When we think of global food insecurity, the United States is not top of mind. At least, it shouldn’t be. In fact, over 50 million American households out of a population of 328 million are food insecure — ie., lacking access to healthy food.

A study by Northwestern University found the pandemic has doubled food insecurity and tripled it among households with children, meaning one in six adults and one in four kids are not eating properly due to economic reasons.

Of course, hunger didn’t begin with the coronavirus, but it has made it worse. Feeding America estimates 35.2 million people faced hunger in 2019, compared to 54 million in 2020.

The current throng of unemployed workers, nearly 10 million who have lost their livelihoods owing to virus-related layoffs/ business closures, contributes to another problem — less people working means fewer contributions to the needy.

Certainly the plight of the poor, and working poor, has improved over the past few months in the United States. Trillions in covid-19 stimulus has been rolled out, including direct payments of $600, $1,200 and $1,400. Large swaths of the economy (more so than Canada) have opened up, a third of the population, or 107 million people, has been vaccinated, and unemployment has fallen to a less dire 6.1%.

US stock markets were knocked back this week but that might not be a bad thing. They are looking decidedly bubbly, as investors throw everything but the kitchen sink into equities, confident that a booming economy will keep stock valuations lofty and dividend payouts secure.

Source: Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo Finance

US Treasury yields, which for most of last year hovered near 0%, have been rising, as investors exit bonds and enter stocks, causing Treasury prices to fall and yields to rise. (The US Federal Reserve continues to buy bonds at a rate of around $120 billion per month, keeping yields from climbing very high)

Source: MarketWatch

Source: MarketWatch

Yet despite all of this good news, an elephant in the room threatens to stomp all over the tender green shoots of economic recovery, and that is inflation — or more specifically, food inflation.

Everything going up

North Americans have likely been noticing their trips to the grocery store are getting more expensive.

The pandemic has put tremendous pressure on supply chains, and the prices of many agricultural commodities such as grain, corn and soybeans, have skyrocketed. This is due to a number of reasons including heavy demand from China, the world’s largest consumer of commodities whose economy grew at a blistering 18% in the first quarter, bad weather and drought —dealt with separately in an upcoming section.

A shortage of supply, and a need to replenish hog herds after an outbreak of deadly African swine fever, is expected to push corn imports to 28 million tons this season, the most on record, according to Bloomberg data.

The news sent corn prices to over $6 a bushel, an 8-year high.

Over the past year, corn has nearly doubled (+84%), soybeans have gained 72%, sugar is up 59%, wheat has climbed 19% and coffee has risen 13%.

According to the World Bank, global food prices have gone up by 38% since January, 2020.

Increases in the prices of grains, like corn and soybeans used in animal feed, typically get passed down the supply chain to the prices of meats, including chicken, pork and beef.

A recent Troy Media column states many food manufacturers have already signaled that processing costs have gone up, making it practically certain that retailers will mark goods higher to protect their margins.

Canada’s Food Price Report predicts that prices will increase as much as 5% this year, representing almost $700 more for groceries, for the average Canadian family.

In the United States, food prices climbed 2.4% in April, compared to the same month a year ago, including a 3.8% rise in restaurant and take-out meals.

It isn’t only groceries that are increasing in price.

The Wall Street Journal reported on Wednesday that the US consumer price index (CPI) surged in April by 4.2%, the most in any 12-month period since 2008, as economic activity picked up but was constrained in some sectors by supply bottlenecks.

Among the costlier items, gasoline rose 50%, while the prices of used cars, representing a third of the CPI increase, climbed by 10%, the most on record; car and truck rentals shot up 82% and airline fares leapt 9.6%.

Gas prices were recently influenced by a cyberattack on the nation’s largest energy pipeline network. The May 7 attack on Colonial Pipeline prompted it to halt 2.5 million barrels a day, triggering fuel shortages panic buying and higher pump prices in the southeastern United States.

A video embedded into the WSJ story, narrated by a reporter, states that rising prices are being noticed in a wide range of consumer products, everything from produce, apples and berries, to meat, packaged foods, foil wrap, home appliances, and lawn & garden products.

As for what is causing this inflation, part of it is bad weather, such as the winter storm in Texas that interrupted the supply chain for resin, used in packaging.

Lumber, also used to package goods, has quadrupled due to skyrocketing demand for housing, fueled by rock-bottom interest rates, as well as a shortage of processed wood.

Some companies are running low on drivers and are having to pay them more, which is trickling down the supply chain to higher shipping costs.

Consumers are reacting to the price increases by choosing store brands over name-brand products, buying cheaper frozen food instead of fresh, enrolling in awards programs and driving less.

The reporter who looked into the issue thinks that prices will continue to rise both for food and household products — a view that appears to be shared by experts.

“The CPI data point feeds into a myopic narrative that the US is overheating and the Fed is one step away from tightening,” Bloomberg quoted Mike Bailey, director of research at FBB Capital Partners, a wealth management firm.

US stocks slumped this week after a report showed inflation rose more than forecast, stoking concerns that price pressures could stifle a recovery.

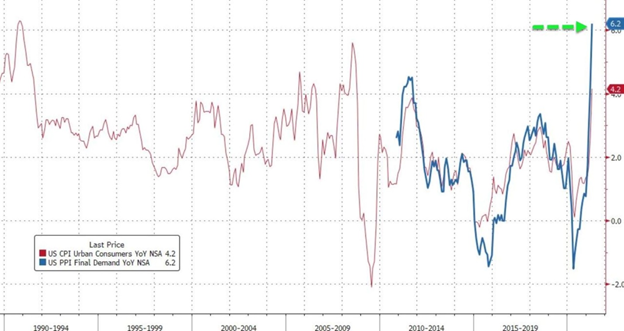

Producer prices surged the most on record in April, a year-on-year increase of 6.2%, beating expectations of 5.8%.

Source: Bloomberg via Zero Hedge

Source: Bloomberg via Zero Hedge

“There is more inflation coming,” Zero Hedge quoted Luca Zaramella, chief financial officer at Mondelez International Inc. Speaking on the food and beverage maker’s April 27 earnings call, she added “The higher inflation will require some additional pricing and some additional productivities to offset the impact.”

The US Federal Reserve has already said it will tolerate inflation above the normal 2% target, and let the economy run hotter before stepping in to cool it with rate hikes.

China

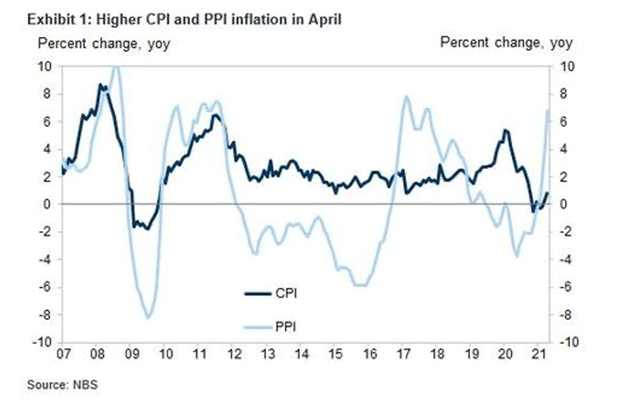

Adding to inflation worries is what’s happening in China. The Chinese economy has led the world in growth, being the first to emerge from the pandemic. Like in the United States, however, the recovery after months of strict lockdowns in cities like Wuhan, the epicenter of the virus, is pressuring prices.

Chinese exports rose sharply in March and imports grew to the most in four years, suggesting improved global demand amid worldwide vaccination programs.

After months of deflation (falling prices) China’s producer price index (PPI) rose 4.4% in March, the most since July 2018, as the cost of oil, copper and agricultural goods rallied. As the world’s biggest exporter, China’s rising prices threaten to stoke inflation around the world.

Its factory gate prices climbed more than expected in April while the PPI rose 6.8%, the most since October of 2017.

Going hungry

The global food price increases are clearly of most concern, especially for seniors living on fixed incomes, the poor on social assistance, and the working poor getting by paycheck to paycheck.

For the most vulnerable, not only is food getting more expensive, in some places, it has become less available.

The Guardian reported that people living in poverty around the world are in danger of food shortages as the coronavirus continues.

“Food systems have contracted, because of Covid-19. And food has become more expensive and, in some places, out of reach for people. Food is looking more challenging this year than last year,” the British newspaper quotes Agnes Kalibata, special envoy to the UN secretary general for the food systems summit 2021.

She noted the main impact of covid has been the shutdown of food markets, which has made it very difficult for farmers. Africa was worst hit, with several countries experiencing serious food prices and shortages, made worse by a drought in East Africa affecting northern Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia.

The Guardian reports that many underlying problems have grown worse over the past year, as people have exhausted their reserves of food, cash and family support and now are facing a long crisis without backup.

“We are facing a greater threat this year, as economies have shrunk,” she said. “That is happening across the globe, everywhere. Countries are in a very distressed situation, and it is not getting easier – it is getting more difficult. Some countries have hung on, but for how long?”

Kalibata’s thoughts are confirmed by the World Bank, which in a May 7 briefing note, states that COVID-19 impacts have led to severe and widespread increases in global food insecurity, affecting vulnerable households in almost every country, with impacts expected to continue through 2021 and into 2022.

Other observations in the note include:

- Higher retail prices, combined with reduced incomes, mean more and more households are having to cut down on the quantity and quality of their food consumption.

- Numerous countries are experiencing high food price inflation at the retail level, reflecting lingering supply disruptions due to COVID-19 social distancing measures, currency devaluations, and other factors. Rising food prices have a greater impact on people in low- and middle-income countries since they spend a larger share of their income on food than people in high-income countries.

- Rapid phone surveys done by the World Bank in 48 countries show a significant number of people running out of food or reducing their consumption.

- As of April 2021, the World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that 296 million people in the 35 countries where it works are without sufficient food — 111 million more people than in April 2020.

Us ‘mega-drought’

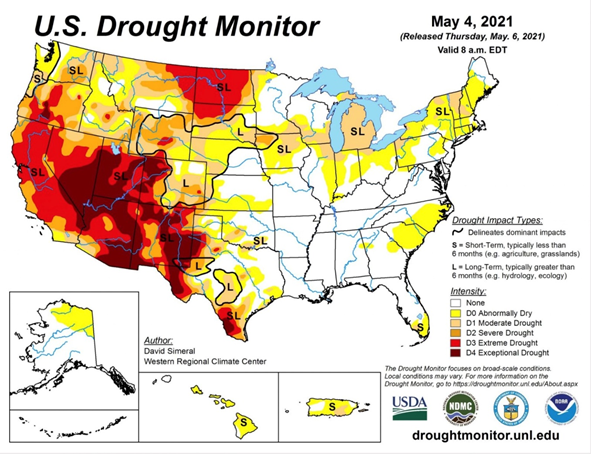

Back to supply chain issues in the United States, one of the most serious factors likely to worsen higher food prices is the major drought engulfing much of the western US.

Last year a team of scientists reported that the current “mega-drought” in the region, lasting nearly two decades, is as bad or worse than any in the past 1,200 years.

As of May 6, 67% of the US West was in a state of “severe” drought, and 21% is already in “exceptional drought”, the worst category out of six in the US Drought Monitor’s framework.

The states most at risk are southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and Utah. In California, where over a third of the country’s vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts are grown, 90% is experiencing drought conditions — an alarming statistic considering the state last year had its worst fire season in history and just saw its second consecutive dry winter, with most areas 75% of normal snowpack.

It’s only May, the amount of extreme and exceptional drought is unbelievable.

It’s only May, the amount of extreme and exceptional drought is unbelievable.

According to National Geographic, tree rings from northern Mexico and the US West present a record that goes back to around 800 AD. In that 1,200-year span, the region experienced 35 major droughts and four mega-droughts. Most Americans probably identify the 1920s Dust Bowl as among the nation’s worst, but that drought only lasted five to 10 years. The current dry stretch started in 2000 and hasn’t let up, putting it second only to a highly arid period in the last 1500s.

Climatologists who analyzed the data say the drought would have been bad from natural causes anyway, but the addition of climate change pushed it into extreme territory. Global warming has bumped average temperatures in the American West up 1.6 degrees F since the early 1900s.

Temperatures in California’s Central Valley to southern Arizona are expected to climb into the 90s and above 100 in many places Thursday and Friday — not record-breaking but much higher than normal for mid-May.

The problem this year has been made worse by the La Nina weather phenomenon, that began last fall. In a La Nina year, a cooling of Pacific Ocean surface waters shifts precipitation-rich weather patterns northward, making them miss the US Southwest.

Looking at the country as a whole, the US Department of Agriculture says drought coverage across the US continues to approach record levels.

“There have only been four times in the history of the drought monitor that we have seen more than 40% U.S. drought coverage as we come into early May,” KIWA Radio quotes USDA meteorologist Brad Rippey. “The current U.S. drought coverage is 46.6% of the lower 48 states in drought. That is a 2.6% increase from what we saw five weeks ago.”

As farmers tend their fields for this year’s growing season, 26% of US corn production is in drought, 22% of the soybean crop faces dryer than normal conditions, 35% of winter wheat is in drought, 33% of sorghum and 31% of cotton.

As of May 4, 36% of US cattle production areas were showing drought, while hay producing regions are looking at 33%.

Water concerns

The two decades-long dry spell is taking its toll on western US water supplies. Not only is the area receiving less rainfall, good for filling lakes and streams, the snowpack is far lower.

Folsom Lake in California, normally fed by melting snow in the Sierra Nevada mountains, this year is only half full. Lake Mead, one of two major reservoirs in the Colorado River basin, on which 40 million Americans depend, is reportedly creeping towards a water level minimum that would trigger the first official shortage declaration for the basin.

With Mead just 39% full, the Bureau of Reclamation expects a water conservation plan to be implemented in June. Water allotments to the states that draw from the lower part of the river, like Arizona and Nevada, would see major cuts.

Farmers are bracing for another season of tight water supplies.

In the Klamath River basin along the California-Oregon border, levels are so low that farmers will receive only 8% of the water they usually get, reports National Geographic, adding that local tribes are concerned they won’t have enough water to keep salmon populations healthy.

Less water and warmer temperatures in California’s rivers and reservoirs led the state to concoct a plan to truck 17 million smolt to San Francisco Bay from various hatcheries, an emergency step not taken since the last major drought in 2014, Reuters reported on Thursday.

California Governor Gavin Newsom has declared a drought emergency in 41 of 58 counties, which according to Modern Farmer, comes with a huge reduction in the amount of available water for agriculture in the region—primarily grapes in wine country…

[W]arnings have been sent to tens of thousands of water rights holders, asking them to start conserving water. For farmers, this likely means that what water remains will be used to maintain perennial crops like fruit and nut trees, rather than planting usual annual crops like vegetables.

Darker times ahead

Without life-giving bands of precipitation to wet parched soil, US farmers are expected to go through another rough growing season.

Lower crop yields mean higher prices for agricultural commodities. Food producers see their margins squeezed by higher input costs and pass these onto consumers.

A higher-income household can shrug off a 5, 10, even a 20% increase in grocery prices. Not so for families and individuals whose grocery budgets are tighter than a shrunken orange peel.

As incomes rise, households spend more on food but it represents a smaller share of their overall budget. Lower-income people don’t have room in their budgets for much other than food and shelter.

According to the USDA, in 2019 the poorest households spent an average 36% of their disposable income on food, compared to the 10% that most Americans spend.

With the difficulties covid-19 has placed on grocery supply chains, 2020’s figure is expected to be higher. Some are predicting the percentage of disposable personal income the average US household spends on food will reach 40%, with poorer families having to spend well over 50%.

As stated earlier, the prices of many agricultural commodities including corn, wheat and soybeans, are going haywire amid supply disruptions and robust demand. This past March, pork chops and chicken breasts were both up 10%, while the prices of eggs and cheese increased 6% compared to a year earlier.

The latest inflation data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the largest month-to-month CPI increase in almost nine years.

The Economic Collapse blog takes this a step further by pointing out that the bulk of the stimulus spending the Biden administration has promised, has yet to be rolled out, meaning inflation is likely to get a whole lot worse:

Almost everybody loved it when the federal government started sending out big, fat stimulus checks.

But you aren’t going to love it when a cart of food costs you $400 at the grocery store.

Whenever the government hands out “free money”, someone has got to pay for it, and one way we are paying for it is through higher prices.

If you do not believe that this is a major national crisis yet, you will soon, because it won’t be too long before most of the country is loudly complaining about how nightmarish inflation has become.

Another commentary notes that “the [covid] war is far from over,” with 100 countries yet to receive a single vaccine shot, some vaccinated countries still seeing cases surge, and global supply chains likely to remain disrupted for a long time.

Michael Every of Rabobank thinks we could even be looking at price controls such as occurred during the 1970s when government put restrictions on the amount that wages and prices could increase, or Second World War-era rationing.

It all points to a pretty grim picture.

Conclusion

Nobody wants to see hyper-inflation in North America, where stable prices are the norm, or anywhere else for that matter, but the risk is certainly there.

US food price increases are already at their highest in nine years, and the consumer price index rose the most in April of any 12-month period since 2008.

The situation is particularly bad in the US Southwest which is experiencing the continuation of a 20-year drought that is the worst in 1,200 years.

Among the crops already seeing drought conditions are corn, soybeans, wheat, sorghum and cotton. Hay crops and cattle production are also expected to be hit hard.

A lack of snow-melt runoff and precipitation, in an El Nina year made worse by climate change, has left reservoirs at a fraction of their normal levels, endangering millions of people that depend on them including farmers and ranchers that need to irrigate crops/ water herds.

California has already declared a drought emergency in nearly three-quarters of the state, and an official water shortage declaration for the Colorado River basin is expected by June.

Continuing the US (and Canadian) economic recovery is obviously important but it should not come on the backs of the poor who bear the most weight of inflation, particularly increases in food prices.

Government officials need to be aware of how their monetary and fiscal policies are impacting the most vulnerable in society.

Richard (Rick) Millsaheadoftheherd.com