If you needed upwards of 50 million tonnes of copper over the next five years, and had very little production of your own, what would you do?

I’m thinking you would manipulate the market like crazy trying to get everyone to believe there is a huge surplus instead of a major deficit.

How would you do it? Well, we can look at the last time the Chinese manipulated the copper market. In March 2015 they found every analyst they could and invited them to China. The group was shown a few warehouses stacked with copper to the rooftops. There was so much copper the ground was compacting, said one analyst. Another said the stacks were falling over like dominos. The world bought the surplus story, swallowed it hook line and sinker. Headlines screamed ‘China has enough copper!’

Of course it wasn’t true. China needed copper, and what they had, all of 2 million tonnes, was tied up in financing deals. At any one time there are at least 1 million tonnes in transport, or somewhere in the supply chain that has already spoken for, ie., not available.

The world continues to get conned. Every year so-called “experts” predict a surplus; instead what happens? Deficit after supply deficit.

(the copper market in December 2020 showed a 24,000-tonne surplus compared to 93,000-tonne deficit in November, according to the International Copper Study Group. Demand in 2021 is expected to outstrip supply leading to a potential deficit of at least 200,000 tonnes)

Let’s expose the con job.

Copper consumption

China is spending huge amounts of money on infrastructure, especially their power grid. The country’s “new infrastructure” construction projects including a massive 5G rollout, and spending on electric vehicle charging stations, are expected to require 150,000 tonnes of copper, according to Bloomberg Intelligence data quoted by China Daily.

India, to become competitive, needs to modernize its power grid; so too does Indonesia, they have to build all those smelters for in-country beneficiation of ore.

Africa is expected to drive global growth over the next several decades, as populations there climb, but dwindle elsewhere.

“About half of the world’s fastest-growing economies will be located on the continent, with 20 economies expanding at an average rate of 5% or higher over the next five years, faster than the 3.6% rate for the global economy,” Brookings’ Africa Growth Initiative wrote in its 2019 ‘Foresight Africa’ report.

According to the Center for International Policy, in 2035 the number of working-age people in Africa will exceed the rest of the world combined, and by 2050 one in four humans will be African. At 2100, 40% of the world’s population will hold a passport from an African country.

Per capita consumption of copper in developed countries like the United States, Canada and Japan, is currently around 10 kilograms per person. Current US per capital copper usage is 12 kg, according to the Minerals Education Coalition.

Copper consumption in Korea in 1965 was less than 1,000 tons. By 1995, Korea’s consumption of copper had reached 637,000 tons, or more than 14 kg per person.

In China, even after years of economic growth, per capita copper usage was just 7.1 kg in 2013 (the latest year I could find). As China’s populace urbanizes, builds up its infrastructure and becomes more of a consuming society, there is no reason to suspect Chinese copper consumption won’t approach or even surpass US, Japanese and South Korean levels. There are 1.39 billion people in China, even a slight increase in Chinese consumption will translate into enormous demand growth.

India, with its 1.36 billion people, is presently using just 0.4 kg of copper per person. The country is modernizing and needs to invest heavily in electrical power infrastructure. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), India’s power production will need to rise by up to 20% annually to keep pace with its economic and population growth. Just meeting the required power target would double India’s annual copper consumption.

The Indian government, led by Narendra Modi, is focusing on Asian partners China and Japan for enhancing investments in infrastructure and manufacturing. The growth model pursued by China and Japan — export-oriented manufacturing, heavy infrastructure building and urbanization — has become India’s blueprint for pushing growth up to and beyond the 7% mark.

Population growth

Currently there are well over 7.6 billion people living on this planet; an urbanization rate of 53% means there are roughly 3.71 billion urbanites in the world today. It has been estimated that by the year 2050 our global population will reach 9.6 billion. If it does, and if an expected urbanization rate of 70% is achieved, 7 billion people, or almost the equal of today’s current world population, will be considered urban.

Could we hit the 10 billion people mark? Could 70% of us be living in cities by 2050? The answer is likely yes. Developing countries are responsible for 90% of current population growth — these are on average very young people with many years of reproductive life left. By 2025, in just four short years, 84% of the world’s people will live in developing regions.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) “Almost all urban population growth in the next 30 years will occur in cities of developing countries. Between 1995 and 2005, the urban population of developing countries grew by an average of 1.2 million people per week, or around 165 000 people every day. By the middle of the 21st century, it is estimated that the urban population of these counties will more than double, increasing from 2.5 billion in 2009 to almost 5.2 billion in 2050.”

The developing world’s urban centers are expected to burgeon, drawing 96% of the additional 1.4 billion people by 2030. Due to the overall growing global population — but especially an exploding urban population (urban populations consume much more food, energy, and durable goods than rural populations) — demand for water, food, housing, heat, energy, clothing, and consumer goods is going to increase at an astounding rate.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) the consumption of metals typically grows together with income until real GDP per capita reaches about $15,000 – $20,000, as countries go through a period of industrialization and infrastructure construction.

A few countries stand out as well below the IMF’s $15,000:

- Indonesia – $11,812

- Philippines – $8,908

- India – $6,700

- Pakistan – $4,690

Since they are still a considerable distance from the point where further increases in GDP per capita no longer increase copper consumption per person, Indonesia, the Philippines, India and Pakistan (and the other 113 out of 180 countries listed below the IMF’s $15,000 cut-off) will likely continue to add significantly to global copper demand for some time to come.

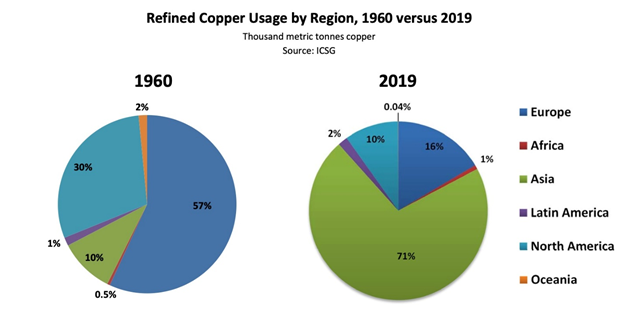

Source: World Copper Factbook 2020

Source: World Copper Factbook 2020

Tomorrow’s copper demand

Copper’s widespread use in construction wiring & piping, and electrical transmission lines, makes it a key metal for civil infrastructure renewal.

A report by Roskill forecasts total copper consumption will exceed 43 million tonnes by 2035, driven by population and GDP growth, urbanization, and electricity demand. Total world mine production in 2020 was only 20Mt.

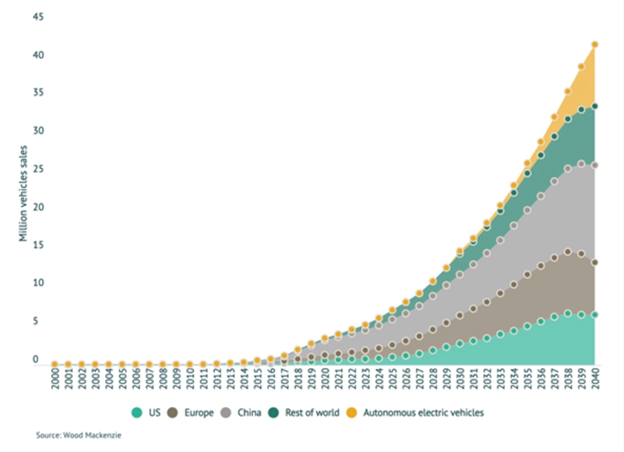

The continued movement towards electric vehicles — including cars, trucks, trains, delivery vans and e-bikes — is a huge copper driver. EVs use about four times as much copper as regular internal combustion engine vehicles.

Electric vehicle sales, 2000-2040. Source: Wood Mackenzie

Electric vehicle sales, 2000-2040. Source: Wood Mackenzie

Copper parity

We already have one billion people out of today’s current population slated to become significant consumers by 2025.

Another 2 billion people will be added to the world between now and 2050. Most will not be Americans but they are going to want a lot of things that we in the Western, developed world take for granted — electricity, plumbing, appliances, AC etc.

“Infinite growth of material consumption in a finite world is an impossibility.” — E. F. Schumacher

“We’re living in a finite world, one in which resource constraints are becoming increasingly binding.” — Paul Krugman, ‘The Finite World’

What if all these new one billion consumers were to start consuming, over the next 10 years, just like an American? What’s going to happen to the world’s mineral resources if one billion more ‘Americans’ are added to the consuming class? Here’s what each of them would need to consume, per year, to live the American lifestyle…

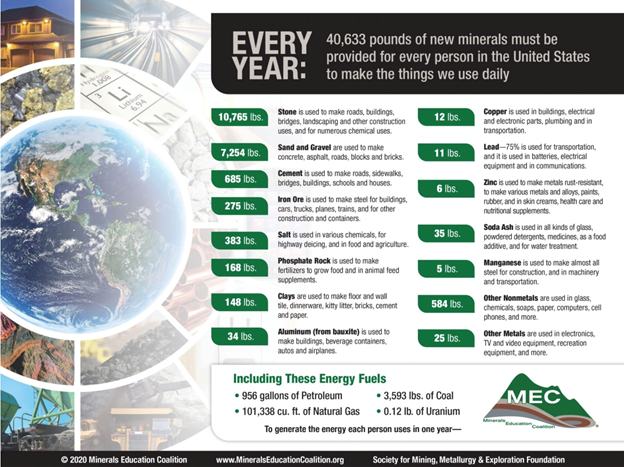

In 2020, 40,633 pounds (20.3 tons) of minerals and fuels were needed per person to maintain the American lifestyle.

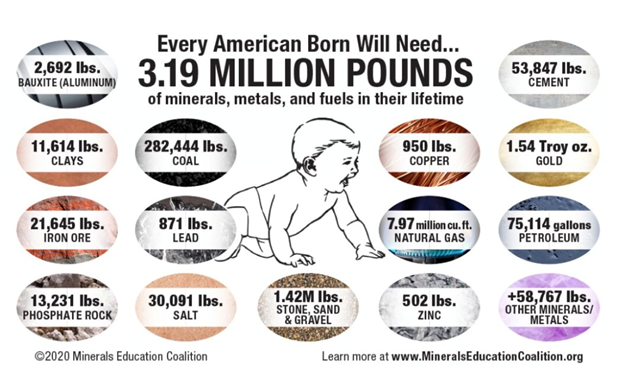

According to the Minerals Education Coalition every American will need 950 pounds (430 kg) of copper over their lifetime.

2020 US per capita use of minerals

2020 US per capita use of minerals

One billion new consumers by 2025. Can everyone who wants to, live an American lifestyle? Can everyone everywhere else have everything we in North America have? The answer is a resounding no!

Even if we mined every last discovered, and undiscovered, pound of land-based copper, the expected 8.1 billion people in the developing world by 2050 would only get three quarters of the way towards copper use parity per capita with the U.S.

Of course the rest of us, the other 1.5 billion people expected to be on this planet by 2050, aren’t going to be easing up, we’re still going to be using copper at prestigious rates while our developing world cousins play catch-up.

Copper use parity isn’t going to happen, it can’t.

Despite what mainstream analysts say, copper is already in a very real, structural supply deficit. Most just don’t know it.

Let’s state the obvious:

- For over the last 16 years supply has struggled to keep pace with demand.

- Metal supply is finite and subject to compounding demand from developing nations.

- Metal production is highly cyclical, with intermittent peaks and troughs which are intricately linked to economic cycles. Declining production has historically been driven by falling demand and prices, not by scarcity.

- Rates of production and reserve amounts continually change in response to market movements and technological advances.

- If energy was cheap and unlimited, recoverable resources would be unlimited.

But

- Discovery and development is increasingly becoming more challenging and expensive.

- Average ore grades are in decline for most minerals, yet production has increased dramatically.

- Our most important metals are suffering from declining ore quality and rising extraction costs.

- Our prosperity has always been based on the fact that producing resources yielded more resources than costs. However the cost of energy and the amount used are climbing but the returns from energy expended is declining. Eventually the quantity of resources used in the extraction process will be 100% of what is produced.

- Most older mines, the foundation of our supply, have increasing costs, with production rates stagnating or even declining.

- The rate of discovery is not keeping pace with the rate of depletion, let alone being higher.

Reserves

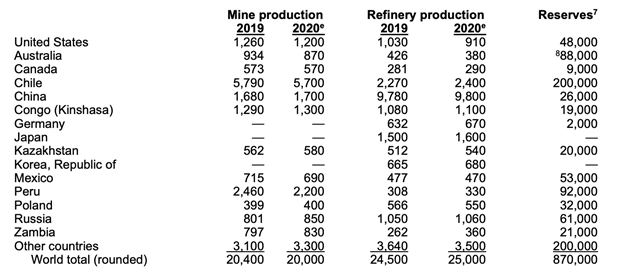

Each year, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) estimates the amounts of reserves: the quantities of mineral that can be economically extracted.

World copper reserves are currently placed at around 870Mt. When considered as just a single consolidated global number copper reserves seem large and adequate for several decades of production at 2020 levels.

Source: USGS

Source: USGS

Unfortunately, most people do not take into consideration that these reserves are made up of many separate deposits, each of which must be considered as standing alone, on its own merits.

The economic viability of the world’s copper deposits are influenced by many factors that inevitably reduce the amount of copper that reaches production.

These factors are:

- Location

- Capital and operating costs

- Market conditions

Each of these deposits is also subject to geological, engineering, environmental and political constraints that are always changing.

Many new mines do not come online on time. Also, operating mines can suffer production stoppages/slowdowns or move into lower-grade ore.

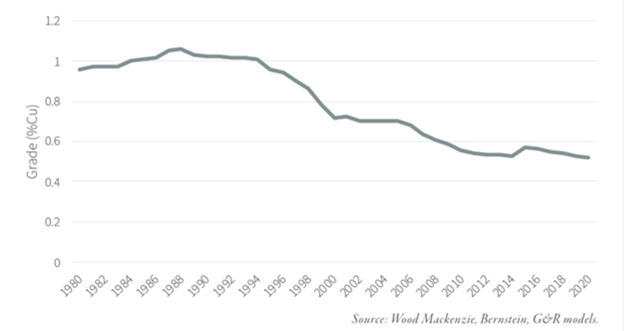

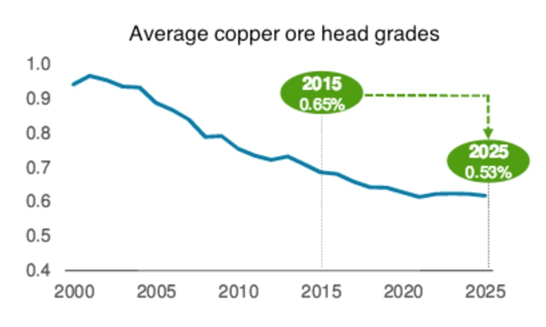

The metal content of copper ore has been falling since the mid 1990s. A miner now must dig up an extra 50% of ore to get the same amount of copper. As grade drops the amount of rock that must be moved and processed rises dramatically — all the while using more energy that costs several times more than it used to. With the lower ore grades now being mined, energy becomes more and more of a factor when considering mining economics.

A long-term structural trend became evident in the copper industry in 2005, when it began to suffer from depletion problems. Mineral depletion means a decline in both the quantity and quality of remaining mineral reserves.

Whereas in previous high copper price cycles, such as 1988 and 1994, miners could react to a higher price by increasing production from high-grade copper zones, by 2005 these easily accessible zones had all been mined out.

In a recent report, Goehring & Rozencwajg Associates found, after studying the various sources of the copper industry’s reserve additions, that very few new discoveries had been made. In fact, between 2001 and 2014, 80% of new reserves came from re-classifying waste rock into mineable ore, ie., lowering the cut-off grade.

Drawing from a database of 115 mines responsible for four-fifths of total output, the Wall Street natural resource investment house discovered the grade of new reserves each year has steadily declined, as a result of this practice.

In 2001, the new reserves grade was 0.80% copper but by 2012, it had fallen to 0.26%. The copper industry was still able to replace all the ore used in production with new reserves, but the quality of those reserves, ie., the grade, had dropped by nearly two-thirds.

Average grade of copper remaining reserve

Source: Energy & Capital

Source: Energy & Capital

A miner can only go so far in lowering the cut-off grade. At a certain point, it doesn’t matter how much the price rises, lowering the cut-off involves too many costs; mining then becomes un-economic.

Examples of such costs might be, the grades are simply too low, even at a higher price; the metallurgy becomes more difficult at a lower grade; trying to convert waste rock to reserves means going to a far-flung jurisdiction where there all kinds of added costs, like paying off a foreign government, or high royalties.

The report suggests the copper mining industry has gone as far as it can in lowering cut-off grades further, meaning it is no longer possible to add large amounts of reserves — especially given that porphyry deposits (from which 80% of global copper supply comes from) are typically low-grade, in the 0.3 to 0.4% Cu range. The industry, the report alludes to, is nearing its production peak.

Consider:

- From 2001 to 2015, the industry’s head grade — the average grade of ore fed into a mill — was 30% lower.

- Capital cost per tonne of annual production during the same period quadrupled, from $20,000 to $80,000 per tonne.

- Copper ore grades in new discoveries and development projects are declining. According to BHP, falling grades will remove around 2 million tonnes per year, or 10%, of global copper mine supply by 2030.

- Deposits are now being found at greater depths or in more remote areas, which cost more to extract.

- Copper reserve additions from a select group of 24 producers was cut in half, from an annual 27Mt in 2014 to 13Mt in 2020.

Chile is the world’s top copper producer, but the country is woefully short of power. The country’s power generation capacity currently stands at 19,742 megawatts. It is estimated that the country will need 56% more power to keep up with demand, which will come primarily from mining projects.

Also, because of a severe water shortage in the high desert, where most of the country’s major copper mines are located, water must be pumped from the ocean hundreds of kilometers to the mines 800m above sea level; of course the seawater must also be desalinated, an expensive process.

Chile’s mine workers frequently down tools to protest wages and/ or working conditions.

Last week 97% of workers in the union at BHP’s Escondida and Spence mines voted to reject the company’s contract offer, raising the risk of a strike at the two huge mines.

Also in Chile, the lower house this month approved a bill that would tax mining companies at a higher rate when the copper price increases. If passed by the Senate, miners would pay between 15% and 75%. The industry warns the new law, designed to collect more money for social programs, would stifle investment and make Chile less competitive.

The original text had a 3% flat tax on copper.

The Chilean government is being pressured by groups within its society to do more to address inequality. Triggered by the worst social unrest in a generation, the country reportedly has just elected an assembly that will place responsibility for writing a new constitution in the hands of the left wing.

The reforms could give more power to indigenous communities and expand water rights, including a potential ban on mining in areas where there are glaciers, along with increased state ownership of water desalinated by mining companies.

Demand to outstrip supply

According to S&P Global Market Intelligence, the current deficit in the copper market is expected to deepen over the next several years as supply struggles to keep up with robust demand from the power and construction sectors, as vehicle electrification accelerates.

“Beyond 2020, we forecast that consumption will outstrip production over the period to 2024, resulting in a growing refined market deficit and increasing copper prices,” states S&P Global Market Intelligence commodity analyst Thomas Rutland, in an October 2020 news release.

Fitch Solutions expects a shortfall of 489,000 tonnes in 2024 to rise to 510,000 tonnes in 2027.

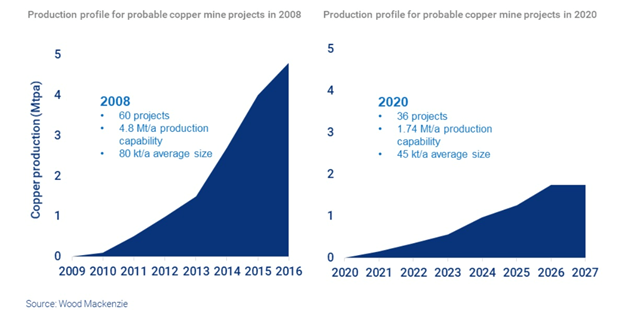

Commodities consultancy Wood Mackenzie projects out even further to 2040. The firm notes that mine closures and grade declines are ongoing features of the copper industry and that without additional investment in supply, production will decline from 2020 onwards.

In a March 2021 news release, Woodmac senior manager Julian Kettle writes that a shortage of projects threatens supply from mid-decade — a scenario that appears in the graph below.

Just prior to the global financial crisis in 2008 there were around 4.8 Mt of probable projects available to be developed. That equated to 30% of the existing market at the time, or approximately 10 years of growth. By comparison, there are currently just 1.7 Mt of probable projects, only enough to meet less than three years of demand growth.

Copper supply could be constrained by a shortage of advanced projects, says Wood Mackenzie.

Copper supply could be constrained by a shortage of advanced projects, says Wood Mackenzie.

Copper prices need to be significantly above marginal cost, in other words, prices need to stay high enough to provide miners with an adequate return on their investment for building today’s much more expensive and riskier new mines. There is also a significant additional cost in keeping production constant year over year.

If copper does not stay well above miners’ marginal costs the much-needed new mines will not be built.

Rio Tinto says growth will continue to be a challenge for several reasons:

- An increasing proportion of potential new supply is in riskier countries.

- More challenging environments with a lack of infrastructure imply an increase in the capital intensity of new projects.

- Recent supply has continued to underperform, with decreasing grades and disruptions impacting production.

- Major causes of supply disruption will continue, such as technical complexity, project delays and strikes.

Resource nationalism & political risk

Because the number of discoveries has been falling and existing deposits are being quickly depleted, resource extraction companies have had to diversify, away from geo-politically safe countries.

Resource nationalism is the tendency of people and governments to assert control, for strategic and economic reasons, over natural resources located on their territory.

A recent study pointed to 34 countries that have seen a significant increase in resource nationalism risk over the past year. Countries now rated “extreme risk”, according to the March 2021 report by Verisk Maplecroft, include major African copper producers Zambia and the DRC.

Reuters reports that 42% of global copper production is under political uncertainty right now, that could affect future production.

Conclusion

The world’s exploding population, the massive shift from rural to urban, the growth of a very consumption-minded middle class in developing countries, is all happening now.

Add in finite, increasingly hard-to-source resources.

The effects will be felt long before we start to run out of copper and there will be severe consequences:

- Rising energy and commodity prices

- A decline in the global economy

- Civil unrest

Perhaps the two biggest reasons to be bullish on copper are one, the massive costs and risks involved in finding and opening new mines in often geo-politically risky countries where a miner’s social license to operate is shaky at best.

And reason two concerns what is going on today regarding a loss of funding for junior exploration. A dearth of exploration capital in recent years is making it increasingly difficult for copper mining companies to replace their reserves. According to S&P Market Intelligence, the global exploration budget fell 11% in 2020 to $8.7 billion, mostly due to the covid-19 pandemic.

However an expected uptick in capital expenditures this year, driven by higher metals prices, is likely to reverse the situation.

Juniors able to advance their projects to the point where a major becomes interested are going to fare very well.

Are the coming consequences of living in a resource-finite world and not believing anything shallow-swimming analysts say about copper surpluses on your radar screen?

If not, maybe they should be.

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

Legal Notice / Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills has based this document on information obtained from sources he believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or completeness.

Expressions of opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any omission.

Furthermore, AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of the use and existence of the information provided within this AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you should conduct a complete and independent investigation before investing in any security after prudent consideration of all pertinent risks. Ahead of the Herd is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to buy any security.