The giant federal debt we’ve been talking about isn’t just borrowed money. It is also lent money. Loans are two-party transactions. One side receives temporary use of cash which it agrees to repay with interest. The other gives up the current use of that cash in exchange for receiving interest. Ideally, it works out for both… but not always.

The key challenge is finding an agreeable interest rate. Borrowers can only afford so much. The lender needs a rate high enough to compensate for its risks, which include the possibility of not being repaid (i.e., credit risk) and external events like inflation. This necessarily involves assumptions about the future, which may prove wrong.

When a national government borrows money, other factors enter the equation. Repayment risk may be lower because governments have taxing powers, but governments also control and/or influence the currency, the central bank, commercial bank regulations, the court system, and more. Political borrowers have a lot of power over their lenders, if they choose to use it. The lenders’ main power is limited to refusing future loans, or at least demanding higher interest rates.

I’ve talked a lot about the borrower’s side of the debt situation. Today we will look at the lenders. Who is lending all this money to our spendthrift government, and why? What’s in it for them? Might they decide to stop?

Borrow at Will

The US Treasury Department doesn’t have to visit a banker, hat in hand, when it wants to borrow money. The opposite is more accurate. Treasury holds periodic auctions to which it invites the bankers, giving them the “opportunity” to have Uncle Sam borrow their money. (Note the power imbalance.)

Let’s also make sure the terminology is clear. “Buying a bond” is the same as “lending money.” It may sound more sophisticated, but that’s just language. At Treasury auctions, lenders hand over cash in exchange for a promised future repayment. That promise can be resold in the bond market. Some purchasers hold bonds to maturity, some actively trade them. But all of it sits as an asset on someone’s balance sheet, neatly matching the liability side of the Treasury’s balance sheet.

Who are these lenders/bondholders? The Treasury Department keeps track of this (it’s always good to know your lenders). The calculations below come from Wolf Richter of the Wolf Street blog, who nicely summarized the current situation last week.

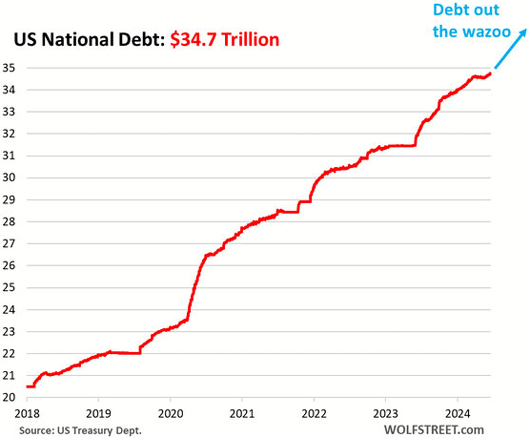

Start with the total: Latest data shows total federal debt at $34.7 trillion. (Debt out the wazoo is a technical market term.)

Source: Wolf Street

Of this $34.7 trillion, some $7.1 trillion is held by the Social Security Trust Fund and various governmental pension plans. These bonds are never traded; the funds buy them directly from the Treasury and hold them to maturity. They have no market impact but still count as “debt.”

That leaves $27.6 trillion in “debt held by the public.” Some of these are in non-traded savings bonds; the remaining $26.9 trillion are the Treasury bills, notes, bonds, Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) and Floating Rate Notes which together comprise the “Treasury market.” We call them “securities” because they can be bought and sold, just like stocks or corporate bonds.

Of this $26.9 trillion in Treasury securities, foreign holders owned $8 trillion (29.7%) at the end of Q1. This includes foreign governments, central banks, and private investors. We will look at the country breakdown below. American investors and institutions owned the remaining $18.9 trillion, as follows:

- Mutual funds: $4.8T

- Federal Reserve: $4.6T

- Individuals: $2.6T

- Banks: $2.2T

- State and local governments: $1.7T

- Pension funds: $1.2T

- Insurance companies: $510B

- Other: $400B

Again, this was as of the end of Q1. It has already changed but the broad outlines should still be similar.

Let’s talk about those foreign lenders. I’m often asked what will happen when/if the Chinese or others decide to stop buying our Treasury securities. This leads to a bunch of other questions. How dependent are we on foreign lenders, who are they, what are their motivations, and could/would they ever make that kind of move? And if so, what would be the result?

As noted above, foreigners presently own just under 30% of the outstanding marketable Treasury debt—roughly $8 trillion. A large sum, obviously, but these aren’t necessarily foreign investors. Much of it is held as central bank reserves. Another large part is used to facilitate international trade, since importers and exporters recognize our Treasury debt as more liquid and stable than alternatives.

The global banking system is set up such that most cross-border transactions ultimately settle in US dollars. Could that change? Sure. The Chinese are working toward it. But for now, the dollar is critical to world trade, which means a lot of non-discretionary demand for reliable, liquid dollar-denominated assets. When Americans buy stuff from abroad, foreign exporters have to take our dollars, which as a practical matter means they buy our Treasury debt. They need it the same way your car needs grease. It keeps the wheels turning.

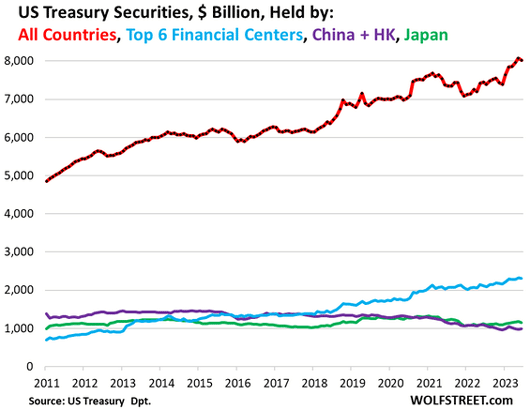

That said, the distribution of foreign Treasury demand can change, and it has been. Here’s another informative Wolf Richter chart.

Source: Wolf Street

The red line at the top shows total foreign Treasury holdings growing steadily since 2011. The lighter blue line shows the portion held in the six largest non-US financial centers: the UK, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, the Cayman Islands, and Ireland. The purple line is China (including Hong Kong) and the green line is Japan. The scale makes those changes hard to discern, but in percentage terms they’re significant.

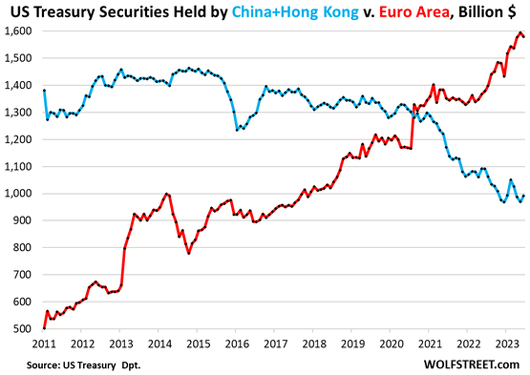

This next chart zooms in to tell us more.

Source: Wolf Street

The red line is the Euro area, which partially overlaps the first chart’s Top 6 financial centers category. We see that region’s US Treasury holdings rose considerably since 2020 while China’s dropped. This is partly a result of COVID snags that reduced US imports from China, and also US policy to discourage certain kinds of trade for national security reasons.

This could revert back but, if you’re concerned about our lenders going on strike, the Europeans should be a bigger worry than the Chinese. Canada, Taiwan, and India are also becoming heavy Treasury buyers.

While foreigners are buying more Treasury securities, our debt has grown even faster. This means something perhaps counterintuitive but critical.

- The amount of US debt held by foreigners has been growing, while

- The percentage of US debt held by foreigners has been shrinking.

Now consider where US policy is going. We are trying to become more resilient and less dependent on imports due to both the COVID era’s disruptions and security concerns vs. China. More tariffs and other protectionist policies are likely no matter who wins in November. While Biden (rightly, in my opinion) criticizes the Trump tariffs, note that he did not end them. Meanwhile, the debt is certain to keep growing.

This suggests foreign Treasury demand could start falling not just relatively but in absolute terms as well. Yest as the debt grows, Treasury will need more buyers. How to attract them?

The likely answer: higher yields. Which will of course make the deficit worse. Just ugh.

Interesting Times

Treasury bondholders are the US government’s lenders. They are being paid interest to finance that part of the federal government’s activities which tax revenue is insufficient to support. How well are they being paid?

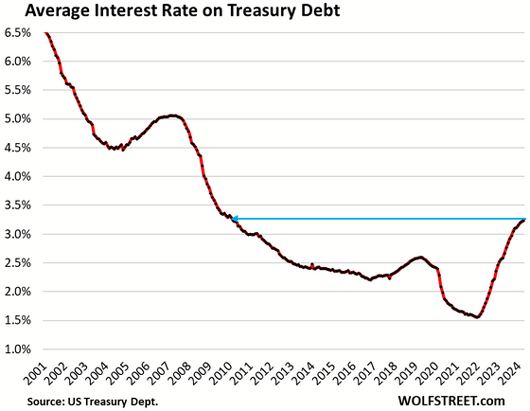

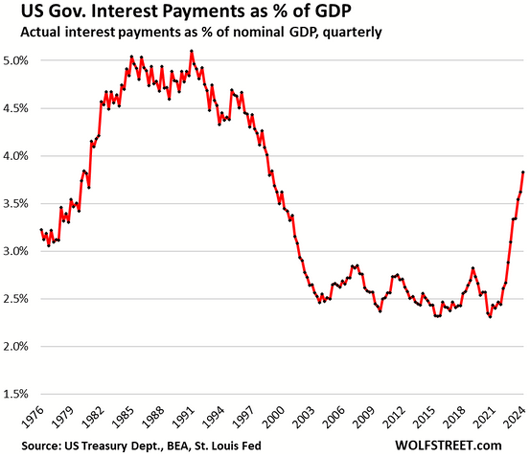

Here we need to make a distinction. Most Treasury debt (except TIPS and FRNs) is issued at fixed rates. This defines the government’s interest cost. But once issued, the yield of a Treasury security will change based on its market price. This doesn’t affect the Treasury’s interest bill. The Treasury yields you see quoted in the news aren’t what the government actually pays. That rate looks more like this:

Source: Wolf Street

The Treasury regularly auctions new debt at various maturities. It also redeems maturing debt, so the mix is constantly changing. The average rate shown in the chart is a blended number which, as you can see, rose quite a bit since 2022 and is now at the highest point since 2010. It will likely keep rising as debt issued between 2010 and 2022 rolls off and is replaced at higher rates.

Treasury holders take these deals because they believe their yields fairly compensate for the time value of their money as well as inflation and other risks. But the chart suggests this willingness is diminishing. Treasury investors think risks have increased enough to demand a bigger piece of the pie.

Source: Wolf Street

Federal interest, expressed as a percentage of GDP, spent almost 20 years in a range around 2.5% of GDP. That means both GDP and debt were growing at about the same rate. As a lender, you can live with that. Your borrower’s debt load is sustainable, though perhaps unwise.

This has now changed as federal interest costs approach 4% of GDP. That means financing costs are now growing faster than the economy, which is also the tax base the federal government can tax. Would commercial lenders be so accommodating to a household or business like this? Probably not.

Yet we have to recognize how markets work. Risk has a price. However crazy the deal you’re selling may be, people will buy into it if you pay them enough. Everyone is creditworthy at the right interest rate. Seriously, Argentina was able to sell debt even after repeated national defaults.

The US advantage of owning the world’s reserve currency has served to subsidize our debt. Dollar demand from the rest of the world has kept our interest rates lower than they would otherwise be. I am not saying this will change soon, but I think it will change. And as it does, even if ever so slowly, our debt challenges will grow.

The problem won’t be that the Treasury faces a buyers’ strike. The problem will be the higher and higher rates needed to attract buyers. Who, if trade policy evolves as I expect, will have to be increasingly domestic.

We know where this is going, but getting there will take time. It may be a “frog in boiling water” kind of path. As the fiscal balance deteriorates, the auctions will gradually push yields higher, with the exception of a recession or a real global crisis. Some investors will see that extra quarter point or whatever and rush to grab it. Their eagerness will push rates back down. Then the process will be repeated at a slightly higher level. Eventually the water will boil.

When Eventually Finally Happens

I had a long conversation with my friend Lacy Hunt this week. He is still in the deflation camp, but generally because he believes the Federal Reserve will hold the line on inflation. My question to him was if we were running $2 trillion and then $3 trillion deficits, pushing that money into the economy, how do we not have more inflation? The answer basically boiled down to the Federal Reserve will have to push back against inflation even if it means higher interest rates.

The growing national debt is a drag on GDP growth. Anybody who says it's not is not paying attention to the actual numbers. I don't think it's even up for debate now, unless you are Paul Krugman. When interest on the debt is growing faster than the economy, that is not sustainable, and means the bond market (lenders) will soon be asking for higher interest rates. With the deficits rising, and especially with a potential recession in our future at some point (I am no longer predicting when), the deficit will rise more.

Lacy says rates will eventually come down if the Fed continues on its inflation fighting path. But when Powell is replaced when his term is up in 2025, does anyone think that whoever is president will appoint an inflation hawk? It's going to get very awkward after that. Dropping rates too low will spur inflation and then we are back in the dilemma of 2021‒22.

Maintaining the higher interest rates necessary to hold inflation at bay will raise the US government’s borrowing costs and further enlarge the debt. We are past the point of any good choices.

This is a rock and a hard place. If the next Fed chair decides to cut rates while we have a $2‒3 trillion deficit, it could easily lead to much higher inflation. Throw in a recession? Choices get ugly. Louis Gave and many others thinks we are looking at an inflationary boom which could lead to higher rates! We could see a stagnant, slow-growth economy as debt rises, crowds out investment (which it is doing now—another letter) and very slow GDP—Japan or Europe or worse. Or maybe our government decides to cut spending and raise taxes and get the deficit crisis under control. AKA austerity.

We don’t know the future. I am repositioning my portfolio over time to buy large-cap dividend stocks and high-quality alternatives, with David Bahnsen managing the bulk of that portfolio. But that could change as we get further along and get a clearer picture of the nature of the crisis. Between David and I we can make course corrections. I wrote about what I was doing months ago, but reader questions tell me I will need to do so again.

Again, someone will buy the debt if the rate is high enough. That’s not good news because even at today’s relatively low rates (compared to pre-2010 in the chart above), simply financing past debt consumes more and more tax revenue. It’s about 35% now. At times in the 1980s it was near 50%. At the rate this is going, we could see that again within a few years.

We can’t rule out a disorderly crisis in which the Treasury market just breaks down. All this is based on trust: that the dollar will hold value, that the government will pay its bills, that the US economy keeps growing, that no world-changing “accidents” happen.

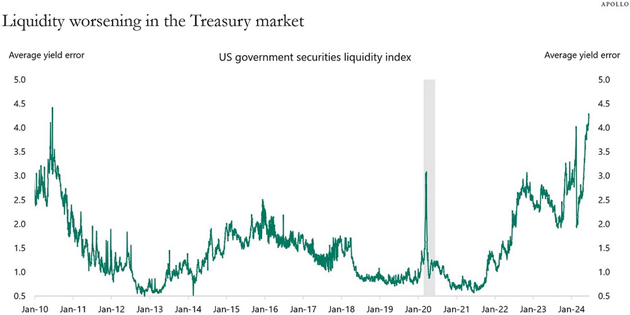

Trust is fickle. Trust (confidence) can break down quickly (as I noted in last week’s letter). We may already be seeing early signs of it. Torsten Sløk shared this chart last week.

Source: Apollo Global Management

The line tracks a Bloomberg index of Treasury market “yield errors,” i.e., when yields temporarily diverge from fair value. Think of it as chinks in the armor: not immediately dangerous, but a potential vulnerability if allowed to grow. These errors are becoming more frequent.

This doesn’t mean a crisis is imminent. It does suggest a crisis is coming.

I started this letter by noting that debt has two parties. In the US government’s case, we have no reason to think the borrower will be able to stop borrowing. Yet lenders have limits, too. They need confidence in being repaid on time, in a currency that is worth something.

For now, this giant borrower and its many lenders are able to reach terms. The terms will change. And when they do, the real crisis will begin.

Fishing and Killing Alligators

If you are not expert in how bonds work, our friend Jared Dillian has developed a Bond Masterclass that tells you everything you need to know about bonds of all types. You can get it here—it’s a great value.

The next planned trip I have is to British Columbia for a fishing trip at the West Coast Fishing Club with 30 of my friends and readers, kicking off a month-long celebration of my 75th birthday. I'm sure there will be some trips between now and then as always seems to happen.

In a conversation today with the host of the camp, somehow the story came up of what I do that could bring so many people to their camp. I flashed back on a story from 30 years ago. My daughter Melissa, who was at the time I think in the 2nd grade, came in while I was immersed in a book or a project and asked me what I did for a living. I flippantly told her that I killed alligators. Of course, I was alluding to the old joke about it's tough to remember that the original project was to drain the swamp when you're up to your derrière in alligators. (Microsoft would not let me dictate the word ***.)

Two days later I was at her school and her teacher asked me what I did for a living. I gave her an explanation and then she told me that she had assigned her students a project to ask what their dad did for a living and come back and tell the class. Melissa, evidently proud, told her class that I killed alligators for a living. Way cooler than being a doctor or a lawyer. OK, then I felt like a derrière.

I try to avoid politics in this letter. I have readers on both sides of the equation and my gig is economics and finance, not politics. I have been telling friends for weeks that I think the inside White House and Democrat establishment talked Biden into doing the earliest debate in history, suspecting what would happen. This was a political assassination. The whole thing seriously depressed me. I felt sorry for the man (I too am getting old – my father died of dementia at 88 – and notice I'm slowing down like dad did) and worried for our country.

But this I believe: The Republic will survive. Whoever wins in November, we'll have a rough four years and then a crisis. But we will get through it and life will be better. None of us will want to go back to the “good old days” of 2016‒2024.

With that, it's time to hit the send button and wish you a great week. And don't forget to follow me on X!

Your still up to his *** in alligators analyst,

|

|

John Mauldin |

P.S. If you like my letters, you’ll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price.

Click here to learn more.