In thinking about the 2020s, I often find myself looking back to the 1920s. That decade began with a deep recession/depression and ended with a stock market crash. While we now see the 1920s as a kind of “in between” period, people at the time didn’t know another depression and war were coming. They looked forward to good things and often embraced risk—hence the “Roaring Twenties” label.

Ernest Hemingway spent part of the 1920s as an American journalist in Europe. His novel The Sun Also Rises is based partly on that experience. The book has a line that’s now a familiar quote: “How did you go bankrupt? Two ways: Gradually and then suddenly.”

That quote’s context is even more illuminating. It involves two friends talking about their financial problems.

I think this passage captures how debt often goes wrong. Mike had a good life but he thought he had more friends than he really did. Their friendship proved false, or at least superficial. And Mike also had creditors to whom he owed money, and who eventually ended his good times.

Our US federal debt situation has a similar tension. We have friends and resources. We are clearly the wealthiest nation on earth. Some fabulous things are happening, even if you don’t hear about them. Yet because our friends and resources aren’t as deep as we may think, we are gradually slipping closer to a giant bankruptcy.

In these letters about debt, I’ve mentioned economists Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff several times. A quick search says that I've mentioned them 59 times in my letters, first about their 2008 paper on debt and then in their magisterial 2011 book This Time Is Different which shows how these situations aren’t historically unusual. I wrote about it extensively at the time and even interviewed them for my own book Endgame.

Among other things, Reinhart and Rogoff talk about how a country’s debt crisis usually hits suddenly, in what they call a “Bang!” moment that forces previously unthinkable changes. Today I want to explore this process a little deeper, and also look at why Japan’s seeming ability to avoid a Bang! moment shouldn’t give us much comfort.

“The Fickle Nature of Confidence”

In This Time Is Different, Reinhart and Rogoff systematically catalog more than 250 financial crises in 66 countries over 800 years, looking for differences and similarities. A common thread in all these times and places: People thought their situation was different. They truly believed the old rules no longer applied. This confidence is usually wrong and leads to disaster—the Bang! moment.

The following is a passage from a November 2011 letter in which I mostly talked about a then-unfolding European debt crisis. It’s worth reading again to see how it now fits our US situation. (Please note, Rogoff and Reinhart are not conservative Austrian economists. I find no politics in their writing, just facts. Which are ugly things.) Quoting:

One of the most important sections of Endgame is in a chapter where I review (and compare with other research) the book This Time Is Different by Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff, and include part of an interview I did with them. This chapter was one of real economic epiphanies for me. Their data confirms other research about how things seemingly bounce along, and then the end comes seemingly all at once. Which we’ll term the Bang! moment. Let’s review a few paragraphs from the book, starting with quotes from the interview I did:

“KENNETH ROGOFF: It’s external debt that you owe to foreigners that is particularly an issue. Where the private debt so often, especially for emerging markets, but it could well happen in Europe today, where a lot of the private debt ends up getting assumed by the government and you say, but the government doesn’t guarantee private debts, well no they don’t. We didn’t guarantee all the financial debt either before it happened, yet we do see that. I remember when I was first working on the 1980s Latin Debt Crisis and piecing together the data there on what was happening to public debt and what was happening to private debt, and I said, gosh the private debt is just shrinking and shrinking, isn’t that interesting. Then I found out that it was being “guaranteed” by the public sector, who were in fact assuming the debts to make it easier to default on.”

Now from Endgame:

“If there is one common theme to the vast range of crises we consider in this book, it is that excessive debt accumulation, whether it be by the government, banks, corporations, or consumers, often poses greater systemic risks than it seems during a boom. Infusions of cash can make a government look like it is providing greater growth to its economy than it really is.

“Private sector borrowing binges can inflate housing and stock prices far beyond their long-run sustainable levels, and make banks seem more stable and profitable than they really are. Such large-scale debt buildups pose risks because they make an economy vulnerable to crises of confidence, particularly when debt is short-term and needs to be constantly refinanced. Debt-fueled booms all too often provide false affirmation of a government’s policies, a financial institution’s ability to make outsized profits, or a country’s standard of living. Most of these booms end badly. Of course, debt instruments are crucial to all economies, ancient and modern, but balancing the risk and opportunities of debt is always a challenge, a challenge policy makers, investors, and ordinary citizens must never forget.”

And the following is key. Read it twice (at least!):

“Perhaps more than anything else, failure to recognize the precariousness and fickleness of confidence—especially in cases in which large short-term debts need to be rolled over continuously—is the key factor that gives rise to the this-time-is-different syndrome. Highly indebted governments, banks, or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an extended period, when Bang!—confidence collapses, lenders disappear, and a crisis hits.

“Economic theory tells us that it is precisely the fickle nature of confidence, including its dependence on the public’s expectation of future events, which makes it so difficult to predict the timing of debt crises. High debt levels lead, in many mathematical economics models, to “multiple equilibria” in which the debt level might be sustained—or might not be. Economists do not have a terribly good idea of what kinds of events shift confidence and of how to concretely assess confidence vulnerability. What one does see, again and again, in the history of financial crises is that when an accident is waiting to happen, it eventually does. When countries become too deeply indebted, they are headed for trouble. When debt-fueled asset price explosions seem too good to be true, they probably are. But the exact timing can be very difficult to guess, and a crisis that seems imminent can sometimes take years to ignite.”

(End 2011 quote)

Think about that last part along with my oft cited sandpile analogy. The nicely growing sandpile looks perfectly stable even as fingers of instability form. But as Reinhart and Rogoff say, “When an accident is waiting to happen, it eventually does.” These situations can go from stability to collapse in an instant.

Why do people not see this? The merrily growing sandpiles induce false confidence. In the current era, Japan is the seemingly solid sandpile others are misreading.

Back in the 1980s, Japan was an economic juggernaut. You remember the stories. The Imperial Gardens were theoretically worth more than California. Tokyo real estate was worth more than all of the US? That era ended quite badly, as they usually do, but what followed was even more interesting.

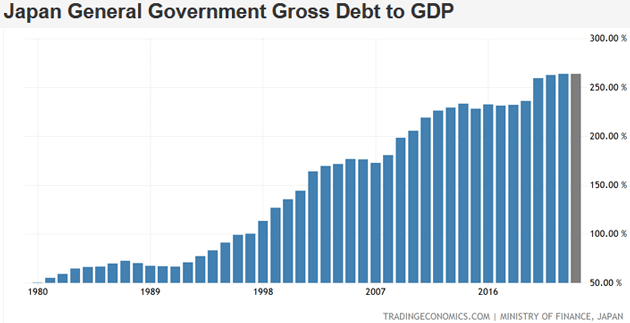

In the 1990s and early 2000s, successive Japanese governments and central bankers tried everything imaginable to kickstart growth. Nothing worked. Government debt grew to astonishing proportions. Even before the 2008 recession, Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio was already approaching 200%. A decade later it was over 250%. This is more than twice the equivalent US measure.

Source: Trading Economics

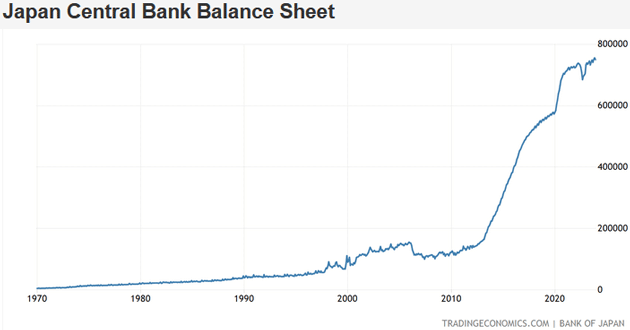

Then in 2012 the Bank of Japan tried what every textbook (and Rogoff and Reinhart) says is foolish: monetizing the government’s debt. This always causes inflation, but Japan actually wanted inflation. Constantly falling prices had produced economic stagnation.

The Bank of Japan bought every bond it could see and stocks, too, all while keeping interest rates at zero or below. Not just temporarily but for years. And for years, it seemed not to be working in terms of creating inflation. But it did allow massive government deficits which the BOJ bought. The main effect was to send the BOJ balance sheet to stratospheric heights.

Source: Trading Economics

Like what you’re reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

Subscribe for Free

Notice something in those two charts, though. Both the debt load and the BOJ balance sheet seem to be stabilizing in the last few years. They’re still at mind-bogglingly high levels but aren’t growing as fast. What happened?

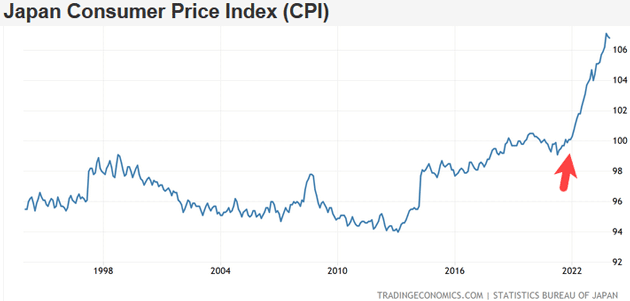

It now appears the combination of COVID supply chain snags and Ukraine war energy disruptions produced exactly what Japan wanted: inflation. Here is Japan’s CPI index for the last 30 years. This is the raw index, not annual change, so you can see exactly where the lift-off occurred.

Source: Trading Economics

To be clear, this is still less inflation than we’ve seen in the US since 2022. But relative to Japan’s recent experience, it’s almost unbelievable. And it’s having an effect. Rising input prices have forced Japanese businesses to raise prices, something many previously lacked the confidence to do. Those higher prices, combined with a serious labor shortage, are also beginning to raise wages and stimulate consumer confidence. It is still early, but this is starting to look like the much-fabled virtuous circle.

A policy victory? I don’t think so. To me it seems more like good luck. The pandemic and a faraway war set up exactly the conditions Japan needed. If Japan manages to avoid a Bang! moment (which is not yet certain as the yen approaches 150 to the dollar), it will have had a lot of help from external forces.

One might be tempted to look at Japan and think that surely the US, with its vastly greater power and resources, can manage a similarly safe exit. One thing I’ve learned in this business is to never say never. But in this case, I’d say the odds are lower than we might think. Not impossible, but low. The US isn’t Japan. I hope their solution works, for the sake of my friends and readers there. But that doesn’t mean it would work here.

I ran across this interesting analysis describing some of the important differences. To begin, the US has a large, structural trade deficit and current account deficit. Japan has the opposite. That means Japan-like policies here would have a much bigger effect on the dollar than the BOJ has had on the yen.

Similarly, the US is a net debtor nation. That’s not an accident; it is the flip side of our trade deficit and the petrodollar system. Japan is a net creditor, sending much of its enormous domestic savings overseas.

Japan’s government spending also looks quite different. While defense spending has increased recently (understandable when your neighbors include China and North Korea), it is still much less than the US. Ditto for healthcare, despite Japan’s rapidly aging population.

As a fiscal matter, Japan’s crazy debt-to-GDP ratio is more a function of stagnant GDP than out of control spending (though they have that too). Over the last decade, annual deficits ranged from 3.4% of GDP up to 8.7% in 2020’s COVID emergency.

It may be Japan’s lost decades weren’t actually “lost.” Maybe the passage of time was part of the solution, letting excesses be absorbed gradually. Patience pays off. Unfortunately, I don’t think we have that kind of patience in the US. We demand instant results and get grumpy when they don’t happen.

In terms of the US situation, I think the Japanese experience has two implications, both bad.

- Our debt can get a lot larger than it is now before a crisis hits, and

- The one precedent for a non-disastrous outcome probably won’t work here.

Let's unpack that. I’ve shown in past letters how the US government debt will likely exceed $60 trillion early in the next decade. That will mean over $2 trillion a year in interest payments alone, devastating any semblance of a viable budget.

What will stop us from doing what Japan did? Monetizing the debt to enormous levels? Truly creating the situation where we owe it to ourselves (or better stated, the Federal Reserve owes it to the US Treasury)?

I think it comes back to that concept of ephemeral, fickle confidence. Humans seem to think “this time is different.” And it is, until it isn’t.

Like what you’re reading?

Get this free newsletter in your inbox every Saturday! Read our privacy policy here.

Subscribe for Free

Japan had just one real crisis—too much private and government debt. Values collapsed, in real estate, stocks, and everything else. But what Japan didn’t have was a crisis of confidence in the value of their bonds. People trusted their bonds would eventually be repaid in terms real enough that there was no need to sell. In fact, they bought more! Just like we are doing in the US and Europe.

As we approach our own Bang! moment, which in my mind is somewhere towards the end of this decade or the beginning of the next, we will also face the four cyclical crisis I have been writing about over the last six months: Neil Howe’s Fourth Turning, Peter Turchin’s concept of elite overproduction, George Friedman’s geopolitical cycles which suggest war and rumors of wars, and Ray Dalio’s business cycle writings, all of which point to a crisis later this decade.

(Note: I did a summary last week (see here). It spurred the single largest reply volume in this letter’s 24-year history, mostly positive. I learn a lot from your comments and questions.)

These events, coupled with the dysfunctional political system, not to mention dysfunctional government, have a high probability of eroding the confidence that could produce a Japan-like solution for the US economy. Further, we have the real potential for another debt crisis to develop in Europe which would make US bond investors even more nervous.

I know I told you to read the following quote twice, but it really bears repeating one more time. This is critical to get into our minds as we approach what could be our Bang! moment.

“Economic theory tells us that it is precisely the fickle nature of confidence, including its dependence on the public’s expectation of future events, which makes it so difficult to predict the timing of debt crises. High debt levels lead, in many mathematical economics models, to “multiple equilibria” in which the debt level might be sustained—or might not be. Economists do not have a terribly good idea of what kinds of events shift confidence and of how to concretely assess confidence vulnerability. What one does see, again and again, in the history of financial crises is that when an accident is waiting to happen, it eventually does. When countries become too deeply indebted, they are headed for trouble. When debt-fueled asset price explosions seem too good to be true, they probably are. But the exact timing can be very difficult to guess, and a crisis that seems imminent can sometimes take years to ignite.”

That brings us right back to where I started this series. A debt crisis is coming to the world’s largest economy and issuer of the world’s reserve currency. The hundreds of examples Reinhart and Rogoff examined didn’t include anything approaching this global magnitude.

Maybe we’ll get through it with only mild disruption. The optimist in me hopes so. But the realist in me says any such hope is thin. Better to prepare for the Bang! moment.

New York, Somewhere in Florida, and…

I will be back in New York for one day this week, speaking at a private event for a friend. And then sometime in March I'm theoretically going to a follow-up meeting on the new biotech drug I mentioned last week.

This last week of travel was extraordinarily productive. I had dinner in Naples with my good friend Steve Cucchiaro and then lunch the next day with Pat Cox and Newt Gingrich. Then in DC had a dinner with libertarian writer and thinker John Tamny, a day-long, high-level meeting with Mike Roizen and a dozen doctors (most from Johns Hopkins) on a potential game changer in the healthcare space.

NYC had non-stop meetings. Sunday night was with uber-trader Michael Boyd and friends, the next day was lunch with major commercial real estate investor Yaniv Blumenfeld, then meetings with my publishing team and then we had dinner with David Bahnsen. Dalio Family Office CIO Mark Baumgartner was lunch amid other meetings and then a fabulous dinner with Peter Boockvar, Ben Hunt, Mauldin Economics partner Ed D’Agostino, Royalty Pharma founder (and Cibus chairman) Rory Riggs, and China Beige Book Managing Director Shehzad Qazi. China was a big discussion, as were lots of things, but AI dominated the conversation. (I do find interesting people for dinners!)

Then some of us went to Jared Dillian’s new book signing party. Jared's new book is No Worries: How to Live a Stress-Free Financial Life. The book shows readers how to become financially free without going to extremes. Just get a few big decisions right, and the rest will fall into place. A fun and easy read.

While the week of travel was very productive, it was also exhausting. My body doesn't travel as well as it used to. I need some of those new drugs available sooner.

With that, I will hit the send button. Have a great week! And don’t forget to follow me on X!

Your thinking about and needing new biotech analyst,

John Mauldin

P.S. If you like my letters, you'll love reading Over My Shoulder with serious economic analysis from my global network, at a surprisingly affordable price. Click here to learn more.