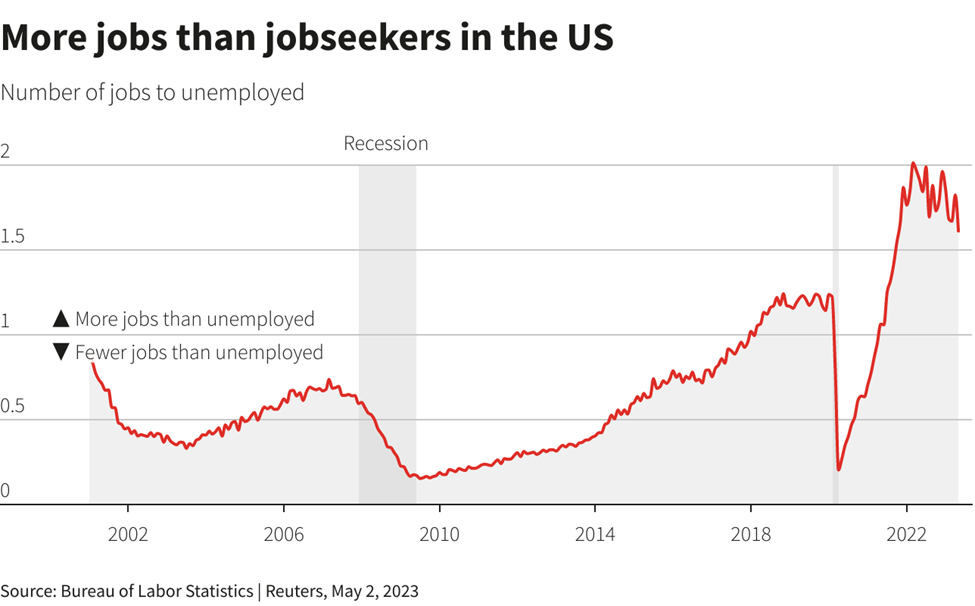

Judged by the remarkable strength of the jobs market this time around, even as inflation slows and the historically brutal Fed hiking campaign nears an end, it’s not hard to see why hopes are rekindled, Reuters columnist Mike Dolan recently wrote, adding that the ebbing of regional US banking crisis also helps.

During the month of May, the US labor market remained resilient despite another round of Fed rate hike (the 10th of the current cycle), adding a total of 339,000 jobs and taking the unemployment rate to just 3.7%.

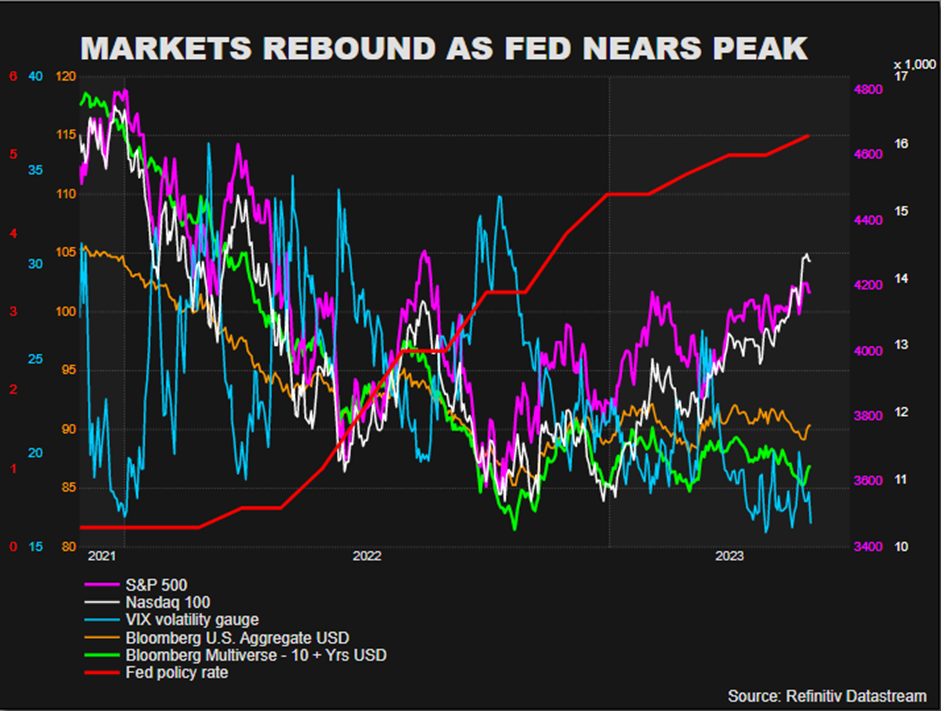

Still, as Dolan reminds us, whether a “soft landing” is possible really depends on whose perspective you take. A gentle bump on the tarmac for most households may not feel that “soft” for investors, who have arguably already suffered a hard landing in one of the worst annual recoils in both stocks and bonds on record last year, he noted.

Fed Growing Hopeful

On the Fed side, the view has certainly been more upbeat than what it was at the end of 2022.

In new economic projections last month, Fed officials appeared to confirm a “soft landing” outlook by raising their median 2023 growth projection to 1.0%, which is more than double the previous forecast of 0.4%. This essentially revises their implicit recession call in the process, and importantly, changes their mind about whether a soft landing is realistic.

Bear in mind that the US economy expanded 1.3% in the first quarter and is on course to grow around 2% in the second, according to the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow tracker. This would point to slight growth in the second half of the year.

They also lowered their 2023 unemployment rate forecast and trimmed the outlook for the next two years, while slightly raising their 2023 inflation outlook but keeping their 2024 view unchanged.

Previously, Fed officials were predicting that unemployment would rise to 4.6% from 3.5%. In the eyes of some economists, a rise in the unemployment rate of more than 1% was seen as the Fed essentially trying to engineer a recession to bring down inflation.

The same officials are now predicting that the unemployment rate will rise to only 4.1% (from the current 3.7%) by the end of the year, and 4.5% for the next two years.

Meanwhile, the median projection for overall inflation (as measured by the personal consumption expenditure index) has fallen to 3.2% from the 4.4% set in April of this year, mirroring the Fed’s optimism in bringing price levels down.

The Fed is expected to raise interest rates by another 50 basis points some time in the future. Currently, its benchmark interest rate is around 5%, after beginning the tightening at near zero in March 2022. Fed officials are projecting that this rate will be 5.6% by the end of 2023.

“We have been seeing the effects of our policy tightening on demand in the most interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy, especially housing and investment,” chair Powell said in a press conference on June 14.

“It will take time, however, for the full effects of monetary restraint to be realized, especially on inflation.”

Markets Upbeat

Improved market sentiment is also making the rounds within the financial sector, based purely on the economic indicators seen during the first half of 2023.

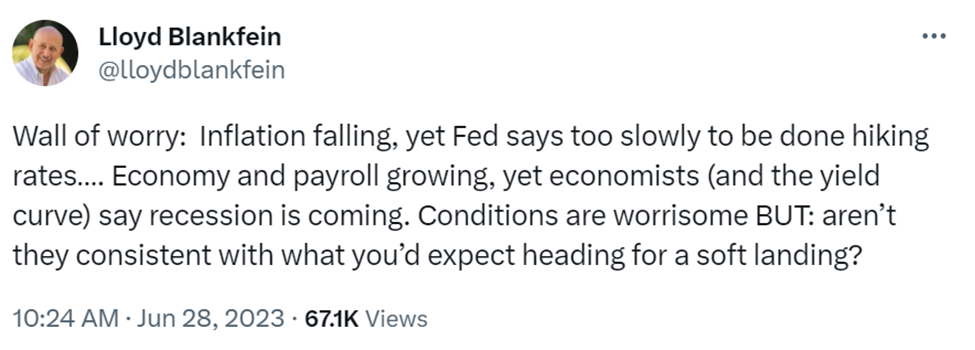

The latest batch of economic data has opened the door to the US economy possibly avoiding a recession, according to Lloyd Blankfein, the former chief executive officer of Goldman Sachs.

Blankfein also took issue with arguments that the US was heading for a hard landing, saying that “the growth of the US economy combined with rising payrolls disputes high recessionary odds displayed by the bond market and other economists.”

“Conditions are worrisome BUT: aren’t they consistent with what you’d expect heading for a soft landing?” Blankfein wrote in a June 30 tweet.

“The economy is more resilient than the market realizes,” BlackRock’s chief executive Larry Fink said recently, adding more interest rate rises will be necessary but that he saw no “evidence that we’re going to have a hard landing.”

Chamath Palihapitiya, founder of venture capital firm Social Capital, also sees the Fed successfully achieving a “soft landing”, predicting that economic growth will slow but not “crater”, with the US central bank likely close to the end of its tightening cycle after it “skipped” a rate hike earlier this month.

Speaking to Business Insider, the so-called “SPAC King” also mentioned that renewed optimism about the economy will then give way to “a sustained forward-looking rally” in the stock market and a 2024 where rates can slowly be cut.

Those at Morgan Stanley are much more sanguine in their economic outlook, predicting that the US will “dodge a much-predicted recession” thanks to a resilient labor market that has endured the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes.

In an interview with Yahoo Finance last week, the bank’s global chief economist Seth Carpenter said he’s anticipating that the central bank will be able to achieve its dream scenario of a “soft landing” – where it brings inflation down to its 2% target without wiping out huge numbers of jobs.

In Carpenter’s view, the labor market has been one of the key stories so far this year. “There has been clear slowing, however, the rate of job gains has been pretty strong and we think that’s been contributing to resilience spending,” he stated.

Carpenter went on to say that while he does think the US economy is slowing, recent jobs data shows it still is in a “pretty solid place for now”.

“We are seeing job openings come down, but we’re not seeing a lot of firings,” he explained. “I think that’s reflective of the fact that you can get a slowdown in the economy and easing of pressures without there having to be really an outright contraction or a hard recession.”

Too Soon to Applaud?

Still, it might be too soon to draw any sort of conclusions on a potential “soft landing”.

“After recent Goldilocks economic reports, maybe we don’t get either a hard landing or soft landing. Maybe we get NO landing,” Blankfein said in a follow-up Tweet to its previous one. The “no landing” scenario, as Reuters’ Dolan describes, is exactly where the markets stood prior to the banking stress of March 2023.

Many prefer to take the “wait and see” approach before giving the Fed its flowers. Among those is Ann Owen, who formerly worked at the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and is now an economist at New York-based Hamilton College.

“Jay Powell might deserve a standing ovation if he actually does land this economy softly. It would be only the second time in history the Fed has significantly raised rates and tamed inflation without causing a recession. But any applause would be premature right now,” Owen said in an interview with Marketplace.

“The captain has rung the little bell, told the flight attendants to go through the aisles and pick up the remaining garbage — but we haven’t landed yet,” she said using an analogy with passenger planes.

Keep in mind, a successful landing needs everything the pilot can control to fall into place, but external forces can always emerge.

“In March, we had three regional-level banks fail,” Julie Smith, an economist at Lafayette College, said in the same interview. “I think the foreseeable shock is still going to end up being in the banking sector.”

Not to mention those unknown unknowns that can wreak havoc with the “flight controls” — like Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Ironically, consumers feeling better about the economy now could fuel further inflation. “If consumers believe we’re out of the woods — particularly with the lifting of the debt ceiling in combination with easing inflation — they may feel more comfortable spending in the months ahead,” noted Joanne Hsu, who runs the Consumer Sentiment Survey for the University of Michigan.

The Morgan Stanley Global Investment Committee agrees that there are reasons to be cautious. “While we are far from calling a US recession, we do think there are two substantial risks investors should keep in mind as they weigh portfolio positioning for the months ahead,” the committee says.

The first is that rate hikes alone may not be enough to tame inflation. Borrowing has not been a major driver of inflation during the current economic cycle, so hiking rates—and making it more expensive to borrow—may have limited effect, says Lisa Shalett, Morgan Stanley’s chief investment officer, wealth management.

Over the past 12 years of near-zero rates, borrowing costs have stayed incredibly low, and inflation, until only recently, had been relatively muted, she noted.

According to Shalett, the ample cash balances among businesses and households appear to be what’s driving much of today’s inflation-fueling excess demand. “What’s more, many of the recent supply chain problems behind today’s inflation have nothing to do with the Fed’s baseline rates; they stem from effects of COVID, deglobalization, demographic change and geopolitical-related commodity price surges.”

As such, she believes a mix of policy action is needed to combat inflation—not just rate hikes, but a reduction of the Fed’s nearly $9 trillion balance sheet as well. Morgan Stanley’s economics team expects the Fed to run off about $500 billion through year-end.

“Despite this, there is still significant uncertainty about how much liquidity withdrawal the market and economy can tolerate before becoming destabilized,” Shalett writes.

Most asset managers echo the same concerns, as the combined effect of monetary tightening and ongoing liquidity withdrawal in the US – alongside more restrictive fiscal policies – continues to make many investment houses fret.

“Nothing easy or pleasant is usually associated with episodes of liquidity withdrawal as intense as the one that the global economy is now experiencing,” State Street Global Advisors’ chief economist Simona Mocuta told clients.

The second risk factor is that the global consumer spending outlook remains uncertain. Shalett says spending is still heavily skewed toward goods, and as demand normalizes back toward services, demand for goods could weaken just as supply chain bottlenecks are clearing and inventories are rebuilt.

“Trying to gauge how this shift might unfold is particularly challenging today, with consumers sending conflicting signals,” she notes. “Add to all this the likelihood of weakening international demand due to geopolitical instabilities, and we have a rather muddy outlook, with possibly greater risks to the Fed’s efforts.”

Conclusion

At the end of the day, there’s no exact rulebook on what can be labelled a successful “soft landing”. If we’re strictly using the standard criteria — i.e. reaching a 2% inflation target without triggering a recession — then the Fed still has some work to do.

The latest economic data showed US consumer spending has essentially stalled since a surge in January, which may help ease price pressures but could also set up the economy for a sharp slowdown.

On the other hand, the key inflation gauge did drop below 4% for the first time since early 2021. This is right after Fed Chair Jerome Powell suggested at the end of June that two more rate hikes are likely necessary this year to bring inflation down.

It’s the latest inflation readings and job market data that are buoying the optimism of at least a “softish” landing, as Blinder’s paper suggested — the one “silver lining” in the Fed’s outlook if you will.

“Reaching 2% – or close enough that the difference will not matter – in 2024 is not such an impossible hurdle as the general opinion seems to imply,” State Street’s Mocuta said.

However, much would boil down to just how severe a US recession is, should it arrive, given that Fed’s policy rates tend to rise above unemployment rates before we reach that stage.

“Restraining demand is just a euphemism for creating a recession and raising unemployment,” said Phil Suttle, founder of consultancy Suttle Economics. “We will have a recession, the only question is how severe.”

Does a mild recession count? Some are willing to give the Fed a bit of leeway, while others prefer to be extra cautious in light of the pernicious risks (i.e. geopolitics, energy volatility, the lagged effect of credit tightening on real estate).

In a recent interview with Kitco News, Axel Merk, president and chief investment officer at Merk Investments, says he is not convinced that the US central bank will be able to get inflation under control before it breaks something in the economy or financial markets.

Looking at the inflation threat, he adds that “with so much debt in the system, there is very little political will to bring inflation down.”

But as Reuters’ Mike Dolan says at the end of his column, the prospect of sustaining the targeted inflation rate at least turns off the seatbelt sign, only for now.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.