Thanksgiving brings to mind not only turkeys, family, and friends, but also should help us recall the remarkable ideas and philosophies that helped shape, and indeed were, the foundation for the United States of America as a Republic.

In that spirit, we will forgo for this week the series we have been exploring on cycles and the examination of budgets and deficits, debt and taxes, and the future crisis they will bring if not dealt with. Rather, let’s reflect on what we want our world to look like after that crisis. What should be our guiding principles?

Most of us are aware that the founding fathers read Locke, Hume, Smith, et al. But not many of us are aware that there was another series of papers that were just as influential as the works of more famous philosophers. They were clearly a part of the background for the Federalist Papers and, later, our Constitution.

My friend Joe Lonsdale, most well-known for his prodigious and successful venture capital efforts (Palantir, Anduril, Oculus, software, healthcare, etc.) and founder of 8VC, which manages $6 billion in early-stage startups, also writes and hosts a podcast on a wide range of topics. Joe interviews the Who’s Who of the tech world, politics, and more, as well as writes his own posts.

He also founded The Cicero Institute, a pro-liberty think tank and activist group focused on changing things at the state level. They have been very successful.

This week, he writes about Cato’s letters, a series of 144 writings published between 1720 and 1723 in London on government and corruption and what is necessary for republics to succeed. They were very influential in pre–Revolutionary War America. He has kindly given me permission to use his work for this week’s letter.

Now, let’s think about what we want our country to look like, to act like, after we solve the coming crisis.

Cato’s Letters: The Rules for Republics

By Joe Lonsdale

In Revolutionary America, colonists read Cato’s Letters for its rousing lessons on liberty, power, tyranny, and republican government.

If you were to attend an average American history course today, you’d be lucky to pick up on any principles behind the American Revolution beyond unjust taxation and perhaps opposition to monarchy. If you were unlucky, you might hear fantastical reasons like white supremacy and slavery, as posited in the radical revisionist “1619 Project.”

One thing you would struggle to find is any mention of the most popular political work of the late-colonial period that educated colonists knew and could often quote: Cato’s Letters.

2023 marks the 300th anniversary of the publication of the collection of 138 pseudonymous letters in English newspapers. They were penned in response to public outrage over the South Sea Bubble and were influential in British politics and in the colonies.

Authors John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon chose the Roman statesman and Stoic Cato the Younger (95–46 BC) as a pseudonym because of his strong opposition to corruption in the Roman Republic. In his final days during the Civil War, he committed suicide rather than surrender to Julius Caesar, whose tyrannical claims Cato opposed.

The South Sea bubble was an early instance of government-corporate cronyism. In 1711, the South Sea Company was formed as a speculative venture to exchange England’s nine-million-pound national debt for shares in the company. The company’s purported value was based on a monopoly granted by Parliament to trade in the Spanish colonies of the New World and a license to provide African slaves to those colonies.

The company never turned a profit, nor could it even make interest payments, but company leaders, speculators, and even British royals drove the price of the stock in 1720 from £125 to £950 in just six months through intense speculation. When the bubble burst, share prices fell to £185, many lost huge sums, and the debt had to be exchanged once again into the national bank and other public financial institutions.

Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme, William Hogarth

Trenchard and Gordon recognized the South Sea Bubble not merely as a financial crisis, but a crisis of political corruption and lack of public spirit: government leaders had colluded with financial manipulators on a huge racket and betrayed the public trust. If that sounds familiar, you’ll understand why I want my fellow citizens to revisit the letters with me. The acts of government-corporate collusion and mischief take different forms today, but the underlying problems are largely the same. Below, I share some key lessons for our current age.

Note: unless otherwise noted, “Cato” refers to Trenchard and Gordon, the authors of the 18th-century letters, not the ancient Cato Younger

On Accountability and the Law

“It is nothing strange that men, who think themselves unaccountable, should act unaccountably, and that all men would be unaccountable if they could.”

Like his predecessors, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, Cato begins his analysis of the state with the social contract. Before governments existed to make and enforce laws, there were two fundamental laws grounded in nature that governed human societies: the law of equity (to not harm one another) and the law of self-preservation (to defend yourself).

Given the difficulty of maintaining this order—don’t hurt others, defend yourself—people come together to form governments to rule and benefit themselves. In agreeing to a social contract, people give up some of their individual authority and empower some others to enforce the rules. When rulers assume greater authority, they must also assume greater accountability.

Cato points out that while the social contract had been intended to ease life in the state of nature, it also could empower corrupt rulers: “human society had often no enemies so great as their own magistrates; who wherever they were trusted with too much power, always abused it…” For Cato, this was not surprising; it was simply part of human nature.

Cato suggests that it is “as frivolous as it is wicked” to imagine that the fear of God would restrain a wicked ruler. So, power must be checked, and rulers must be accountable to citizens, be they kings, presidents, or consuls. In the United States, we have no king, but who are the leaders who evade accountability while wielding power? Congress? The President?

Neither. Our most unaccountable leaders are those in the regulatory and administrative state, the vast apparatus of bureaus and agencies created democratically by Congress but which have turned into powerful political institutions in their own right. These are the institutions that make citizens small and corrupt interests large. Cato could not have foreseen the modern regulatory state, but he still provides guidance on how to wrangle it.

In Letter 8, he presents the case of monopolies under Queen Elizabeth I. When she learned that some of her advisors had tricked her into granting them monopolies on certain commodities for their own profit, she publicly apologized and acknowledged her wrong judgment—and then delivered the guilty within her court up to justice. The queen’s solution to corruption was also Cato’s: severity in the defense of liberty.

Cato explains that the peace and security of a society are maintained through the twin forces of “the terror of laws, and the ties of mutual interest.” We know these tools proverbially as the carrot and the stick, and Cato stresses that the impulse toward self-preservation, or self-love, drives people to pursue the carrot and avoid the stick. But strong leaders must be willing to escalate and use constitutional power—the stick.

“To spare the meek and to vanquish the proud; to pay well, and hang well, to protect the innocent, and punish the oppressors, are the hinges and ligaments of government, the chief ends [of] why men enter into societies.”

The law for Cato had the two-fold purpose of encouraging virtue and discouraging vice. Good government and happy people are found where “the laws are honestly intended, and equally executed.” Healthy societies cannot have double standards for public officials and corporations. In such a society, honest citizens and dishonest officials would be treated in the same manner.

Cato was especially concerned about the abuses of power perpetrated by public officials because of their power of influence over society. And he was adamant that the crimes of private citizens were not comparable to those of public officials because “the first terminate in the death or sufferings of single persons; the other ruin millions, subvert the policy and economy of nations, and create general want, and its consequences, discontents, insurrections, and civil wars, at home; and often make them a prey to watchful enemies abroad.”

On Virtuous Self-Interest

“We do not expect philosophical virtue from [men]; but only that they follow virtue as their interest, and find it penal and dangerous to depart from it.”

Cato takes a realist view of human nature. And since both virtue and vice are propelled by the same root force in human nature, Cato doesn’t think in terms of improving human character. He considers it a fool’s errand to try to change human nature, to make it more virtuous or less passionate. In fact, it’s just this nature within us that can be harnessed to improve our society.

As noted above, he encourages this first through law. But the second force is wealth and its honest pursuit through capitalism. Self-interest and capitalism allow every man to provide for himself by providing for others and providing for others as he provides for himself.

Cato explains that people “are never satisfied with their present condition, which is never perfectly happy; and perfect happiness being their chief aim, and always out of their reach, they are restlessly grasping at what they never can attain.” This is our nature and not something to be fixed by Marxist schemes against capitalism or acquisitiveness. Neither wealth nor poverty are measures of moral superiority. It is possible to despise wealth and shun power because of disinterestedness “created by laziness, pride, or fear; and then it is no virtue.”

It is no virtue indeed to despise wealth in itself. It’s paradoxical but true that “the best actions which men perform often arise from fear, vanity, shame, and the like causes.” So rather than attempting to make men perfect and build a utopia, Cato advises that laws be framed in such a way as to spur human ambition, incentivize virtue, and punish vice.

On the Danger of Luxury

“Pleasure succeeded in the room of temperance, idleness took the place of the love of business, and private regards extinguished that love of liberty, that zeal and warmth, which their ancestors had shown for the interest of the public; luxury and pride became fashionable; all ranks and orders of men tried to outlive one another in expense and pomp; and when, by so doing, they had spent their private patrimonies, they endeavored to make reprisals upon the public; and having before sold everything else, at last sold their country.”

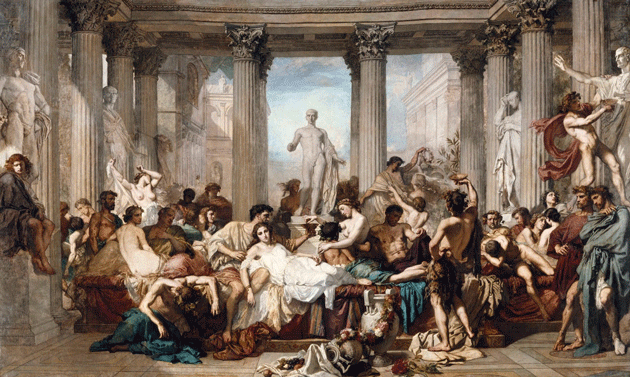

The Romans in their Decadence, Thomas Couture

While Cato praised virtuous self-interest, he also identified the obsessive desire for luxury as a danger to society. This was hardly a new idea in Western canon, but these ideas are constantly being forgotten. That was certainly the case in the lead-up to the South Sea Bubble.

Millennia before, Rome’s stable society and republican government atrophied as its leading citizens sought opulence. Wealth itself was not the problem, but rather a culture of narcissism that drove people to seek wealth in order to lavish it on their personal whims, rather than put it to productive use.

Rome became a republic of softness and indulgence. Public interest was replaced by self-serving narcissism, and vices took the place of virtues. People wanted to enjoy the fruits of labor without the hard work, and each was jealous of those who had more. It bears remembering that “republic” comes from the Latin res publica, meaning “the common matter,” and republics depend on a public spiritedness to unite citizens in a zeal for liberty and the republic itself.

As the leading Roman citizens and politicians pursued their private whims, they set the tone for citizens of every rank to do the same. A mimetic cycle ensued by which everyone sought to live more grandly than the next. Both the great and the humble turned in on their own interests and abandoned interest in the republic they shared responsibility for in common.

In some instances, Roman statesmen literally prioritized their own fishponds as the republic fell apart. Read more about that in “Fishponds and Fighters.”

On Public Spirit

“‘Twas in vain to think of bribing a man, who supped upon the coleworts of his own garden. He could not be gained by gold, who did not think it necessary. He that could rise from the plough to the triumphal chariot, and contentedly return thither again, could not be corrupted.”

The civilizations that Cato valorizes—Rome and Sparta among them—were societies in which virtue, honor, and public spirit were prized far above wealth. In these societies, men could be honorable and poor. Cato uses the example of coleworts to describe the ultimate simple but admirable lifestyle in antiquity. Today, we call this leafy vegetable “kale.”

When men’s honor came as a reward for their virtue, virtue became popular and sought after in society. Rulers ought to be interested in making their people virtuous, as the virtuous are governable, good citizens, but wicked rulers strategically introduce vice in order to debauch their subjects so that they will quietly bear the yoke of tyranny.

The Roman poet Juvenal coined the phrase “bread and circuses”—panem et circenses—to describe how cynical leaders might feed and entertain subjects to pacify them. The opposite of bread and circuses might be “coleworts and chariots”—men who could feed themselves and ride into battle themselves, not for entertainment, but for honor.

Wealth, ease, and grandeur had replaced honor and virtue as social capital. Cato writes that “The Roman virtue and the Roman liberty expired together; tyranny and corruption came upon them almost hand in hand.” Officials who accepted bribes or enriched themselves at the expense of the public trust forsook a value that we speak little of today: public spirit.

Cato defines public spirit as love of one’s country—we’d say “patriotism”—and the term recurs throughout the 138 letters. He writes:

“This is publick spirit; which contains in it every laudable passion…it is the highest virtue, and contains in it almost all others; steadfastness to good purposes, fidelity to one’s trust, resolution in difficulties, defiance of danger, contempt of death, and impartial benevolence to all mankind. It is a passion to promote universal good, with personal pain, loss, and peril: It is one man’s care for many, and the concern of every man for all.”

Cato himself admits that the notion may be antiquated, “too heroic, at least for the living generation” of the eighteenth century, but public spirit summarizes the qualities required to be part of a res publica, a republic. Republics have citizens, not subjects, and besides their obligation to self-preservation, citizens have duties to each other and the common good.

Without that spirit, tyrants inevitably fill the void.

Trenchard and Gordon died well before the Declaration of Independence in 1776, which their work helped to propel. The Founders and Framers heeded their lessons on public corruption, the importance of accountability in the state, and the importance of freedom itself. In James Madison’s first draft of the 1st Amendment, he paraphrased Letter 15.

Cato: Freedom of speech is the great bulwark of liberty; they prosper and die together: And it is the terror of traitors and oppressors, and a barrier against them.

Madison: The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.

We Americans should be wary of anyone who would attack the pillars of our republic—the honest pursuit of wealth, the spirit of patriotism, and the rule of law, including the “great bulwarks of liberty.” These are worth fighting for.

The Liberty Fund has published a two-volume edition of Cato’s Letters and made the text freely available online. I would encourage anyone to read them for many more lessons.

***

Dallas, Sushi, and South Africa

John here. I am writing this week’s letter early as everyone at the company is on holiday this long weekend. As it should be. I will shortly go to buy groceries for Thanksgiving dinner: prime rib, mushrooms, and spinach. My niece’s husband is smoking four turkeys. The rest of the kids are bringing their favorites. Eight kids plus significant others and family, and I hope at least seven of nine grandkids show up. Around 40, so not too large this year.

And since we just read Joe Lonsdale’s letter, it seems appropriate to follow it up with a little story. I was in Austin two weeks ago and emailed Joe to ask if he’d like to get together. He said he had one spot at a table for sushi that evening. I immediately said yes. It was a few miles from the hotel I was staying at, but Uber said it was a 30-minute ride. It took every bit of that. I was dropped off in an older part of town, in front of a small older home. Right address, but no sign and nothing to let me know there was a sushi restaurant anywhere close. I walked up and down the street and then came back to the house and walked to the back, seeing nothing. Finally, someone came out, and I asked them where Sushi ATX was. He said through that back door. Clearly, you had to know where you were going.

I walked into a small and crowded room, where the 12 people that I would be having sushi with were gathered. A very interesting crowd: private equity from Singapore (and an expert on sake, who gave me a running commentary on what I was tasting), one of the first hires at SpaceX now running his own space venture, and so on.

Sushi ATX is what is called an omakase experience. There are just 12 seats at the sushi bar and 15 courses of sushi, plus at least six flights of sake paired with them. It was part theater, but the total focus was on providing riffs on traditional sushi. Seasonings and sauces delicately brushed on each piece, sometimes scorched, and pairings that I would never have been able to imagine, let alone think I would want. But every piece was amazing. It was clearly one of the top culinary experiences of my life, if not the top. I am told the place has a two- to three-month waiting list. I just got lucky. While it was pricey, the priceless part was getting to sit next to Joe for two uninterrupted hours. What an education. And fun!

As promised last time, here is a link to info on my fishing trip. I hope you’ll be able to join me.

With that, it’s time to hit the send button. And in the spirit of the season, I am thankful for you and the precious gift of your time and attention. It means a great deal to me. I do my best to not waste it.

As you read this, I will be back in Dorado Beach, wishing I had leftover smoked turkey for sandwiches. Have a great week!

Your musing on the strange twists and turns of life analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.