Fifty years ago, on August 15, 1971, then-President Nixon interrupted “Bonanza,” one of the most popular TV shows of that era. To announce that he was ending the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold. Many consider it to be one of the most consequential decisions (WSJ, 08/09).

Fifty years ago, on August 15, 1971, then-President Nixon interrupted “Bonanza,” one of the most popular TV shows of that era. To announce that he was ending the convertibility of the U.S. dollar into gold. Many consider it to be one of the most consequential decisions (WSJ, 08/09).

President Nixon’s action of closing the gold window ended what was known as the Bretton Woods Monetary System, which had prevailed since the end of WW II.

The Bretton Woods Monetary system was the agreement of a conference from July 1 to 22, 1944 held in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States.

The conference, formally known as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, was a gathering of 44 nations. The conference also established the International Bank of Reconstruction and Development (now part of the World Bank) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The goal of the conference was to establish cooperation among countries to avoid the problems. Such as trade wars and competitive currency devaluations, which plagued the international environment.

The Operation of the Bretton Woods Monetary System

The Bretton Woods Monetary System was not a Gold Standard, in the purest form, but it was a Gold-Exchange Standard. US political and economic dominance necessitated the dollar being at the center of the system.

After the chaos of the inter-war period, there was a desire for stability, with fixed exchange rates seen as essential for trade. But also for more flexibility than the traditional Gold Standard had provided.

The Bretton Woods system drawn up and fixed the dollar to gold at the existing parity of US$35 per ounce. While all other currencies had fixed, but adjustable, exchange rates to the dollar (World Gold Council).

In the case of the Bretton Woods system, only other central banks enjoyed the conversion privilege; unlike the Gold Standard, the US did not exchange gold for dollars with private parties.

Other countries did not specifically commit to exchange their currencies for gold under Bretton Woods. There was no obligation on the US to limit its money supply to a fixed multiple of its US gold reserves.

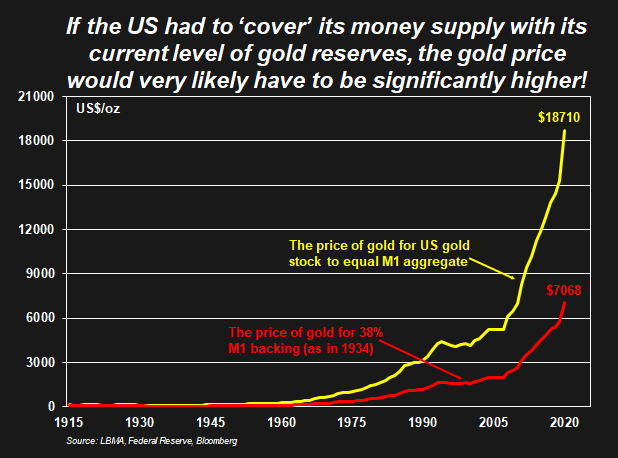

For example, Under the Gold Standard in 1934, to cover a ratio of 38% the US M1 money supply has been limited. Or, said another way, the value of gold held in reserves had to be at least 38% of the value of the currency in circulation.

The Price of Gold for 38% V/s The Price of Gold for US Gold Stock Chart

The Price of Gold for 38% V/s The Price of Gold for US Gold Stock Chart

The closure of the gold window on August 15, 1971 ended this arrangement; central banks could hold US dollars as they saw fit. However, the US was no longer going to convert those dollars for gold when asked to do so.

This was not a new phenomenon under a Gold Standard as countries have always, at the end of the day, refused to exchange gold for domestic currency. When it no longer suits them to do so, be they reserve-currency countries or otherwise.

In the 1930s countries left the gold standard as they needed to deflate their currencies. When high unemployment and/or negative growth became unbearable.

And, as we saw on August 15, 1971, the reserve-currency country will also exit from a gold-exchange standard. When it refuses to honor the promise that it will convert its currency for gold with foreign central banks.

The strains of the Bretton Wood system started to show in the 1960s. Persistent, albeit low-level, global inflation made the gold price low in real terms.

The Demise of the Gold Standard

A chronic US trade deficit drained US gold reserves. But there was considerable resistance to the idea of devaluing the dollar against gold. In any event, this would have required agreement among surplus countries. To raise their exchange rates against the dollar to bring about the needed adjustment (World Gold Council).

The fundamental reason for the demise of the Gold Standard and the Gold-Exchange Standard is straightforward. Both are fixed exchange rate systems.

In the Bretton Woods System, the US dollar was fixed at $35/oz. to gold. The other currencies were fixed to the US dollar (with a band of +/-1% around the fix). To ensure the fix is maintained, But a fixed exchange rate system requires that every country applies appropriate policies to ensure the fix is maintained.

And that is the vulnerability of a fixed exchange rate system; it is inevitable that some form of economic disequilibrium will develop in the global economy; (i.e., as the result of the rise of China or the introduction of the euro).

Unpopular economic policies are required to preserve the fixed exchange rate system when disequilibrium occurs.

The signal of economic disequilibrium in a fixed exchange rate system is heavy foreign exchange market speculation against a currency.

Driving such speculation to include factors such as chronic current account deficits, declining foreign exchange reserves. Also, high rates of inflation, recessions, large budget deficits and high unemployment rates.

Whatever the specific factors, however, market speculation that the currency in question will have to be devalued (that its fix will have to be lowered) is the signal that there is disequilibrium in the system.

There was disequilibrium prior to August 15, 1971. Speculators increasingly convinced about the devaluation of the US dollar. And were accordingly going long gold, Deutschmarks, and yen.

The US asked Germany and Japan to raise the (fixed) value of their currencies against the dollar. Also, imposed capital controls to stop the flow of dollar investments to Europe. (The flow of dollars ended up in European central bank reserves. Under the rules of the gold exchange standard risked being converted into US gold).

Germany and Japan refused to revalue their currencies and the US refused to devalue the dollar against gold. (arguing that this the dollar/gold cross was the lynchpin of the whole system).

August 15, 1971 was the result – the US refused to exchange any more dollars for gold (it had essentially refused to do so since the late 1960s. After France converted most of its dollar holdings for gold). And the US imposed a 10% US import tariff. On all goods coming into the US (principally to induce the necessary currency revaluation abroad).

Since 1971 currencies have been floating against the dollar to a greater or lesser degree. Greater in the case of the Canadian dollar and lesser in the case of the Chinese renminbi.

Given however that dollar reserves have risen sharply since 1971, the reader can surmise. That most countries have continued the practice of deliberately keeping their currencies undervalued against the dollar.

There were various attempts in Europe to limit inter-regional currency fluctuations after August 15, 1971. These culminated with the introduction of the euro in 1999.

The euro system is a fixed exchange rate system within Europe. Indeed, the euro now too suffers from all the problems endemic to a fixed exchange rate system. (which have been solved through large loans between countries and further reaches into fiscal agreements between countries).

The Gold Standard of pre-1930s and the Gold-Exchange Standard that ended in 1971 failed to be the discipline. That governments require to do what they do not want to do. At least not when employment, welfare, and economic growth became more important policy objectives than the exchange rate.

When discipline was required (i.e. action was taken to arrest gold outflows. Including tighter monetary policies and more fiscal policy restraint. Also when these actions could then quite naturally lead to deflation, lower wages, higher unemployment, and recession) countries left the gold standard and devalued instead.

This leaves questions to ponder, such as, what role can gold serve in the international financial system? And why do central banks continue to increase their gold reserves?

Buy gold coins and bars and store them in the safest vaults in Switzerland, London or Singapore with GoldCore.

Learn why Switzerland remains a safe-haven jurisdiction for owning precious metals. Access Our Most Popular Guide, the Essential Guide to Storing Gold in Switzerland here